Having written last time about Victor Hugo I will add something here about his lover Léonie d'Aunet, a novelist and playwright who inspired many of the poems in Les Contemplations (1856). She was not merely a writer though, she was an Arctic explorer. Last year I mentioned the trip painter Emma Stibbons made to Svalbard, following in the footsteps of other artists who have taken part in the Cape Farewell voyages, but Léonie d'Aunet was the first woman ever to visit the archipelago. In 1838 she accompanied her future husband, painter François-Auguste Biard, on an expedition led by the scientist Joseph Paul Gaimard. Biard's painting above was acquired by the Louvre in 1841 and is subtitled 'view taken from the Tombs Peninsula, north of Spitsbergen; aurora borealis effect.' There were no casualties on their expedition, but the figures in the foreground prefigure later famous tragedies.

An article on a UN website talks about Léonie d'Aunet's published recollections in relation to climate change. She described setting foot on ground at Magdalena Bay:

“I said on the ground, as one usually does, but I should have said on snow, because I couldn’t see the slightest part of earth,” she wrote in her book Voyage d’une femme au Spitzberg (1854). Even in summer, everything was covered in snow and “between each mountain there are glaciers, which are growing in height every year. This is inevitable: the immense amount of snow that piles up during the 10-month winter cannot change in the summer that lasts only for some weeks. Eventually, in time the glaciers will be as high as the surrounding granite peaks.” The French woman’s predictions have, of course not materialised.

Now the landscape of Svalbard (Spitsbergen is its largest island) is at risk from global heating. 'An avalanche in 2015 cost two lives in Longyearbyen, the world’s northernmost permanent settlement. They were described as Svalbard’s first deaths from climate change.'

I am not sure if Leonet d'Aunet's book is properly available in an English translation, but there are some quotations from it in a 1903 anthology called Celebrated Women Travellers of the Nineteenth Century.

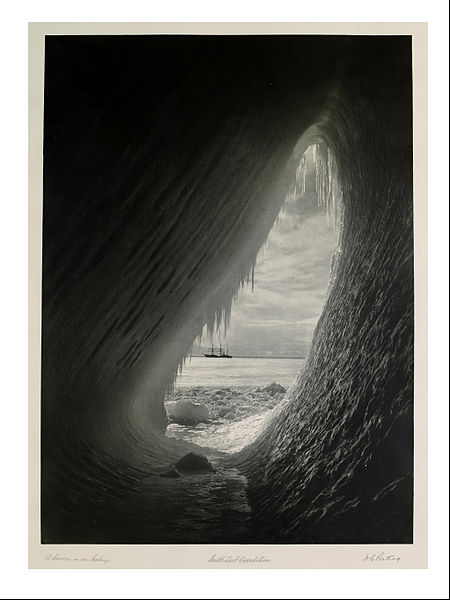

According to the UN article, 'Since the 1980s, the amount of summer sea ice has halved, and some scientists fear it will be gone altogether by 2035.'The ice-fields and the icebergs[Pg 130] inspired Madame d'Aunet with profound emotion, and, in describing them, she breaks out into what may be called a lyrical cry. "These Polar ices," she exclaims, "which no dust has ever stained, as spotless now as on the first day of the creation, are tinted with the vividest colours, so that they look like rocks composed of precious stones: the glitter of the diamond, the dazzling hues of the sapphire and the emerald, blend in an unknown and marvellous substance. Yonder floating islands, incessantly undermined by the sea, change their outline every moment; by an abrupt movement the base becomes the summit; a spire transforms itself into a mushroom; a column broadens out into a vast flat table, a tower is changed into a flight of steps; and all so rapidly and unexpectedly that, in spite of oneself, one dreams that some supernatural will presides over those sudden transformations. At the first glance I could not help thinking that I saw before me a city of the fays, destroyed at one fell blow by a superior power, and condemned to disappear without leaving a trace of its existence. Around me hustled fragments of the architecture of all periods and every style: campaniles, columns, minarets, ogives, pyramids, turrets, cupolas, crenelations, volutes, arcades, façades, colossal foundations, sculptures as delicate as those which festoon the shapely pillars of our cathedrals—all were massed together and confused in a common disaster. An ensemble so strange, so marvellous, the artist's brush is unable to reproduce, and the writer's words fail adequately to describe![Pg 131]

...

"The sea, bristling with jagged sheets of ice, clangs and clatters noisily; the lofty littoral peaks glide down to the shore, fall away, and plunge into the gulf of waters with an awful crash. The mountains are rent and splintered; the waves dash furiously against the granite capes; the icebergs, as they shiver into pieces, give vent to sharp reports like the rattle of musketry; the wind with a hoarse roar, scatters tornadoes of snow abroad.... It is terrible, it is magnificent; one seems to hear the chorus of the abysses of the old world preluding a new chaos."

.jpg/1920px-Eug%C3%A8ne_Delacroix_-_Ovide_chez_les_Scythes_(1862).jpg)

.jpg/800px-Blue_iceberg_(6141193525).jpg)

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/1280px-Pieter_Bruegel_the_Elder_-_Hunters_in_the_Snow_(Winter)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

_VMFA_83-46.jpg?uselang=en-gb)

%2C_1873.jpg/800px-Camille_Pissarro%2C_Gelee_blanche_(Hoarfrost)%2C_1873.jpg)