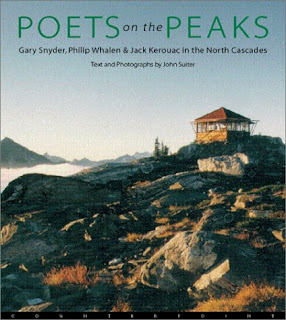

A book I never tire of dipping into (and always end up re-reading more than I intended) is John Suiter's Poets on the Peaks. It describes the experiences of Gary Snyder, Jack Kerouac and Philip Whalen in the North Cascades where they all worked as lookouts, watching for fires from the summits of Crater Mountain, Sourdough Mountain and Desolation Peak. It is a most beautiful book to read, thanks to Suiter's black and white photographs of the key sites and landscapes. Some of these can be seen at the Poets on the Peaks website, along with extracts from the text. The section there that quotes from the book's Epilog gives a sense of how brief and special this episode in American literary culture was: the isolated lookout cabins that gave these poets the chance to experience wild nature, hard work and solitude, along with space to cultivate their poetry and Buddhism, are mostly no longer used. 'Fittingly, the last two operational fire-watch cabins on the Upper Skagit today are Kerouac’s on Desolation and Snyder’s and Whalen’s on Sourdough.'

Here are three Poets on the Peaks links:

- An interview with John Suiter and Gary Snyder

- John Suiter interviewed by Michael Rothenberg

- A review from the Skagit River Journal

'As the light increased I discovered around me an ocean of mist, which by chance reached up exactly to the base of the tower, and shut out every vestige of the earth, while I was left floating on this fragment of the wreck of a world, on my carved plank, in cloudland... All around beneath me was spread for a hundred miles on every side, as far as the eye could reach, an undulating country of clouds, answering in the varied swell of its surface to the terrestrial world it veiled. It was such a country as we might see in dreams, with all the delights of paradise.'

- from "Tuesday" in A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers

.jpg/1280px-Song_Shan_(6169489672).jpg)