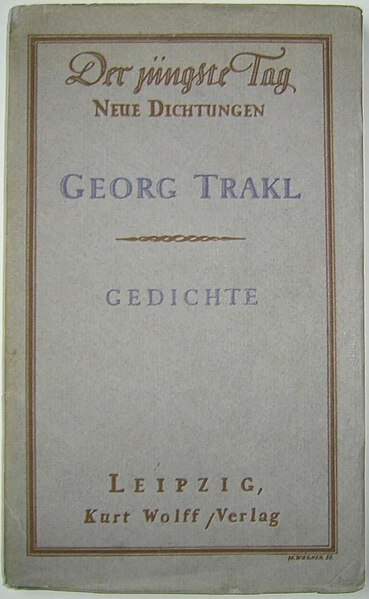

Heidegger thought that all of Georg Trakl's poetry was really one long poem, and perhaps it could be said that all of his poetry takes place in one landscape, with its and silent woods and dark paths, barren fields and withered gardens. Sometimes Trakl is content to create a poem almost entirely out of such images in parataxis; at other times they form a setting for the lonely wanderers that drift through his world like the figures in a Munch painting. It is quite easy to give a sense of this composite landscape through a selection of quotes. What I have done here is extracted a series of single line descriptions, each from a different poem in his first book, Gedichte, which was published in July 1913, less than 18 months before Trakl's death. The translations are by Margitt Lehbert.

From the earth decay is seeping.

Flies are buzzing in yellow vapours.

The reed’s small movement sinks and rises.

Pitch-black skies of sheeted metal.

Menacing blossom-claws in treetops.

Swallows sketch lunatic signs.

The pond’s mirror loudly shatters.

Through black branches, the toll of grievous bells.

The tilled field shines white and cold.

It is a stubble field on which a black rain falls.

Ice-cold winds moan in the dark.

An old man turns sadly in the wind.

It is an empty boat that drifts down the black canal in the evening.

The blackbird laments in leafless branches.

Franz Marc, Red Deer, 1913

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Trakl's work seems to lend itself to reworking as well as straight translation. An article in Jacket 2 describes two recent examples: Christopher Hawkey's 'writing through' Trakl in Ventrakl, and Daniele Pantano's reordering of lines from his verse in ORAKL. In addition to extracting landscape descriptions and turning poems into haiku, I have contemplated other operations such as arranging Trakl's lines according to colour. Simple colour adjectives are used in almost every poem. From his yellow suns, green forests, blue doves and white poppies it would be easy to assemble an expressionist painting resembling those of contemporaries like Franz Marc. The poems can be searched for one particular colour, noting for example Trakl's red leaves, red deer, fish, wine, dresses, money, breasts and clouds (this last occurs in his famous war poem, 'Grodek'). However, as my list above illustrates, Trakl's places are also haunted by blackness, and in the course of reading him you will encounter black decay, black snow, black wind, black waters, black silence.

But, rather than end this post in blackness, I will conclude by quoting some of Trakl's uses of the colour blue.

Blue asters in the wind bow low and shiver.

Your lips drink the cool of the blue rock-spring.

The blue river runs splendidly on...

The blue of springtime waves through snapping branches...

A glance of blue / breaks from crumbling cliffs

A blue animal wants to bow before death...

A blue gust of air played placidly through the old elder...

O to dwell in the soulful blue of night.