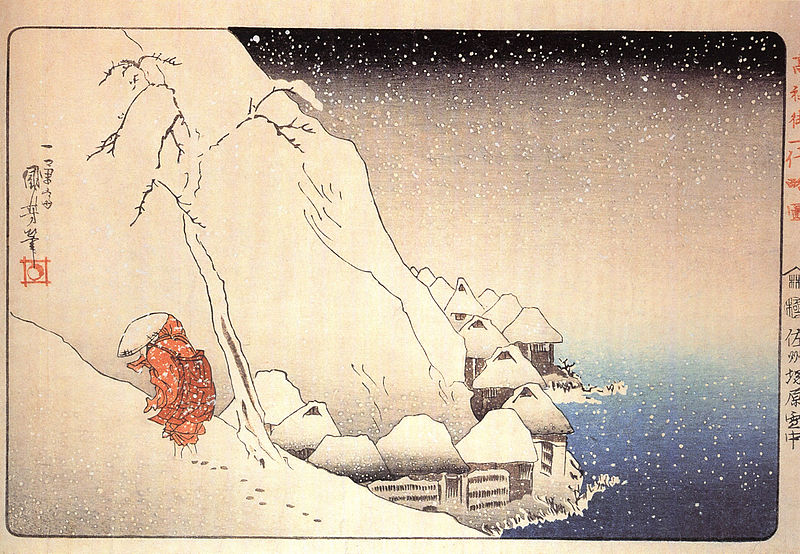

Determined now to rid ourselves of Netflix and save some money, we have started watching a few last films that we hadn't got round to before cancelling: last night it was Charlie Kaufman's I'm Thinking of Ending Things (2020). At some points in this, Jessie Buckley's character is a landscape painter (I won't spoil the story by explaining why I say "at some points"). There is an awkward conversation over dinner at the parental home of her boyfriend Jake (Jesse Plemons), where she tries to explain that she imbues landscapes with "interiority". David Thewlis, Jake's father, says he wouldn't understand a landscape to be sad unless there was a sad person in the painting looking at it. Elsewhere in the house there is a reproduction of Friedrich's Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818) - a man looking at a landscape, but one that is so obscured in mist that it may not even exist. Jake's father will descend (or has descended) into dementia, gradually forgetting everything. Plemons and Buckley spend a lot of the film surrounded by darkness and a blizzard of snow.

When Jessie Buckley pulls up some images of her paintings on her phone to show the parents, they are actually by Ralph Albert Blakelock (1847-1919) - later we see posters of his work in Jake's basement. Blakelock was a fairly obscure painter until late in life when his work began attracting attention and started selling for high prices. But he never got to enjoy the recognition - he had succumbed to mental illness in the 1890s and spent his last two decades in institutions suffering from schizophrenic delusions. There are echoes of this in I'm Thinking of Ending Things, with Jake's feelings of paranoia and the way he slips into an elaborate fantasy at the film's climax (winning the Nobel prize on the set of Oklahoma!)

This Blakelock painting in the Brooklyn Museum also features in Moon Palace, a novel by Paul Auster, whose work occupies a similar territory to Kaufman (I've been an admirer of Auster since New York Stories and was sad to read of his death in April). 'A perfectly round full moon sat in the middle of the canvas - the precise mathematical center, it seemed to me - and this pale white disc illuminated everything above it and below it: the sky, a lake, a large tree with spidery branches, and the low mountains on the horizon...' I won't quote the full ekphrasis, although you can find the extract on a website for German English teachers. Instead I'll end here with the moment Auster's protagonist starts to notice something odd about the painting.

The sky, for example, had a largely greenish cast. Tinged with the yellow borders of clouds, it swirled around the side of the large tree in a thickening flurry of brushstrokes, taking on a spiralling aspect, a vortex of celestial matter in deep space. How could the sky be green? I asked myself. It was the same color as the lake below it, and that was not possible. Except in the blackness of the blackest night, the sky and the earth are always different. Blakelock was clearly too deft a painter not to have known that. But if he hadn't been trying to represent an actual landscape, what had he been up to? I did my best to imagine it, but the greenness of the sky kept stopping me. A sky the same color as the earth, a night that looks like day, and all human forms dwarfed by the bigness of the scene - illegible shadows, the merest ideograms of life...

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/1280px-Pieter_Bruegel_the_Elder_-_Hunters_in_the_Snow_(Winter)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

.jpg/1200px-Liu_Bei_Visiting_Zhuge_Liang_by_Yosa_Buson_(Nomura_Art_Museum).jpg)

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/800px-Pieter_Bruegel_the_Elder_-_Hunters_in_the_Snow_(Winter)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)