Friday, July 11, 2025

Pasture (and a Some Landscapes email feed)

Sunday, December 08, 2024

The Rock of Montmajour with Pine Trees

In a conventional telling, Van Gogh’s life in Provence was brutally split, as his first ecstatic months ended in self-harm and hospitalisation. Here, the translation to Saint-Rémy is not a tragedy at all. You see how his style got ever more free there. A later room is filled with landscapes he painted around Saint-Rémy that teeter on total abstraction: in The Olive Trees, the earth erupts in waves like the sea, trees dance, and a cartoon cloud is so free from rules it could be by Picasso.

The 1889 drawing of olive trees above that I photographed in the exhibition shows just how abstract and decorative his work was becoming.

There is a whole room dedicated to one landscape series: drawings made in the vicinity of the ruined 12th-century Montmajour Abbey. The curators note that its 'terrain put the artist strongly in mind of the abandoned garden 'Le Paradou' (a Provençal word for 'Paradise'), which featured in Emile Zola's novel The Sin of Abbé Mouret (1875).' The sketch below is The Rock of Montmajour with Pine Trees (1888) and it 'includes an obscured glimpse of Arles on the far left. In Zola's novel, the Abbé, who has forgotten his vows of chastity due to amnesia, occupies the wild paradise of Le Paradou with his lover, distanced from the realities of everyday life.' After reading this I thought I would make an effort to read the novel and then do some more in depth comments here, but online reviews of it are not encouraging. A film adaptation by Georges Franju doesn't sound that enticing either. If I ever do get round to either of these I may add a postscript to this blog post.

Sunday, May 07, 2023

Atlantic Flowers

Last year I bought the latest New Arcadian Journal, Atlantic Flowers: The Naval Memorials of Little Sparta. 'The upland garden of Little Sparta is evocative of distant seas. Atlantic Flowers offers fresh insights into the poetic gardening of Ian Hamilton Finlay (1925-2006) by acknowledging that the warship sculptures are simultaneously naval memorials.' This makes it sound like quite a specialised study but the pleasure of reading the journal (essentially a beautifully illustrated book), is that it conveys a lifetime's engagement with the garden as a whole and Patrick Eyres' long friendship with Finlay. An appendix provides a bibliography of ten previous NAJs and eleven New Arcadian Broadsheets devoted to Little Sparta and IHF. Photographs show how garden features have evolved over time, since Patrick's first visit in 1979. Paintings, drawings and artworks are reproduced on almost every page, based on the work of Finlay and NAJ collaborators and friends like Chris Broughton, Catherine Aldred and former-Mekon Kevin Lycett.

The last artwork discussed in Atlantic Flowers was installed in 2001, not long before Finlay's death: Camouflaged Flowers. This was conceived as a monument to the men of the wartime Flower Class corvettes, ships that had been given incongruously pastoral names like Begonia, Larkspur and Heartsease. Some of them were transferred to the US Navy during the war and renamed; in 'Ovidian Flowers' Finlay highlighted these metamorphoses: Begonia became Impulse, Larkspur Fury and Heartsease Courage. Nicholas Monsarrat wrote about life on board a corvette in The Cruel Sea. In his memoir he described these boats as 'cramped, wet, noisy, crowded, and starkly uncomfortable.' They may have had lovely floral names but they were all the same: 'wallowing cages for eighty-eight men condemned to a world of shock, fatigue, crude violence and grinding anxiety' (It Was Cruel, 1970). Finlay's Camouflaged Flowers was the culmination of his interest in the Flower Class corvettes, following printed works, wall plaques and an obelisk. It consists of seven brick plinths with bronze plaques commemorating five ships: Lavender, Campion, Polyanthus, Montbretia and Bergamot. Three of these survived, two were torpedoed. Polyanthus sunk with total loss of life.

I'll conclude here with Patrick Eyres' description of Camouflaged Flowers, which Finlay located 'high on the hillside at the edge of moorland, where they are exposed to wind and the vagaries of weather.'

'Here this monumental artwork is an epic composition that embraces the 'disparate elements' of garden and landscape, planting and sculpture, weather and seasons, and which is animated by leaf, blossom and berries. Now that it has matured, we can appreciate that the moorland swell and undulating horizon are evocative of Atlantic seascapes. The plantings can be imagined as the waves, through which the corvettes plough their way. Sea states are intimated by the foreground grasses, whether windblown or swaying in the breeze.'

Sunday, September 04, 2022

Taming the Garden

MUBI was a godsend during Covid lockdowns and is still proving good value for money as far as we're concerned. This week I watched Taming the Garden by Salomé Jashi, a documentary with extraordinary images of moving trees. 'Georgia’s former prime minister [Bidzina Ivanishvili] has found a unique hobby. He collects century-old trees, some as tall as 15-floor buildings, from communities along the Georgian coast. At a great expense and inconvenience, these ancient giants are uprooted from their lands to be transplanted in his private garden.' Peter Bradshaw's review in The Guardian mentions some of the obvious references that spring to mind as you watch it (Macbeth, Fitzcarraldo) and describes Jashi's unobtrusively filmed footage of people involved in moving the trees:

Local workers squabble among themselves at the dangerous, strenuous, but nonetheless lucrative job of digging them up. The landowners and communities brood on the sizeable sums of money they are getting paid and Ivanishvili’s promises that roads will also be built. But at the moment of truth, they are desolate when the Faustian bargain must be settled and the huge, ugly haulage trucks come to take their trees away in giant “pots” of earth, as if part of their natural soul is being confiscated.

I am reminded of a previous blog post I wrote on the creation of Song Emperor Hui-tsung's garden, where plants and rocks were shipped in from all over China, and its later fictionalisation in Ming dynasty novel The Plum in the Golden Vase, which tells the story of a licentious and corrupt character called Hsi-men Ch’ing.

Resentment has built up during its construction, as the process of shipping 'so many huge rocks and plants had cluttered up the canals and transport system. There had also been endless corruption and compulsion during the entire high-speed plan'. Unsurprisingly Hsi-men Ch’ing got involved in this. At one point in the novel he discusses with an official the way the 'flower and rock convoys' had impoverished ordinary people, before inviting him to partake of a typically lavish lunch.

Salomé Jashi's slow, beautifully-shot documentary has no Herzogian narrator or any explanation of what is happening - the actual scale of the exercise, its costs, its purpose, its outcomes. Another Guardian piece by Claire Armistead makes the point that 'Taming the Garden is far from a balanced two-minute news report; it stands at the junction of documentary and myth, not even mentioning that Ivanishvili’s garden is now open to the public.' A New York Times article by Ivan Nechepurenko notes that the Shekvetili Dendrological Park opened in 2020, 'but signs declaring this property private are everywhere. CCTV cameras are installed throughout, and motion detectors stand in front of every tree. Look, but don’t dare touch. And that message goes for the lawn, too. Guards with loudspeakers are quick to scold the noncompliant.' He describes Ivanishvili's political background and links to Russia, where he acquired his vast wealth from metals and banking. He also includes reflections from an academic researching the interconnectedness of trees and their supporting fungal networks, who says she felt physical pain when she heard about the project.

The trailer for Taming the Garden embedded above includes some of Jashi's poetic compositions, including lovely details like drifting steam and water running over metal. As Claire Armistead writes, 'although many trees were involved in the filming,

their stories are represented by one symbolic journey.' She goes on to pick out a few details:

Villagers gather with their bicycles to see the tree on its way. A man lights his first cigarette in 30 years. An elderly woman weeps and convulsively crosses herself, while her younger relatives excitedly record the removal on their phones. As the tree is sailed along the coast – in a repeat of the image that inspired the film – two bulldozers await it on a stone mole, their excavator arms lowered like bowed heads at a funeral. And in a rich man’s manicured garden, round the half-buried roots of ancient trees held upright by guy ropes, the sprinklers come on.

Sunday, May 30, 2021

Knowing the East

Paul Claudel (1868 - 1955) joined the French Ministry for Foreign Affairs after university, where he had begun writing poetry and attending Mallarmé's 'Tuesdays', and in 1895 was made vice-consul in Shanghai, following junior postings in Boston and New York. He would spend the rest of his life as a prominent diplomat and writer, although I suspect that in England he is a lot less well known than his sister Camille (portrayed in the 1988 film Camille Claudel by Isabelle Adjani). When he arrived in the Far East he began composing prose poetry; the first one was written in Ceylon before he reached his destination in China. Some of these poems were sent home and published in outlets lke La Revue de Paris and La Revue blanche. Claudel returned in 1899 intending to become a priest, and his book Connaisance de l'Est came out in 1900. But having abandoned his religious vocation and returned to China, he supplemented this volume with a smaller group of poems written in the period up to 1905.

No doubt Knowing the East can be read critically in terms of Orientalism and French imperialism, but I found a lot of beauty in these poems. Some titles: 'The City at Night', 'Sea Thoughts', 'The Sadness of Water', 'Noon Tide', 'Hours in the Garden', 'Libation to the Coming Day'. Things I was reminded of as I read them: Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Francis Ponge, Lafdacio Hearn, Victor Segalen, Empire of Signs, Invisible Cities. This quote, from their translator James Lawler, summarises my first impressions of the book.

'With what pleasure do we savour these landscapes, this continent so far removed from our own: coconut palms, banyans, Japanese pines; the Yang-tse of 'Drifting', 'The River', 'Halt on the Canal'; Confucian, Buddhist, and Shinto temples and tombs; hermitages, suspended houses; crushing heat, night as clear as day; festivals for the dead, a festival for the rivers; wheat harvests, rice harvests; torrential rain, apocalyptic storms; cities that seem chaotic but have a concealed pattern and sense, 'flayed' Chinese gardens, the Shogun's golden ark. One may label the images picturesque but that is not the way I read them. I recall Julien Green saying of Claudel that he was a man "who had known how to live elsewhere," words I take to mean that we do not find a quest for oddness but affectionate deployment fold by fold of a reality the poet comes to know.'

In keeping with the theme of my blog, here are a few examples of how Claudel treats landscape in his poems:

- Stopping to survey the mountains that surround him, he measures with his eyes the route he will take. As he walks, he savours the slow passage of time and thinks about 'the bridge still to cross in the quiet peace of the afternoon pause, these hills to go up and down, this valley to traverse.' He already sees the rock where he will watch the sunset.

- One December day, 'a dark cloud covers the entire sky and fills the mountain's irregular clefts with haze: you would think it dovetailed to the horizon.' He sweeps the quiet countryside with his hand, caressing the hyacinth plains, the tufts of black pines, and he checks with his fingers the 'details embedded in the weft and mist of this winter day - a row of trees, a village.'

- On the vast yellow river he thinks about the nature of water. 'As the segments of a parallelogram come together and meet, so water expresses the force of a landscape reduced to its geometrical lines.' Each drop expresses this as it finds the lowest point of a given area. 'All water draws us, and certainly this river...'

- He describes knocking on a small black door somewhere in Shanghai and being led through a succession of corridors to a garden. He follows a labyrinthine path until he can look down on 'the poem of the roofs'. Later he reaches 'the edge of the pond, where the stems of dead lotus flowers emerge from the still waters. The silence is deep like that of a forest crossroads in winter.'

- And in a Tokyo shop, he finds himself looking at miniature landscapes (bonkei). 'Here is the rice field in spring; in the distance, the hill fringed with trees (they are moss). Here is the sea with its archipelagos and capes; by the artifice of two stones, one black, the other red and seemingly worn and porous ... Even the iridescence of the many-coloured waters is captured by this bed of motley pebbles covered by the contents of two carafes.'

Saturday, July 18, 2020

The Garden of Eusebius

Eusebius: 'Now that the whole countryside is fresh and smiling, I marvel at people who take pleasure in smoky cities.'

Timothy: 'Some people don’t enjoy the sight of flowers or verdant meadows or fountains or streams; or if they do, something else pleases them more. Thus pleasure succeeds pleasure, as nail drives out nail.'

This exchange can be found in The Godly Feast, one of the Colloquies written by Erasmus (first published in 1518 and then added to over the years; the Craig R. Thompson translation is available at the Catena Archive). Erasmus has Eusebius argue that "nature is not silent but speaks to us everywhere and teaches the observant man many things if she finds him attentive and receptive." To prove his point he suggests a visit to his "little country place near town, a modest but well-cultivated place, to which I invite you for lunch tomorrow." Timothy is worried he and his friends will be putting Eusebius out, but Eusebius reassures him: "you’ll have a wholly green feast made, as Horace says, 'from food not bought.'"

When they meet at this villa, Eusebius shows Timothy his statue of Jesus at the entrance to the garden: "I’ve placed him here, instead of the filthy Priapus as protector not only of my garden but of everything I own; in short, of body and soul alike." Eusebius stresses the utility and lack of luxury in his garden. What appears to be marble is merely painted concrete - ''we make up for lack of wealth by ingenuity". There is a lesson for life in this: appearances can be deceptive, he warns Timothy. A delightful stream is not all it seems either. It is used to drain kitchen waste to the sewer, like Sacred Scripture cleansing the soul. Elsewhere there are herbs for cooking and medicine, exotic trees, an aviary, orchards and bee hives.

In addition to the garden itself, Eusebius has had frescoes painted showing views of nature. This second, painted world even extends beneath their feet: "the very ground is green, for the paving stones are beautifully colored and gladden one with painted flowers". He explains to Timothy that:

"One garden wasn’t enough to hold all kinds of plants. Moreover, we are twice pleased when we see a painted flower competing with a real one. In one we admire the cleverness of Nature, in the other the inventiveness of the painter; in each the goodness of God, who gives all these things for our use and is equally wonderful and kind in everything. Finally, a garden isn’t always green nor flowers always blooming. This garden grows and pleases even in midwinter."Eusebius is proud of his garden but he is just as keen to mention his library, globe and paintings. I like the fact that place names have been added to his religious paintings, "to enable the spectator to learn by which water or on which mountain the event took place". It is clearly the ideal of a Renaissance scholar, and the garden is a highly artificial landscape. Indeed, John Dixon Hunt has pointed out that it is 'substantially architectural: walled, with galleries and pillars, it may be seen as much as a city as a garden.'

Wednesday, January 29, 2020

Water, the unsteady element

Goethe's novel Elective Affinities (1809) is about attraction and marriage, duty and freedom, centring on an analogy with the way certain chemicals combine with others. It is also about landscape design - something barely mentioned in Walter Benjamin's much-admired essay on the book, but clearly influential on Tom Stoppard, whose play Arcadia, a re-writing of Elective Affinities, foregrounds this theme. Goethe's story begins with a rich married couple, Eduard and Charlotte, gardening for pleasure on their large estate. The first of the two characters whose arrival disrupts their marriage, Eduard's old friend The Captain, is given the job of surveying this land and making improvements. He undoes some of Charlotte's work, suggesting changes to a rocky path she made that would create instead a sweeping curve. Their constant companionship eventually turns to love and meanwhile Eduard is himself falling for Ottilie, the young girl - his daughter's contemporary - who comes to stay with them. He has a new house has built in an ideal spot with a fine prospect over the landscape, and it seems as if he has built it for her.

In the introduction to his translation, David Constantine describes the characters' focus on gardening. 'Though the style aimed at is English and so, by comparison with the French, informal, this is only the studied informality achieved also in the village when the villagers, spruced up for Sundays, gather before their cottages in 'natural' family groups. The principal impulse in the garden is still to control, arrange and tame.' The novel, particularly in its later stages, is haunted by death. And 'although in real life there may be nothing particularly wrong (at least nothing deserving of death) in landscape gardening,' this and other examples of controlling behaviour suggest a society set against change or any way for the characters to escape their roles. The most ambitious landscaping project involves the merging of three ponds and in a celebration to mark this event, a boy is nearly drowned. At the end of the book, Ottilie accidentally drowns Charlotte's baby in these same waters.

'Ironically, by merging the ponds they were returning them to their former and in that sense more natural state; for they were once, as the captain has found out, a mountain lake. Nature, especially water, 'the unsteady element', constitutes a threat throughout the novel; or we might say, it is present as an alternative to the rigidity of the estate. That alternative, the way of greater naturalness, appears as a threat, and in the end as a deadly threat, to people afraid to embrace it.'

Friday, January 24, 2020

Goethe's oak

I was on something of a Goethe pilgrimage last weekend, with five stops, beginning in his childhood home in Frankfurt. This was where he began Faust and wrote Werther before moving to Weimar at the age of twenty-six. The house itself was destroyed in an Allied bombing raid but has been reconstructed; the contents were all kept safe during the war. What you see when you look round is essentially the home Goethe's father created, including his pictures - some of them landscapes - all framed in black and gold. I particularly liked two circular landscape views in the music room either side of a pyramid piano. There is no readily accessible information on who painted these, which is a pity because I would love to know more. The website refers to paintings 'in the Dutch tradition (Trautmann, Schütz the Elder, Juncker, Hirt, Nothnagel, Morgenstern), and by the Darmstadt court painter Seekatz'. Schütz the Elder was a landscape specialist, so perhaps they are by him.

Goethe returned to this garden house near the end of his life to work on the Italian Journey (this account of his travels in 1786 has always been one of my favourite books, in the classic translation by W. H. Auden and Elizabeth Mayer). To help remember the topography of Rome he had two large panoramas of the city put up in the dining room. The print I photographed below is Giuseppe Vasi’s view of modern Rome as seen from the Janiculum Hill (1765). Turn round and on the opposite wall you see Pirro Ligorio’s bird’s-eye view of ancient Rome, originally published in 1561.

The drawing below by Goethe below looks at first sight like a view of cliffs, but is actually a Hypothetical Depiction of a Mountain. It is a good example of his interest in morphology and archetypal structures. Goethe had a professional interest in geology through his involvement in mining, but it was evidently an absolute passion for him. His geological collection eventually numbered 18,000 items. I loved this quote about his collection of tin specimens:

'For many years, especially after 1813, Goethe was occupied by stannous (tin) rock formations. He collected them in Bohemia and Saxony and had them sent to him from all over Europe. He called it his "tin pleasure". He considered tin to be the primeval metal, as it marked the end of the granite age. Despite years of study, he only published one short article on the subject of tin.'

Goethe died in 1832. Just a century later the Nazis were on the verge of power and five years on they were constructing a concentration camp on the beautiful wooded hill overlooking Weimar. The camp was originally going to be called Ettensburg, but because this place name had such strong associations with Goethe and enlightenment, it was decided to use the name Buchenwald, 'Beech Wood'. Trees were cleared for the building of the camp, but one oak tree was left standing. The inmates began to call it Goethe's oak, a living symbol of a better Germany. The tree was damaged by bombing in 1944 and then felled, but its base has been preserved as part of the Buchenwald memorial. You can see it in my photograph below under last weekend's grey winter sky. The dark shape among the trees behind it is the tower of the crematorium.Goethe's Hypothetical Depiction of a Mountain (probably 1824)

Saturday, December 21, 2019

Hanging Gardens of Rock City

In the British Museum at the moment you can see Hanging Gardens of Rock City, a collage by Liliane Lijn. It was one of four she made in 1970, imagining aerial walkways and parks among the rooftops of Manhattan. Of course these can now be seen as anticipating The High Line. The museum caption quotes her as saying 'I have always found the rooftops of the buildings in Manhattan exciting and strange as if their architects had allowed their fantasies free at that distance from the ground.' In her collages, the public has access to these private buildings and can be seen sunbathing and walking around, far above the streets of the city.

In the sixties Lijn moved from New York to London, where she was married to Takis, who was the subject of a major retrospective at Tate Modern earlier this year. In the course of her long career she has worked in all media, from performance to prose-poems and made plastic sculptures, poem machines, 'vibrographs', cone-shaped koans, kinetic clothing, light columns, biomorphic goddesses and solar installations in the landscape. The last of these is of particular interest here. They are collaborations with astronomer John Vallerga in which powerful prisms reflect sunlight of different colours, depending on their angle. Getting permission to install these has not been easy and ensuring they are protected from damage is also a challenge. The video below shows a couple of these artifical suns on the hills behind the Golden Gate Bridge. Another, Sunstar, has been shining from the summit of Mount Wilson - the Los Angeles Magazine reported on it last year. Here is some information from the Mount Wilson Observatory website.

'An array of six prisms, Sunstar takes incoming sunlight and refracts it, bending the light and spreading it into a spectrum–all the colors of the rainbow. It is mounted near the top of the Observatory’s 150-foot Solar Telescope Tower. With motion controls, it can be remotely directed to project the spectrum to a specific point in the Los Angeles basin. An observer below will see an intense point of light in a single wavelength, shining like a brilliant jewel from the ridgeline of Mount Wilson, 5800 feet above in the San Gabriel Mountains. [...]

The prism will be beaming daily to various sites around the Los Angeles basin — Griffith Observatory, the Rose Bowl, Pasadena City Hall, Memorial Park by the Armory, Elysian Park, the Music Center, wherever there is a view of Mount Wilson. If you see it, please let us know what you think. Requests to have it beam your way can often be accommodated. Email: concerts@mtwilson.edu. Include the time you’d like to see the beam and your location’s address, or geographic coordinates if you prefer.'

Friday, November 08, 2019

Vaux-le-Vicomte

Last month we visited the Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte, just outside Paris. It was the home of Nicolas Fouquet, Louis XIV's finance minister, and was the creation of three great seventeenth century artists: architect Louis Le Vau, painter Charles Le Brun and landscape designer André le Nôtre. Throughout Vaux-le-Vicomte there are explanatory signs with diagrams explaining how le Nôtre constructed the estate to create optical illusions. When you look out from the house across the garden (below), you can see a distant slope with a golden statue, but there is no sign of the garden's canal (above) which actually stretches right across the garden. A sign informs visitors of what they can expect as they walk down into this landscape. "The Grand Canal, invisible from the château's front steps, appears out of the blue. The grottos, which seem to be on the pool's edge, get further away as you progress along the main path of the garden and now seem to be on the opposite side of the canal! The statue of Hercules now seems impossible to reach..." I think this clever example of 'decelerated perspective' put Mrs Plinius off walking as far as the Hercules statue but, as you can see below, I was not discouraged and went up to get a good look at it.

The sun was so strong that Hercules himself presented two very different perspectives, shadowy on the way up and gleaming magnificently when you looked back down at him. Although I felt like I was dutifully walking along a sightline, one of those rays on a diagram connected to an imaginary eyeball, it was impossible not to be distracted by birdsong and the crunch of fallen leaves under your feet. The sharp shadows and bright sunshine were perfect conditions to enjoy the garden's mathematical aesthetic and indulge in the scopophilia of all those viewing points. But it was still possible to enjoy the feel of the breeze and smell of the damp grass and choose your own ways of experiencing the space. My sons got caught up in a game of catching the falling leaves.

On the way back to the château, as you round one end of the canal, there is a great example of borrowed scenery (what Japanese gardeners call shakkei). What you can see (below) is the Vallée de l'Anqueuil and medieval Pont de Mons, giving the impression that Fouquet's land extended into this idyllic unspoilt landscape. Here, nature is incorporated within the realm of the garden, but this seems relatively modest when compared to the main design where (as Allen S. Weiss has written) infinity itself, in the form of the vanishing point, is brought into the garden's purview.

Sunday, May 12, 2019

The Garden or Evening Mists

Tan Twan Eng's The Garden of Evening Mists is a novel that circles round various mysteries: the life and death of a Japanese garden designer, Aritomo, living after the war in exile in Malaya, and the location and purpose of a prison camp that he may have had some connection with. The narrator of the novel, Yun Ling, a survivor of this camp, wants to create a garden in memory of her sister, who died there. This sister had developed a fascination with Japanese gardens on a visit to Kyoto before the war. Yun Ling goes to visit Aritomo, with the intention of asking him to design a memorial garden, but instead she becomes his apprentice, lover and then the inheritor of his own garden. Aritomo begins her training with a copy of the Sakuteiki (which I mentioned here once before), written by Tachibana no Toshitsuna in the eleventh century, and explains to her various principles of Japanese gardening, such as shakkei ('borrowed scenery'). Later she writes that 'Aritomo could never resist employing the principles of Borrowed Scenery in everything he did' and the reader suspects something significant in this, that the landscape beyond the garden has some kind of special significance linked to their memories.

When Aritomo first explains shakkei to Yun Ling, he mentions Tenryuji, "Temple of the Sky Dragon, the first garden to ever use the techniques of shakkei." Here's what I said about this garden, designed by the great poet Musō Soseki (1275-1351), in another earlier post:

'The temple of Tenryū-ji, was built by the shogun Ashikaga Takauji in memory of the emperor whom he had deposed. Musō wrote a sequence of poems about the landscape garden he helped create there, 'Ten Scenes in the Dragon of Heaven Temple.' Some of these scenes have survived the centuries, like the lake Sōgen-chi where moonlight still strikes the waters in the dead of night; others have gone, like Dragon-Gate House where Musō observed the most transient of images, two passing puffs of cloud.'Aritomo goes on to list the four approaches to shakkei: "Enshaku - distant borrowing - took in the mountains and the hills; Rinshaku used the features from a neighbour's property; Fushaku took from the terrain; and Gyoshaku brought in the clouds, the wind and the rain." Years later, looking again at their garden, Yun Ling wonders whether the wind and clouds and ever changing light had been part of Aritomo's design. And if the mists were an element of shakkei too, gradually thickening and erasing the distant mountains.

Friday, January 25, 2019

I made those waters flow over it

I am returning here to a subject I covered over ten years ago, the gardens of the kings of Assyria, because I have been to see the British Museum's exhibition, 'I am Ashurbanipal'. I ended my previous post by referring to a relief dated 645 which shows King Ashurbanipal and his Queen in the royal park in Nineveh, dining under an arbour of grape vines, with the decapitated head of the conquered king of the Elamites hanging from a nearby tree. This scene is on show in the current exhibition, mounted with other smaller ones to show how a complete wall might have looked. You can see this in my photograph above, which I think also gives an indicates of how wonderfully well lit everything is. The garden landscape in which Ashurbanipal is seen drinking and listening to music contains alternating pine and fruit-bearing date palms, perhaps symbols of Assyria and Babylonia respectively. And in the foliage, a bird goes after a locust - in his annals, Ashurbanipal likened the Elamites to a swarm of locusts.

This second photograph shows the royal park created by Ashurbanipal's grandfather Sennacherib, which I also mentioned in my earlier post. In the new exhibition, coloured light is projected onto this relief, picking out the irrigation channels and trees. You can see the effect in a gif at the British Museum blog site. I will quote here what this site has to say about the landscape:

'The gardens at Nineveh were irrigated by an immense canal network built by Ashurbanipal’s grandfather, Sennacherib. He brought water to the city over a great distance using channels and aqueducts to create a year-round oasis of all types of flora. The canals stretched over 50km into the mountains, and Sennacherib boasted about the engineering technology he used. A monumental aqueduct crossing the valley at Jewan, which you can still see the remains of today, was made of over 2 million stones and waterproof cement. The aqueduct was constructed over 500 years before the Romans started building their aqueducts, and was inscribed with the following words: "Sennacherib king of the world king of Assyria. Over a great distance I had a watercourse directed to the environs of Nineveh, joining together the waters… Over steep-sided valleys I spanned an aqueduct of white limestone blocks, I made those waters flow over it."Since I wrote my last blog post on the gardens at Nineveh, it has been argued that they were in fact 'the real Hanging Gardens of Babylon'. Archaeologist Stephanie Dalley first formulated this theory in 1992 and then published a book with new research in 2013. A Channel 4 documentary was made and her new evidence was widely reported in the news. It would obviously be helpful to do some more digging, but the site of Nineveh, around Mosul, has been too dangerous to excavate. Dalley was quoted in 2013 as saying she thought it unlikely that excavations would be possible in her lifetime. A year later, Daesh overran the area and, as Jonathan Jones says in his review of this exhibition, 'they smashed antiquities in the Mosul Museum and set about demolishing Nineveh itself.' It is sad to think how much can change in the course of a few years, but at least these remarkable artifacts remain to give us, amongst much else, an idea of the gardens created by the kings of Assyria.

Sunday, September 23, 2018

A view of the gardens of the Palais du Luxembourg

'After walking through a play area, as usual not very pretty – poorly designed swings and toboggans, painted in glaring colours, since it is an established fact that children have no taste – I enter a piece of woodland that seems almost wild, as the gardeners have taken care to let it grow with the least constraint possible. Then, between the edge of this forest and the side of the square, marked by the walls of the Mobilier National, in the centre of the open space we find a 'creation' – in the sense that Encelade's copse at Versailles is a creation. There is a topiary quincunx of box bushes, with roses in the middle: four open semi-cylindrical arbours frame a small obelisk of raw stone. The roses climb over the arbours and embrace the obelisk. To give an idea of the charm of the place, you have to recall one of those painters who were not landscape artists but painted almost by chance a single landscape – I have in mind the Villa Medici Gardens by Velázquez, or David‘s view of the Luxembourg, painted from the cell where he awaited the guillotine after Thermidor.'

- Eric Hazan, describing the Square René-Le Gall in A Walk Through Paris, translated by David Fernbach, 2018

Reading this passage I thought it was an interesting way of describing the charm of an urban park, encountered as unexpectedly as these modest landscape views among the works of artists known for their figure painting. I wrote here last year about the Velázquez, but what of David's painting? There was actually a good article devoted to it in The Independent a few years ago, by Michael Glover. In the course of it h, discusses details like that group of figures engaged in some sort of activity.

'Are these people raking the earth itself? Are they mark-making? Are they engaged in an inscrutable game of some kind? What we do know for certain is that after the Revolution, parts of the Luxembourg Gardens were handed over to be tilled by the common people – in the new spirit of egalitarianism, no doubt. There is not much to be tilled here though, not at this time of year, not much evidence at all of Keats's season of mellow fruitfulness.'Why was David confined to this cell? I have written a post here before about the artificial landscape he designed for the first Celebration of the Supreme Being in June 1794. This marked the zenith of Robespierre's power - already people were turning against him and within a month he had been guillotined. David, apparently ill, managed to avoid the same fate but was eventually arrested and spent August to December 1794 in prison. Michael Glover reads the politics of revolution into the landscape David painted there.

'Two factors seem to be at odds with each other in this painting: order and disorder. That fence looks makeshift in the extreme – shockingly makeshift for such an august location. And yet the layout of the gardens themselves, that perfect alignment of trees, for example, somewhat reminds us of how the Luxembourg Gardens are these days, a project that depends for its grandeur and its power to impress upon the taming and ordering of nature in the interests of human reason. And so it is here. But the tops of the trees tell quite a rather story. In these gardens, we are used to the sight of severely pollarded trees. Nature is to be tamed and regulated. Here things have got out of hand. The unruly crowns of the trees are rejoicing in their untamed spirit.'He concludes by imagining David, in his high prison cell looking down on this view. 'Meditating upon partially untamed nature in this way may have helped his spirit to breathe.'

Friday, May 11, 2018

Shanglin Park

One of the most famous descriptions of landscape in Chinese literature must be the Shanglin fu, 上林賦,, composed by Sima Xiangru. It was written for the young Emperor Wu, who had summoned Sima to court in 137 BCE, and it describes the royal hunting park southwest of the capital Chang'an. There is a magnificent Ming Dynasty scroll attributed to Qiu Ying (c. 1494-1552) which illustrates the poem - I have extracted a few details to illustrate this blog post. The first one above shows the poem's three narrators in discussion. Burton Watson translates their names as Sir Fantasy, Master No-Such and Lord Not-Real. In the first part of the fu, Sir Fantasy and Master No-Such describe hunts in Chu and Qi; in the second part, Lord Not-Real blows them away with his description of the far-more-extensive parkland of Shanglin and the hunting and entertainment that goes on there. The park is shown to be not just representative of China, but a microcosm of the whole universe.

The fu rhyme-prose form became known for its ornate language and lists (in an earlier post I referred to a 5th century critic of Sima's poetry, who complained that his 'characters were strung together like fish'). This could make it difficult to translate, but Burton Watson does it brilliantly, as Lucas Klein explains in his preface to the recent reprint of Watson's Chinese Rhyme Prose (1971, 2015). Watson, a contemporary of the Beat poets, 'reaches beyond Snyder and Ginsberg, past Rexroth and Pound, back to Walt Whitman.' Klein quotes this example from near the beginning, where Sir Fantasy is describing the hunting park he had seen in Chu (Watson explains that some of the plant names he uses are necessarily guesswork):

Here too are precious stones: carnelians and garnets,

Amethysts, turquoises, and matrices of ore,

Chalcedony, beryl, and basalt whetstones,

Onyx and figured agate.

To the east stretch fields of gentians and fragrant orchids,

Iris, turmeric, and crow-fans,

Spikenard and sweet flag,

Selinea and angelica,

Sugar cane and ginger.

As my theme here is landscape, here is a brief summary of the first part of the Shanglin Park section of the poem:

- Eight rivers are described, 'twisting and turning their way / through the reaches of the park' until eventually they reach giant lakes, 'shimmering and shining in the sun.'

- Then the poem moves in, to list the dragons and turtles that inhabit these lakes and rivers, the precious stones on their beds and the waterfowl that 'flock and settle upon the waters, drifting lightly over the surface.'

- Next the mountains and valleys are recalled, with the hills and islands at their base and the level land beyond.

- There follows a long list of the flowers and herbs that line the river banks and spread over the plains, wafting a hundred perfumes upon the air.

- After conveying a sense of the park's vast scale, the poem lists some of its exotic animals: zebras, aurochs, elephants, rhinoceroses.

- It then mentions the emperor's palaces, retreats and mountain halls, with their fabulous grottoes and gardens. There are fruit trees and flowers, dense copses and forests that blanket the mountain slopes.

- Finally, before getting on to the hunt itself and the activities of the courtiers, the poem describes apes, gibbons and lemurs, sporting among the trees and chasing over bridgeless streams.

There is obviously some exaggeration going on in this poem, so what was Shanglin Park really like? In Mark Edward Lewis's book The Early Chinese Empires, he writes that Emperor Wu installed in it 'rare plants, animals, and rocks that he had received as tribute from distant peoples, as booty from expeditions to Central Asia, or as confiscations from private collectors. The emperor's exotica included a black rhinoceros, a white elephant, talking birds, and tropical forests.' The park contained a palace complex and an artificial lake with a statue of a whale which has recently been found during an archaeological excavation. Emperor Wu's ambitious landscape gardening would be emulated by later Chinese rulers - see for example my post here on the Song Dynasty Emperor Huizong's rock garden. And Emperor Wu lived only a century or so after the First Emperor, whose mausoleum with its rivers of mercury and terracotta army was a kind of dead equivalent to the abundant parkland described by Sima Xiangru.

Friday, July 14, 2017

View of the Garden of the Villa Medici

In the course of her fascinating book on Velázquez, The Vanishing Man, published last year, Laura Cumming writes about 'a picture without precedent.' The View of the Garden of the Villa Medici 'seems to have no pretext, no definitive narrative or focus. A fragmentary glimpse, strikingly modern in its random observations, it is simply itself - the momentary scene.' Velázquez was in Rome in 1630 and knew Poussin and Claude, who were painting their great classical landscapes at this time. But 'to depict nature purely for itself, live and unadorned - in its natural state, as it were - was very much the innovation of Velázquez.' Cumming sees nothing similar in art before Corot, 'whose silvery landscapes with their secretive air have a genetic link back to Velázquez'. But is it really the case that Velázquez was so ahead of his time?

In Western art, earlier 'independent' landscape paintings, going back to Albrecht Altdorfer, do not have the air of real places seen at real moments. There are plein air sketches that have this quality, but they do not resemble the Velázquez either. Claude made such studies in the Roman Campagna and the example below is by another contemporary, Van Dyck, who was court painter to Charles I while Velázquez worked for Philip IV of Spain (The Vanishing Man is about a portrait of the young Charles that was apparently painted by Velázquez, or possibly by Van Dyck, or maybe neither...) The View of the Garden of the Villa Medici is different, more reminiscent of certain oil sketches made in the late eighteenth century (the cloth on the balcony is like the washing hung out on Thomas Jones' A Wall in Naples). It could have been a sketch of this kind, but the Prado's curators (quoting Javier Portús) say that it is currently considered to be a finished, self-sufficient work.

Laura Cumming describes The Vanishing Man as 'a book of praise for Velázquez, greatest of painters.' She writes effusively about the brilliant and subtle ways he found to apply paint to canvas. In the View of the Garden of the Villa Medici, which is relatively small (48.5 x 43 cm), she notices something remarkable.

'The weave of the cloth is exactly the right size to imitate the pattern of bricks at that distance. This is one of Velázquez's unimaginably subtle calculations. How could he guess in advance, or did it come to him as he painted? This is a great question with his art: what grows out of what, how it all evolves at leisure, or at speed, by chance or design. But what one sees here is something akin to precision engineering, in terms of vision and judgement: each brick finds its tiny outline in the grid of threads.'

Perhaps surprisingly, Cumming makes no mention of the fact that this painting of the Villa Medici has a companion piece, also in the Prado: a view of the same structure seen from a different angle, but with more prominent foreground figures. It is a marvellously strange, enigmatic image; in the background a man looks out at the distant view, like a Romantic Rückenfigur, and beside him the statue of sleeping Ariadne foreshadows the sequence of mysterious Ariadne paintings de Chirico painted in 1912-13. There might originally have been two more of these paintings. It may be that what we have now 'are two of the four little landscapes that the artist sold to Phillip IV in 1634' (Portús). The disappearance and reappearance of artworks is central to The Vanishing Man and now, after having read it, I can't help wondering about the possibility of other Velázquez landscapes one day coming to light.

Friday, June 30, 2017

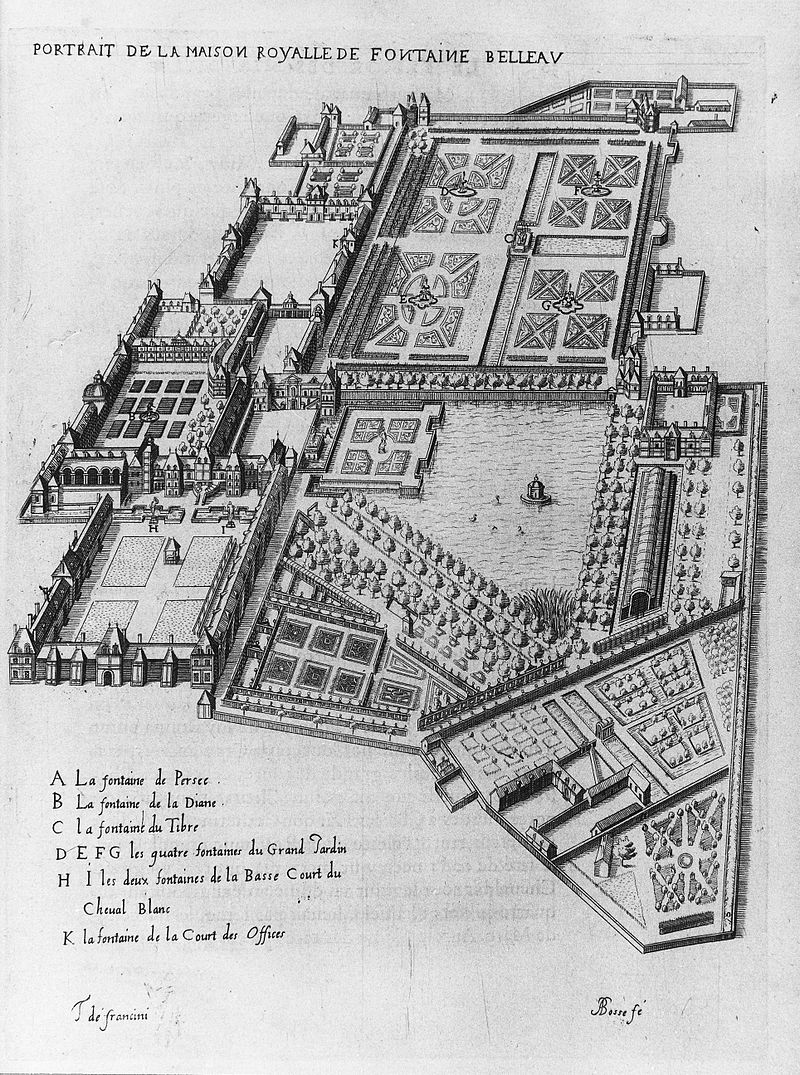

The Gardens of Fontainebleau

The Forest of Fontainebleau has a special place in the history of western landscape art: painted repeatedly by the Barbizon School and the Impressionists who took inspiration from them. That there is still a forest to explore is down in part to Théodore Rousseau: he 'appealed to Napoleon III to halt the wholesale destruction of the forest’s trees, and in 1853 the emperor established a preserve to protect the artists’ cherished giant oaks' (see the Met's online essay on the Barbizon School). We were in Fontainebleau on that fiercely hot weekend earlier this month and I yearned to head into the forest to find some of that deep shade painted by Rousseau's friend Narcisse Virgilio Díaz. But we'd come for culture rather than nature, to visit the Château de Fontainebleau. Emerging from its opulent rooms in the full heat of the afternoon we made our way across the Grand Parterre, with its low hedges and topiary cones stretching into the distance. This flat, mathematical space, planned out by André Le Nôtre and Louis Le Vau, is as different a landscape as can be imagined from the dense wooded slopes and tenebrous clearings explored by the Barbizon painters. Strange then to find at its centre, beneath the surface of a square ornamental pool, a miniature forest, swaying gently in the cool, clear water.

Before the Barbizon School there was the School of Fontainebleau, two schools in fact, the first comprising artists brought to decorate the palace during the sixteenth century (including Benvenuto Cellini, who describes the work in his wonderfully vivid Autobiography), the second at the beginning of the seventeenth during one of the phases of renovation and redecoration that continued down to Napoleon's time. These Mannerist artists were much more interested in mythological figures and allegorical references than in anything to do with landscape, as can be seen in the print below, where a rocky scene is completely dominated by its framing figures. There are numerous references to hunting in their decorative schemes: the forest as resource for the king's pleasure. The Palace contains a Gallery of Diana and a Gallery of Stags. There is also a Jardin de Diane, with a fountain dating from the early nineteenth century dedicated to the goddess; its water comes from the mouths of stags and, as my son's were quick to point out, four "pissing dogs".

The Carp Lake visible in the seventeenth century plan shown above is still there (as are the carp). The photograph of it below was taken from a rowing boat that I was pressed into hiring. The lake at Fontainebleau can also be seen in one of the Valois Tapestries, made to commemorate eight of Catherine de' Medici's famous court festivals. This one took place in 1564 and was just one event in the royal progress that took her and her son, the new king, two and a half years to complete. The household accompanying them included her 'flying squadron' (L'escadron volant) of eighty seductive ladies-in-waiting, and nine dwarfs who travelled in their own miniature coaches. The great poet Pierre de Ronsard was present at Fontainebleau, where there were feasts, jousts, sirens singing, Neptune floating in his chariot and an attack on an enchanted island. I wonder how many of them thought about the real forest beyond the Château as they acted out imaginary battles in an artificial landscape. A century later the island in the lake was given a small pavilion; later it was restored by Napoleon. We were warned as we climbed into the boat not to row too close it, although I don't think our inept collective efforts at steering could have got us there anyway.

Thursday, June 01, 2017

The Gibberd Garden

We made a trip this week to see Sir Frederick Gibberd's garden, created between 1957 and 1984, and located just outside Harlow, the New Town for which he was chief architect. Gibberd's best known design is probably Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral (aka 'Paddy's Wigwam'), a building I've always rather liked although Gibberd himself was sued for £1.3m over leaks and defects in the tiling (which have had to be replaced). He was also involved in some key post-War industrial buildings - the original Heathrow Terminal buildings, the recently-demolished Didcot A Power Station - and a few of his garden's metal and concrete sculptures and salvaged objects have the look of once-futuristic constructions that have seen better days. As a private collector Gibberd wouldn't have had resources to buy sculptures by world-renowned artists, although there is a piece by David Nash (see below). Nor can the artworks compete with those made by practising artists like Barbara Hepworth and Ian Hamilton Finlay for their own gardens. But Gibberd, as a planner and landscape architect, made good use of the site, turning the hillside and stream into a sequence of spaces with some sculptures set to catch the eye and others that you almost stumble upon.

There is an article about Gibberd by his grandson that praises the moated castle he built for his grandchildren in one corner of the site using recycled pieces of wood - my sons certainly enjoyed this too. The garden feature we liked best was also recycled - two mossy Corinthian columns shaded by trees with real acanthus growing at their base to echo the stone foliage above. This 'temple' fragment could almost have come from that erotic Renaissance idyll, the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili; in fact the pillars were designed in 1831 by John Nash for a commercial building on The Strand in London, and salvaged by Gibberd when his firm redesigned it in the 1970s for Coutts Bank. I am sure they are more appreciated in this garden among the trees than they would be on what is now the eighteenth most polluted street in Britain.

The garden must have been a pleasant place to relax in, but whether it was possible to enjoy it as a classical retreat or hortus conclusus I rather doubt. I tried to record a chaffinch singing over the bright sound of water in the brook but by the time I had my phone out all you could hear was the slow rumble of an aeroplane flying overhead. The embankment at the end of the garden carries a busy train line into Harlow. Sculptures are largely absent from the adjacent arboretum, making all the more noticeable some overhead wires crossing the space above and a line of warning signs (see above) marking the presence of a gas pipeline under the grass. You suspect though that Gibberd would not really have minded all these reminders that the garden is not separated off from the modern world he was so active in designing

.jpg/1024px-Weimar_R%C3%B6misches_Haus_an_der_Ilm%40Goethe-Nationalmuseum_(1).jpg)