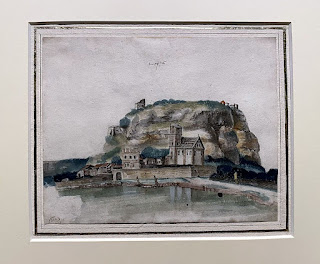

Eugène Delacroix, Sunset, c. 1850

I have been reading the Journals of Eugène Delacroix in a lovely, pristine Folio edition I found in a secondhand bookshop in York (the selections were originally translated by Lucy Norton for Phaidon in 1951). Most of what Delacroix writes about concerns art - how to achieve the effects he wants and admires in great artists of the past like Rubens and Titian. Landscape art as such was not a particular concern for him, although he was always looking at the way other artists painted skies, trees and waves. The appeal of the journals is the way they mix his ideas on aesthetics with everyday concerns - health, relationships, conversations, travel. I thought here I would just extract a few moments where he writes about walks in nature and describes views with the eye of a great painter. In 1849 he was fifty-one and dividing his time between Paris and Champrosay, now in the city's southern suburbs, with holidays on the Normandy coast near Dieppe.

Champrosay, 24 June 1849

In the morning it had been thundery and oppressive, but by the afternoon the quality of the heat had changed and the setting sun lent everything a gaiety which I never used to see in the evening light. I find that, as I grow older, I am becoming less susceptible to those feelings of deepest melancholy that used to come over me when I looked at nature, and I congratulated myself on this as I walked along.

Valmont, 9 October 1849

We went down to the sea by a little path on the right which was unfamiliar to me. There was the loveliest greensward imaginable, sloping gently downwards, from the top of which we had a view of the vast expanse of sea. I am always deeply stirred by the great line of the sea, all blue or green or rose-coloured - that indefinable colour of a vast ocean. The intermittent sound reaches from far away and this, with the smell of the ozone, is actually intoxicating.

Cany, 10 October 1849

Magnificent view as we climbed the hill out of Cany; tones of cobalt in the green masses of the background in contrast to the vivid green and occasional gold tones in the foreground.

Champosay, 27 October 1853

Went for a stroll in the garden and then stood for a long time under the poplars at Baÿvet; they delight me beyond words, especially the white poplars when they are beginning to turn yellow. I lay down on the ground to see them silhouetted against the blue sky with their leaves blowing off in the wind and falling off about me.

Paris, 5 August 1854

A lump of coal or a piece of flint may show in reduced proportions the form of enormous rocks. I noticed the same thing when I was in Dieppe. Among the rocks that are covered by the sea at high tide I could see bays and inlets, beetling crags overhanging deep gorges, winding valleys, in fact all the natural features which we find in the world around us. It is the same with waves which are themselves divided into smaller waves and then subdivided into ripples, each showing the same accidents of light and the same design.

Dieppe, 25 August 1854

During my walk this morning I spent a long time studying the sea. The sun was behind me and thus the face of the waves as they lifted towards me was yellow; the side turned towards the horizon reflected the colour of the sky. Cloud shadows passing over all this made delightful effects; in the distance where the sea was blue and green, the shadows appeared purple, and a golden and purple tone extended over the nearer part as well, where the shadow covered it. The waves were like agate.

Dieppe, 17 September 1854

A rather miserable dinner. However, when I went down to the beach, I was compensated by seeing the setting sun amidst banks of ominous-looking red and gold clouds. These were reflected in the sea, which was dark wherever it did not catch the reflection. I stood motionless for more than half an hour on the very edge of the waves, never growing tired of their fury, of the foam and the backwash and the crash of the rolling pebbles.