In this picture Kasimir Stummel, a young man employed in the Rakkóxian Department of Invention, is suggesting a grand project to Rakkóx, the eccentric

multi-billionaire who is obsessed with spending his money on ever more grandiose schemes. "When one wants to build on a grand scale," Stummel says, "it is prudent to make use of existing natural features, so that in the end it appears that one has created nature as well." But what he asks is something far more ambitious - "you could transform not merely pieces of rock, but rather an entire cliff from top to bottom into a work of architectural art? That truly would be a great thing, and would encourage coming generations over the course of the next millennium to convert the entirety of the Earth's surface into a great work of architectural art."

Later in the story the two men stand looking out over the moonlit ocean and Stummel provides further details of this concept. In recent years artists like Michael Heizer may have carved huge structures out of the landscape but what Stummel describes is a means of sculpting the landscape into new forms of habitation.

'There are a number of mountains that can easily be brought into a rectangular architectural form, and gleaming, complexly curved architectural compositions can be created, as well. The halls that will be created within the Rakkóx cliffs will be of unprecedented dimensions, modern dimensions. The new machines work so reliably that cave-ins need not be feared. Furthermore, our mathematicians work almost too carefully. I will cut off the entire top of the Cliffs of Kasimir so there can be a skylight in every hall. I imagine the halls being almost completely filled with apartments - back porches, porticoes, and balconies of any expanse desired may be included. The granite halls will appear immense. Two hundred metres high - smooth as glass! And the lighting will be torchlight. In the lower levels there will be huge rooms for taking the waters - with fountains, cascades, ponds and gondolas. Compared to these palace mountains the great cathedrals are not worthy of attention, wouldn't you agree?'

Paul Scheerbart photographed by Wilhelm Fechner, 1897

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Paul Scheerbart's visionary science fiction and writings on architecture have been attracting increasing attention. New translations into English have begun to appear - see for example the

review of

Lesabéndio: An Asteroid Novel at Hyperallergic (Alfred Kubin's original illustrations can be seen at

50 Watts). If you are not familiar with Scheerbart, I recommend profiles of his work at

Writers No One Reads or the

NYRB Blog. The University of Chicago Press have now published an introductory anthology,

Glass! Love!! Perpetual Motion!!!: A Paul Scheerbart Reader (see 'Dreams from a Glass House', a

Paris Review interview with Josiah McElheny, who co-edited it). Writing about this book for

Apollo, Owen Hatherley, notes that Scheerbart's manifesto on '

Glass Architecture was rediscovered in the English-speaking world by Reyner Banham in his 1960 book,

Theory and Design in the First Machine Age,

which presents Scheerbart, with Marinetti and Malevich, as one of

the inadvertent fathers of the modern movement in architecture and

design.' An

Architect piece on

Glass! Love!! Perpetual Motion!!! describes Scheerbart as a precursor of Archigram, the Japanese Metabolists and Rem Koolhaas.

Kina Balu from Pinokok Valley, lithograph, 1862

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Scheerbart's fictional version of the contemporary starchitect is Edgar Krug, the hero of his last novel

The Gray Cloth, published in 1914, the same year as his manifesto on

Glass Architecture. As Krug flies round the world in his airship, responding to new commissions for glass architecture, some of his designs approach the ambition of Rakkóxian cliffs. At one point he describes having to dissuade a client from converting Mount Kinabalu in Borneo into a pyramid, arguing that its mountain form should be retained but that it could be 'made habitable' with restaurants, terraces and baths. Coming to see how work has progressed, Herr Krug arrives at night, seeing the mountain summit illuminated by the spotlights of airships and aeroplanes already there. He and his companions admire the lever-trains which transport people rapidly up the mountain, using five-hundred-meter-long lever-arms. They enjoy a lantern festival and visit a large glass hall with shells embedded in its walls. On the night before they leave, they look out on the ocean from the mountain-top restaurant. 'The moon was not to be seen. Meteors moved along parabolic lines across the starry skies. On the horizon Venus was radiant.'

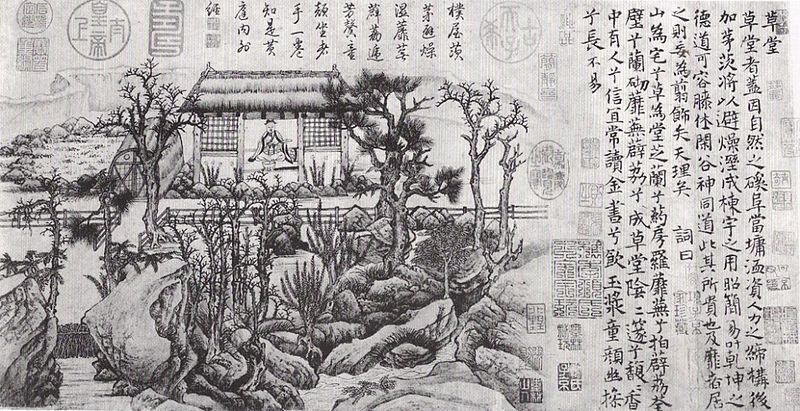

Bruno Taut, Glass House, 1914

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Scheerbart considered his collaboration with Bruno Taut on the Glass House at the Cologne Werkbund Exhibition to be 'the greatest event in my life.' After Scheerbart's death in 1915, Taut formed a circle of German expressionist architects, The Crystal Chain, and wrote his own book in which a mountain landscape is transformed,

Alpine Architecture (1919). Composed in the last years of the war, it opposed utilitarian and materialistic culture with an ideal city of glass, built on the mountain tops and reflected in their lakes. These ideas were a manifestation of the vision Scheerbart had set out in his manifesto on

Glass Architecture:

'If we want our culture to rise to a higher level, we are obliged, for

better or for worse, to change our architecture. And this only becomes

possible if we take away the closed character from the rooms in which we

live. We can only do that by introducing glass architecture, which lets

in the light of the sun, the moon, and the stars, not merely through a

few windows, but through every possible wall, which will be made

entirely of glass—of coloured glass.'

Bruno Taut, Alpine Architecture, seen from the Monte Generoso, 1919

.jpg/1280px-Het_Strand_van_Scheveningen%2C_Adriaen_van_de_Velde_(1658).jpg)

.djvu/page11-439px-Fingal_(Ossian%2C_1762).djvu.jpg)

.jpg/297px-Muso_Soseki_(Jissa-in).jpg)