I remembered how from the air the valleys, hills and rivers gained a certain distinction but wholly lost that quality which is perceived by a countryman whose day's travel is bounded by the earth of three of four meadows, and whose view for most of his life may be constricted by some local rising of the ground. In the air there is no feeling or smell of earth, and I have often observed that the backyards of houses or the smoke curling up through cottage chimneys, although at times they seem to have a certain pathos, do as a rule, when one is several thousand feet above them, appear both defenceless and ridiculous, as though infinite trouble had been taken to secure a result that has little or no significance.

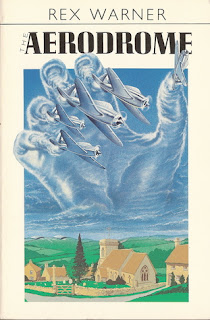

This is a paragraph from Rex Warner's novel about the arrival of an aerodrome in the middle of the English countryside. It was published in 1941 and I am sure there must be many other stories from this period with Nietzschean pilots who look down on historic landscapes that can no longer contain them. In John Cowper Powys's A Glastonbury Romance (1932) the industrialist Philip Crow purchases his own aircraft to fly to Wookey Hole, the extraordinary cave system that he wants to fill with modern electric lights and then transform with a tin mining operation.

As he watched down upon the earth, that clear March evening, and watched the chess-board fields pass in procession beneath him, and watched the trees fall into strange patterns and watched the villages, some red, some brown, some grey, according as brick or stone or slate predominated, approach or recede, as the plane sank or rose, Philip's spirit felt as if it had wings of its own ... How small and unimportant Wells cathedral had looked from up there. ... His brain whirled with the vision of an earth-life dominated absolutely by Science, of a human race that had shaken off its fearful childhood and looked at things with a clear, unfilmed, unperverted eye.

But at the end of the novel a flood inundates Glastonbury. Mayor Geard, who has tried to create a new spiritual centre drawing on the town's legendary past, feels his earthly work is done and heads off in a small boat. He comes upon his antagonist Philip Crow, who is keeping his head above water by standing on his submerged plane. Geard surprises Crow by asking to swap places. Crow needs little persuading and Geard leaves the boat to rest on the plane as it gradually sinks. At one point he kicks it to help it on its way. Eventually the wing beneath him disappears and Geard, with one final glimpse of Glastonbury Tor, follows it down.