James Norrie and Jan Griffier II, Panorama of Taymouth Castle and Loch Tay, c. 1733-9

I recently wrote here about Daniel Defoe's A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain, focusing on his remarks about Derbyshire. I mentioned the wealth of illustrations in the Yale Press edition and some of the colour reproductions are spectacular, a full page for example given over to one detail in the painting above, showing soft light on the distant Loch Tay. It's a shame there aren't more because some of the book's small black and white images are equally remarkable, like Balthasar Nebot's painting of extreme topiary that looks like it has come from the imagination of Giorgio De Chirico. As these two examples indicate, many of the artists represented in the book came from abroad, particularly the Low Countries: Johannes Kip, Herman Moll, Jan Siberechts, Peter Tillemans. Other groupings of topographical artists might be made: antiquarians, professional painters and engravers, or artists associated with the military: Paul Sandby, Greenville Collins, John Slezer. Slezer came over to Scotland from Holland in 1669 but was a supporter of James VII rather than William of Orange and went to prison for it. Defoe, a great supporter of King William, was writing just after the Act of Union and subsequent uprising by James's son, the Old Pretender. His observations on Scotland have a particular resonance today.

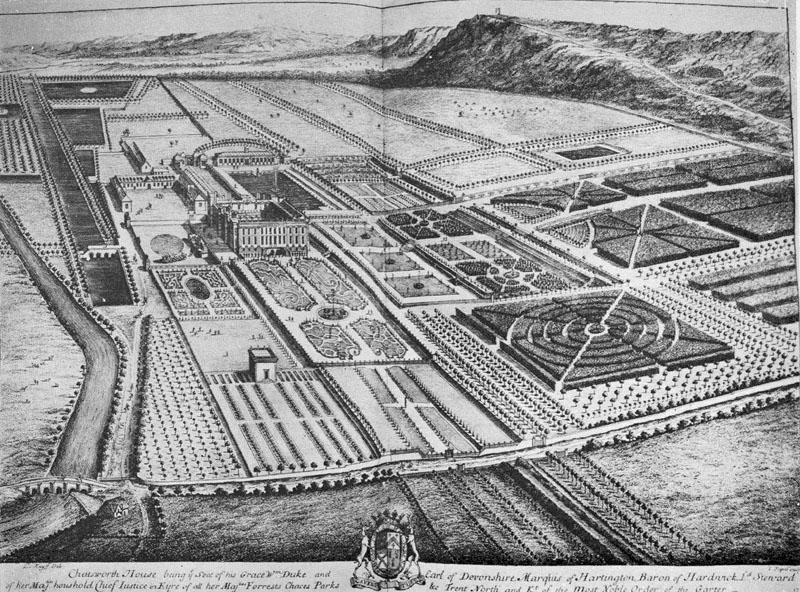

Balthasar Nebot, Garden View of Hatwell House, 1738

Defoe is not generally very expansive on matters of landscape, but here are ten miscellaneous quotes that I thought worth noting. The final illustration below also appears in the Yale edition and shows the kinds of trading and commercial activities Defoe was really most interested in recording.

- Essex: the effect of the marshes on the people - 'all along this county it was very frequent to meet with men that had had from five or six, to fourteen or fifteen wives; nay, and some more ... The reason, as a merry fellow told me, who said he had had about a dozen and half of wives, (tho' I found afterwards he fibb'd a little) was this; That they being bred in the marshes themselves, and season'd to the place, did pretty well with it; but that they always went up into the hilly country, or to speak their own language into the uplands for a wife: That when they took the young lasses out of the wholesome and fresh air, they were healthy, fresh and clear, and well; but when they came out of their native air into the marshes among the fogs and damps, there they presently chang'd their complexion, got an ague or two, and seldom held it above half a year, or a year at most; and then, said he, we go to the uplands again, and fetch another...'

- Harwich: a town paved with petrified clay - 'there is a sort of clay in the cliff, between the town and the beacon-hill adjoining, which when it falls down into the sea, where it is beaten with the waves and the weather, turns gradually into stone: but the chief reason assign'd, is from the water of a certain spring or well, which rising in the said cliff, runs down into the sea among those pieces of clay, and petrifies them as it runs ... The same spring is said to turn wood into iron: But ... I presume, that those who call the harden' d pieces of wood, which they take out of this well by the name of iron, never try'd the quality of it with the fire or hammer; if they had, perhaps they would have given some other account of it.'

- Bagshot-Heath: a desert in Surrey - 'Those that despise Scotland, and the north part of England, for being full of wast and barren land, may take a view of this part of Surrey, and look upon it as a foil to the beauty of the rest of England ... here is a vast tract of land, some of it within seventeen or eighteen miles of the capital city; which is not only poor, but even quite steril, given up to barrenness, horrid and frightful to look on, not only good for little, but good for nothing; much of it is a sandy desert, and one may frequently be put in mind here of Arabia Deserta, where the winds raise the sands, so as to overwhelm whole caravans of travellers, cattle and people together; for in passing this heath, in a windy day, I was so far in danger of smothering with the clouds of sand, which were raised by the storm, that I cou'd neither keep it out of my mouth, nose or eyes; and when the wind was over, the sand appeared spread over the adjacent fields of the forest some miles distant, so as that it ruins the very soil.'

- Surrey: the effect of chalk on a traveller - 'From this town of Guilford, the road to Farnham is very remarkable, for it runs along west from Guilford, upon the ridge of a high chalky hill, so narrow that the breadth of the road takes up the breadth of the hill, and the declivity begins on either hand, at the very hedge that bounds the highway, and is very steep, as well as very high; from this hill is a prospect either way, so far that 'tis surprising; and one sees to the north, or N.W. over the great black desart, call'd Bagshot-Heath, mentioned above, one way, and the other way south east into Sussex, almost to the South Downs, and west to an unbounded length, the horizon only restraining the eyes: This hill being all chalk, a traveller feels the effect of it in a hot summer's day, being scorch'd by the reflection of the sun from the chalk, so as to make the heat almost insupportable; and this I speak by my own experience.'

- London: swallowing up the surrounding villages - 'It is the disaster of London, as to the beauty of its figure, that it is thus stretched out in buildings, just at the pleasure of every builder, or undertaker of buildings, and as the convenience of the people directs, whether for trade, or otherwise; and this has spread the face of it in a most straggling, confus'd manner, out of all shape, uncompact, and unequal ... We see several villages, formerly standing, as it were, in the country, and at a great distance, now joyn'd to the streets by continued buildings, and more making haste to meet in the like manner ... That Westminster is in a fair way to shake hands with Chelsea, as St. Gyles's is with Marybone; and Great Russel Street by Montague House, with Tottenham-Court: all this is very evident, and yet all these put together, are still to be called London: Whither will this monstrous city then extend? and where must a circumvallation or communication line of it be placed?'

- The Fens: the ominous sound of bitterns - 'This part is indeed very properly call'd Holland, for 'tis a flat, level, and often drowned country, like Holland itself; here the very ditches are navigable, and the people pass from town to town in boats, as in Holland: Here we had the uncouth musick of the bittern, a bird formerly counted ominous and presaging, and who, as fame tells us, (but as I believe no body knows) thrusts its bill into a reed, and then gives the dull, heavy groan or sound, like a sigh, which it does so loud, that with a deep base, like the sound of a gun at a great distance, 'tis heard two or three miles, (say the people) but perhaps not quite so far.'

- Nottingham: its vaults and cellars - 'The town of Nottingham is situated upon the steep ascent of a sandy rock; which is consequently remarkable, for that it is so soft that they easily work into it for making vaults and cellars, and yet so firm as to support the roofs of those cellars two or three under one another; the stairs into which, are all cut out of the solid, tho' crumbling rock; and we must not fail to have it be remember'd that the bountiful inhabitants generally keep these cellars well stock'd with excellent ALE; nor are they uncommunicative in bestowing it among their friends. as some in our company experienc'd to a degree not fit to be made matter of history.'

- Yorkshire: magical springs - 'The country people told us a long story here of gipsies which visit them often in a surprising manner. We were strangely amused with their discourses at first, forming our ideas from the word, which, in ordinary import with us, signifies a sort of strolling, fortune-telling, hen-roost-robbing, pocket-picking vagabonds, called by that name. But we were soon made to understand the people, as they understood themselves here, namely, that at some certain seasons, for none knows when it will happen, several streams of water gush out of the earth with great violence, spouting up a huge heighth, being really natural jette d'eaus or fountains; that they make a great noise, and, joining together, form little rivers, and so hasten to the sea. I had not time to examine into the particulars; and as the irruption was not just then to be seen, we could say little to it: That which was most observable to us, was, that the country people have a notion that whenever those gipsies, or, as some call 'em, vipseys, break out, there will certainly ensue either famine or plague.'

- Dumfries: a fine palace in a hideous landscape - 'We could not pass Dumfries without going out of the way upwards of a day, to see the castle of Drumlanrig, the fine palace of the Duke of Queensberry ... Drumlanrig, like Chatsworth in Darbyshire, is like a fine picture in a dirty grotto, or like an equestrian statue set up in a barn; 'tis environ'd with mountains, and that of the wildest and most hideous aspect in all the south of Scotland; as particularly that of Enterkin, the frightfullest pass, and most dangerous that I met with, between that and Penmenmuir in North Wales; but of that in its place...'

- Stirling: the meanders of the River Forth - 'The Governor's lady (who was the Countess Dowager of Marr, when we were there, and mother of the late exil'd Earl of Marr), had a very pretty little flower-garden, upon the body of one of the bastions, or towers of the castle, the ambrusiers, serving for a dwarf-wall round the most part of it; and they walk'd to it from her Ladyship's apartment upon a level, along the castle-wall. As this little, but very pleasant spot, was on the north side of the castle, we had from thence a most agreeable prospect indeed over the valley and the river; as it is truly beautiful, so it is what the people of Sterling justly boast of, and, indeed seldom forget it, I mean the meanders, or reaches of the River Forth. They are so spacious, and return so near themselves, with so regular and exactly a sweep, that, I think, the like is not to be seen in Britain, if it is in Europe, especially where the river is so large also. The River Sein, indeed, between Paris and Roan, fetches a sweep something like these some miles longer, but then it is but one; whereas here are three double reaches, which make six returns together, and each of them three long Scots miles, or more in length; and as the bows are almost equal for breadth, as the reaches are for length, it makes the figure compleat. It is an admirable sight indeed.'

Unknown painter, Broad Quay Bristol, early 18th century