In an earlier

post here I mentioned the chapter Edward Thomas devoted to John Aubrey in

The Literary Pilgrim in England and his praise for the way Aubrey's description of places isolate telling details. 'Who but Aubrey would have noticed and entered

in a book the spring after the fire of London "all the ruins were

overgrown with an herb or two, but especially with a yellow flower,

Ericolevis Neapolitana."'

This attention to the more curious or illuminating facets of what he was writing about have made his biographical notes published posthumously as

Brief Lives far more popular than many worthy but dull works by his contemporaries. It occurred to me, browsing through a volume of these just now, that I might highlight here three of his subjects who had some connection with three of the arts of landscape: drawing, poetry and garden design.

Wenceslaus Hollar, St. Martin's Cathedral in Mainz, 1632

Wenceslaus Hollar (1607-77) was a Bohemian engraver, known now for his panoramic views of London. 'He told me,' writes Aubrey, 'that when he was a schoolboy he took a delight in drawing of maps; which drafts he kept, and they were pretty. He was designed by his father to have been a lawyer, and was put to that profession, when his father's troubles, together with the wars, forced him to leave his country. So that what he did for his delight and recreation only when a boy, proved to be his livelihood when a man.' Hollar's talents were spotted by the Earl of Arundel, who engaged him as a draughtsman. He travelled to Vienna with the Earl, 'very well clad', to 'take views, landscapes, buildings, etc remarkable in their journey, which we see now at the print shops.' In 1637 he came with the Earl to England and 'at Arundel House, he married my lady's waiting woman, Mrs Tracy, by whom he has a daughter, that was one of the greatest beauties I have ever seen; his son by her died in the plague, an ingenious youth, who drew delicately.'

Hollar, we are told, was very shortsighted and his landscapes were done in such detail that they are 'not to be judged without a magnifying glass.' During the Civil War he lived in Antwerp but returned in 1652. 'I remember he told me that when he first came into England (which was a serene time of peace) that the people, both poor and rich, did look cheerfully, but at his return, he found the countenances of the people all changed, melancholy, spiteful, as if bewitched.' Hollar himself 'was a very friendly good natured man as could be, but shiftless as to the world [careless in his affairs] and died not rich.'

Wenceslaus Hollar, Landscape Face, unknown date

Sir John Denham (1615-69) is of interest here as the author of '

Cooper's Hill' (1642), the first English topographical poem. Aubrey writes that at Oxford University, the young Denham 'would game extremely; when he had played away all his money, he would play away his father's wrought rich gold cups. ... From Trinity College he went to Lincoln's Inn, where (as Judge Wadham Windham, who was his contemporary, told me) he was as good a student as any in the house.' Nevertheless, on one occasion 'having been merry at a tavern with his comrades, late at night, a frolic came into his head, to get a plasterer's brush and a pot of ink, and blot out all the signs between Temple Bar and Charing Cross' (they were caught - 'this I had from R. Estcott, esquire, who carried the inkpot').

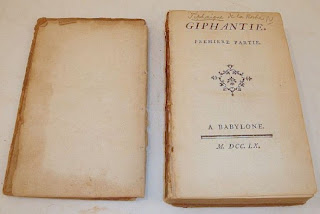

Denham's play

The Sophy was a huge success - the poet 'Mr Edmund Waller said then of him, that he '"broke out like the Irish Rebellion."' His poem 'Cooper's Hill' was published after the Battle of Edgehill 'in a sort of brown paper, for then they could get no better.' As a Royalist, Denham was not welcome during the Commonwealth but returned from abroad and eventually became Surveyor of the King's Work. 'In 1665 he married his second wife, a [Margaret] Brookes, a very beautiful young lady; Sir John was ancient and limping. The Duke of York fell deeply in love with her, though (I have been morally assured) he never had carnal knowledge of her. This occasioned Sir John Denham's distemper of madness ... but it pleased God that he was cured of this distemper, and wrote excellent verses, particularly on the death of Mr Abraham Cowley, afterwards. His second lady had no child; was poisoned by the hands of the Countess of Rochester with chocolate.'

Aubrey gives us some details of Denham's physical appearance: thin hair, a slow gait, tall but 'a little incurvetting at his shoulders, not very robust.' He 'was satirical when he had a mind to it' and 'his eye was a kind of light goose-grey, not big; but it had a strange piercingness, not as to shining and glory, but (like a Momus) when he conversed with you he looked into your very thoughts.' He describes the delight Denham took in the landscape around his home - Camomile Hill, 'from the camomile that grows their naturally', and Prunewell Hill, 'where was a fine tuft of trees, a clear spring, and a pleasant prospect to the east.' This house was near Cooper's Hill, 'incomparably well described by that sweet swan, Sir John Denham.'

Thomas Bushell (1594-1674) was a servant of Francis Bacon, from whom he learnt the science of metallurgy, and whose writings inspired him, after Bacon's death in 1626, to live for three years on the Isle of Lundy as a hermit. Having married and moved to Oxfordshire, he designed for himself an extraordinary grotto with elaborate water features, including a silver ball that rose and fell on a jet of water and a sequence of fountains designed to surprise the ladies as they walked over them. Aubrey says that it faced south 'so that when it artificially rains upon the turning of a cock [tap], you are entertained with a rainbow. In a very little pond (no bigger than a basin) opposite to the rock, and hard by, stood (1643, August 8) a Neptune, neatly cut in wood, holding his trident in his hand, and aiming with it at a duck which perpetually turned round him, and a spaniel swimming after her.' Bushell lived above this grotto in three rooms, one painted with Biblical stories concerning water, another with the story of Christ told in wall hangings and the third, a hermit's cell, hung in black baize. In 1636 Bushell presented his 'Rock' to King Charles and Henrietta Maria to the accompaniment of music - Aubrey unhelpfully notes that 'I remember the student of Christ Church which sang the songs (I now forget his name)'.

A year after the royal visit, Bushell was made King's farmer of minerals in Wales and spent the rest of his career putting Bacon's science into practise in a series of mining schemes. 'He had so delicate a way of making his projects alluring and feasible, profitable, that he drew to his baits not only rich men of no design, but also the craftiest knaves in the country ... As he had the art of running into debt, so sometimes he was attacked

and thrown into prison; but he would extricate himself again strangely.' Aubrey relates that after offending parliament or Cromwell, Bushell hid at his house in Lambeth Marsh, dating his letters as if they had been sent from overseas. He had a room there hung all in black, with a painted skeleton and 'an emaciated dead man stretched out. Here he had several mortifying and divine mottoes (he imitated his lord [Bacon] as much as he could) and out of his windows a very pleasant prospect.' He was, according to Aubrey, 'a handsome proper gentleman when I saw him at his house aforesaid at Lambeth. He was about 70, but I should not have guessed him hardly 60. He had a perfectly healthy constitution; fresh, ruddy, face; hawk-nosed, and was temperate.'

Engraving showing Thomas Bushell's hermitage at Enstone,

from Robert Plot's Natural History of Oxfordshire, 1677.

(Aubrey read this and modelled his own unfinished book about Wiltshire on it)