I was recently in Nuremberg and had been keen to see the Albrecht Dürer house, although I was a bit disappointed to be honest, hoping for something that felt a bit older and less-restored. You can see the city's castle from Dürer's upstairs windows, just the other side of a square, with walls made of distinctive red sandstone. Inside the castle they have a reproduction of the sketch above and a text explaining that this particular sandstone was laid down about 215 million years ago. 'Albrecht Dürer painted sandstone formations at rock quarries in the Nuremberg region. These rocks are still used for restoration work at the imperial castle, the Peller courtyard, or the structures at the zoo. The last quarry still in operation for Nuremberg sandstone is the one in the Lorenz Reichswald Forest.' I've uploaded a photograph from Wikimedia of this Steinbruch Worzeldorf quarry below:

Saturday, August 24, 2024

Study of a rock-face

I was recently in Nuremberg and had been keen to see the Albrecht Dürer house, although I was a bit disappointed to be honest, hoping for something that felt a bit older and less-restored. You can see the city's castle from Dürer's upstairs windows, just the other side of a square, with walls made of distinctive red sandstone. Inside the castle they have a reproduction of the sketch above and a text explaining that this particular sandstone was laid down about 215 million years ago. 'Albrecht Dürer painted sandstone formations at rock quarries in the Nuremberg region. These rocks are still used for restoration work at the imperial castle, the Peller courtyard, or the structures at the zoo. The last quarry still in operation for Nuremberg sandstone is the one in the Lorenz Reichswald Forest.' I've uploaded a photograph from Wikimedia of this Steinbruch Worzeldorf quarry below:

Monday, December 20, 2021

Dosso di Trento

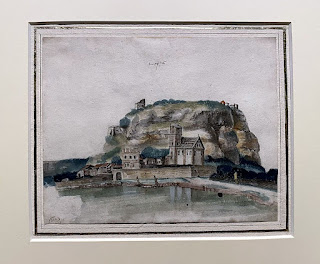

Albrecht Dürer, Trintberg - Dosso di Trento, 1495

I recently visited the National Gallery's Dürer’s Journeys: Travels of a Renaissance Artist, which I had been looking forward to all year, although I was forewarned that it would be a disappointment by Laura Cummings' Guardian review. She notes that

There is no clear chronology and barely any discernible narrative. The show feels on the one hand congested – too many passengers on board – and on the other, lacking in the forcefield presence of the German master. A humdrum portrait medal of Dürer, instead of a single one of his many self-portraits in ink, chalk, silverpoint or paint – so spectacular, so pioneering, so original – can only mean inevitable bathos. Still, there are marvels by Dürer along the way. He is up there in the Alps getting an image of the shelter down on paper: noticing the fragility of the ruined roof and the weirdly human profile of the foreground rocks...

I let that quote run on to the comment about the shelter because I too was struck by this incomplete sketch. I had been hoping to see in this exhibition some landscape sketches like the wonderful View of the Arco Valley in the Tyrol owned by The Louvre. There was just one - see my photo above: a simplified view of Trento outlined against what appears to be a blank sky. In reality Trento is surrounded by green hills and mountains. This erasure of the landscape is even more striking in his sketch of the mountain shelter from twenty years later. It's almost as if the wider view is too vast and beautiful to capture in paint and so the artist turns his back on it, ignoring the towering rocks and trees around him and electing instead to draw the crumbling stone walls and roof beams of a vulnerable human structure.

Albrecht Dürer, Ruin of an Alpine Shelter, 1515

Friday, May 22, 2020

Onuphrius in the wilderness

You could write a whole book about landscapes in depictions of the Desert Fathers and Desert Mothers (and I would read it). A chapter on Saint Onuphrius would certainly include this painting, which I photographed three years ago in Zurich. The desert here resembles a summer lawn and the little stream seems to provide just enough water to irrigate a few herbs. Also in Switzerland, the Kunstmuseum Basel has an austere landscape from 1519 in which Onuphrius prays among bare red rocks and broken tree trunks. It was painted by a local artist, Conrad Schnitt. Sadly there is no image freely available online - all I could find was one overwritten throughout with 'Alamy' to prevent copying. I'm therefore only able to provide a tiny detail below, showing a distant building that I'm guessing is the monastery Onuphrius lived in before he headed into the desert. In the Zurich painting there is a similarly-placed structure, which looks like a beautiful medieval castle standing out against the golden sky.

We only really know about Onuphrius from an account of Paphnutius the Ascetic, a fourth century Egyptian anchorite. Paphnutius ventured into the desert to see what it would be like to be a hermit and there he saw a wild man covered in hair, wearing only leaves. This was Onuphrius, who said he had survived as a hermit out there for seventy years. They spoke until sunset and spent the night in prayer. In the morning Onuphrius died and Paphnutous covered his body with a cloak and left it in a cleft in the rocks because the ground was too hard to bury him.

Cornelis Cort, Saint Onuphrius, 1574

You would think such an inhospitable place would always appear as a bleak-looking landscape in art. But this isn't always the case, as can be seen in Cornelis Cort's print. Here there are trees in full leaf and plentiful water in a wonderfully well-drawn river. I have reproduced another print below by Albrecht Dürer. It shows John the Baptist with a saint once thought to have been Saint Jerome, but as the National Gallery curators write, there is no lion to be seen and 'instead, the garland of hops points towards Saint Onuphrius.' They note that 'the relatively densely worked areas in the centre of the print contrast with almost rudimental landscape in the background.' However, for me, the distant vista is beautiful rather than 'rudimental', with its sense of space and light, and that sea fringed with trees and dotted with two small boats beneath waves of cloud...

I won't try your patience here by describing lots more images of Onuphrius in the history of art. There have been many icons in which his standing figure is placed in front of his cell, between hills or on a rocky plain. Artists whose views of the saint are set in interesting wilderness landscapes include Lorenzo Monaco (c. 1370-1425), Francesco Morone (1471-1529), Jan van Haelbeck (1595-1635), Francisco Collantes (1599-1656) and Salvator Rosa (1615-1673). I will conclude with just one more: a painting orginally made for the Buen Retiro Palace in Madrid. The artist responsible for the figure of Onuphrius is not known but the painter of the landscape is unmistakable. The life of a hermit in this sublime landscape looks almost inviting.

Saturday, April 02, 2016

The ink dark moon

I read in the New York Review recently of another new translation of Murasaki's The Tale of Genji and recalled that it is not that long ago that The Pillow Book of Sei Shōnagon was reissued in a new version by Penguin Classics. Strange then that their great contemporary Izumi Shikibu (c. 974-c. 1034) remains relatively unpublished and neglected in comparison. However, anyone curious about her poetry can find a rewarding set of translations made in the late eighties and published in 1990 by Jane Hirshfield with Mariko Aratani. Their book, The Ink Dark Moon also contains a selection of earlier poetry by Ono no Komachi (c. 834-?), the only woman writer included among the 'Six Poetic Geniuses' of Japan by Ki no Tsurayuki, writing in the Preface to the Kokinshū, c. 905.

It is a bit of a stretch to make a connection between The Ink Dark Moon's short love poems and themes of landscape, although both writers' inner emotions find their objective correlatives in the sounds, scents and colours of nature. In one of her poems Ono no Komachi, picturing the evergreen pine trees of Tokiwa Mountain, wonders whether they recognise the coming of autumn in the sound of the blowing wind. Izumi Shikibu observes that pine trees may keep their original colour, but everything that is green looks different in spring. As Jane Hirshfield says in her notes, it is interesting to see in these examples the different use made of the idea of unchanging evergreen trees. Many Japanese poems feature this trope, although it is not actually true that pine trees retain their colour, since the older needles turn brown and fall to the ground. Edwin A. Cranston mentions this in his note on a poem in the second of his monumental waka anthologies, in which a sad lover sees that 'even the treetops of the pines' are changing colour. 'The possibility of paradox is not lightly to be dismissed from poetry - or from considerations of the workings of the human heart.'

In Jane Hirshfield's own poetry written over the decades since The Ink Dark Moon she has occasionally written about Japanese and Chinese culture. 'Recalling a Sung Dynasty Landscape', for example, describes moonlit mountains and a solitary thatched hut, a place to rest the eye. She concludes that

In other poetry the influence of studying writers like Izumi comes through in the metaphors she uses. There is, for example, a poem in her collection The Beauty on 'The landscape by Dürer / of a dandelion amid grasses' (the painting appears on the cover of he Bloodaxe edition). In this she sees 'exiles / writing letters / sent over the mountains' - the exiles are the flowers and their messengers the passing horses and donkeys.... the heart, unscrolled,

is comforted by such small things:

a cup of green tea rescues us, grows deep and large, a lake.

There are two Jane Hirshfield poems in the Bloodaxe ecopoetry anthology Earth Shattering - one of which 'Global Warming' is particularly striking (you can Google it but as ever I'm trying to adhere to fair-use copyright rules here). The clip below is a short talk on ecopoetics that she delivered in 2013. It traces environmental attitudes in literature from Gilgamesh cutting down the cedar forest, to Gary Snyder, whose haibun series 'Dust in the Wind' achieves a balance between the human and natural worlds. Hirshfield wrote a beautiful poem herself in haibun form (prose:haiku) which can be found in the collection Come, Thief. It describes walks over the course of a summer in which she sees an old man building a boat until, 'finally, today, it is being painted: a clear Baltic blue.' This boat, at rest on its wooden cradle, resembles a horse waiting in a stable. She thinks of the way horses dream and of the hopes of the old man. The brief concluding poem is simply the image of that blue boat, high on a mountain among the summer trees.

Friday, July 12, 2013

Willow Mill

The latest LRB carries a piece on Dürer by Christopher S. Wood, who twenty years ago published possibly my favourite work of art history, Albrecht Altdorfer and the Origins of Landscape. This new article is a review of The Early Dürer, an exhibition catalogue edited by Daniel Hess and Thomas Eser. What he says about their self-imposed academic caution made me reflect on the freedom that blogs provide to break rules and go off on unusual tangents. 'The professional habitus of many art historians is negative, debunking, normalising,' he writes. On Dürer's sexuality,

'the catalogue simply cuts short any inquiry by invoking a normalising historical context. A drawn profile portrait of a laughing Pirckheimer, for example, signed by Dürer, is supplemented by a Greek phrase, written in Pirckheimer’s own hand: ‘with a cock up the ass’. The exhibition catalogue approvingly cites two scholars who tried to explain this inscription either as an erudite comment on the unflattering likeness or as a parody of conventional humanist epigrams. But there is surely more to be said. The catalogue comes across as pedantic if not priggish when it dismisses other scholars’ attempts to relate the inscription to Dürer’s and Pirckheimer’s sexuality as ‘methodologically problematic’'.

When it comes to landscape, the catalogue's contributors are 'unwilling to read Dürer’s works as directly registering his experience.'

'The watercolour landscapes, for example, have traditionally been seen as impressions of real places created on site during day trips or longer journeys. Rather, it is argued here, the landscapes were carefully contrived exempla or demonstration pieces, designed to establish their maker as an authority or to provide evidence of his travels: they functioned as tokens in a social game. According to the catalogue, we should not read the watercolours as engagements with the natural world because there is no evidence in written sources that artists in this period thought about landscape in such terms. One might well wonder why the authors don’t have more confidence in the drawings themselves as sources. The catalogue frequently strikes such notes of caution, as if there were a danger that the public might succumb to a thoughtless cult of genius.'Wood, on the contrary, concludes that 'Dürer’s landscape watercolours remain emblems of a new concept of artistic authorship grounded in curiosity, desire and attentiveness to the real.'

Saturday, October 16, 2010

Dream Vision in The Time of the Wolf

There has not been much time for this blog of late as I've been working on a big publication that appeared last week. It has all been rather tense, so I'm not sure why I ended up last night trying to relax by watching a typically bleak Michael Haneke film... Le Temps du Loup (The Time of the Wolf, 2003) is set after an unspecified apocalypse and begins with a family escaping from the city and then, after the father is shot, wandering through the inhospitable countryside until they meet other people waiting at an abandoned station. The hoped for train never comes, although the long take that ends the film is the view from a train. It passes through a landscape of hills, trees and valleys but with no signs of humanity anywhere.

At one point in the film Eva, the daughter, looking round the empty rooms of the station, comes across a reproduction of Dürer's Dream Vision taped to a wall (see the start of the YouTube clip below). Dürer's watercolour tried to capture his fear of an apocalypse, falling in the form of water on a landscape resembling the countryside in Le Temps du Loup. The text below it reads:

`In 1525, during the night between Wednesday and Thursday after Whitsuntide, I had this vision in my sleep, and saw how many great waters fell from heaven. The first struck the ground about four miles away from me with such a terrible force, enormous noise and splashing that it drowned the entire countryside. I was so greatly shocked at this that I awoke before the cloudburst. And the ensuing downpour was huge. Some of the waters fell some distance away and some close by. And they came from such a height that they seemed to fall at an equally slow pace. But the very first water that hit the ground so suddenly had fallen at such velocity, and was accompanied by wind and roaring so frightening, that when I awoke my whole body trembled and I could not recover for a long time. When I arose in the morning, I painted the above as I had seen it. May the Lord turn all things to the best.'

Tuesday, December 13, 2005

House by a pond

In about 1496 Albrecht Dürer painted a House by a Pond on the outskirts of Nuremburg, after returning from his first trip to

Dürer re-used this landscape in an engraving, The Madonna with the Monkey (c1498). In his book on Landscape and Western Art, Malcolm Andrews uses these two images by Dürer to discuss the issue of independent landscape painting and the distinction between landscape as setting or subject. The artist’s introduction of religious figures gives the landscape a new mood as well as a new meaning. It also illustrates the usefulness of the sketch, and the fact that it would have been difficult to conceive of a landscape like House by a Pond as a work of art in its own right.

However, the story doesn’t end there. I came across this house once again (when I was looking for images of flight) in Giulio Campagnola’s engraving The Rape of Ganymede (ca. 1500–1505). Here the Neoplatonic symbolism of the subject seems to imbue the house with a strange significance.

But this simple German landscape was not infinitely adaptable. There is a maiolica plate in the