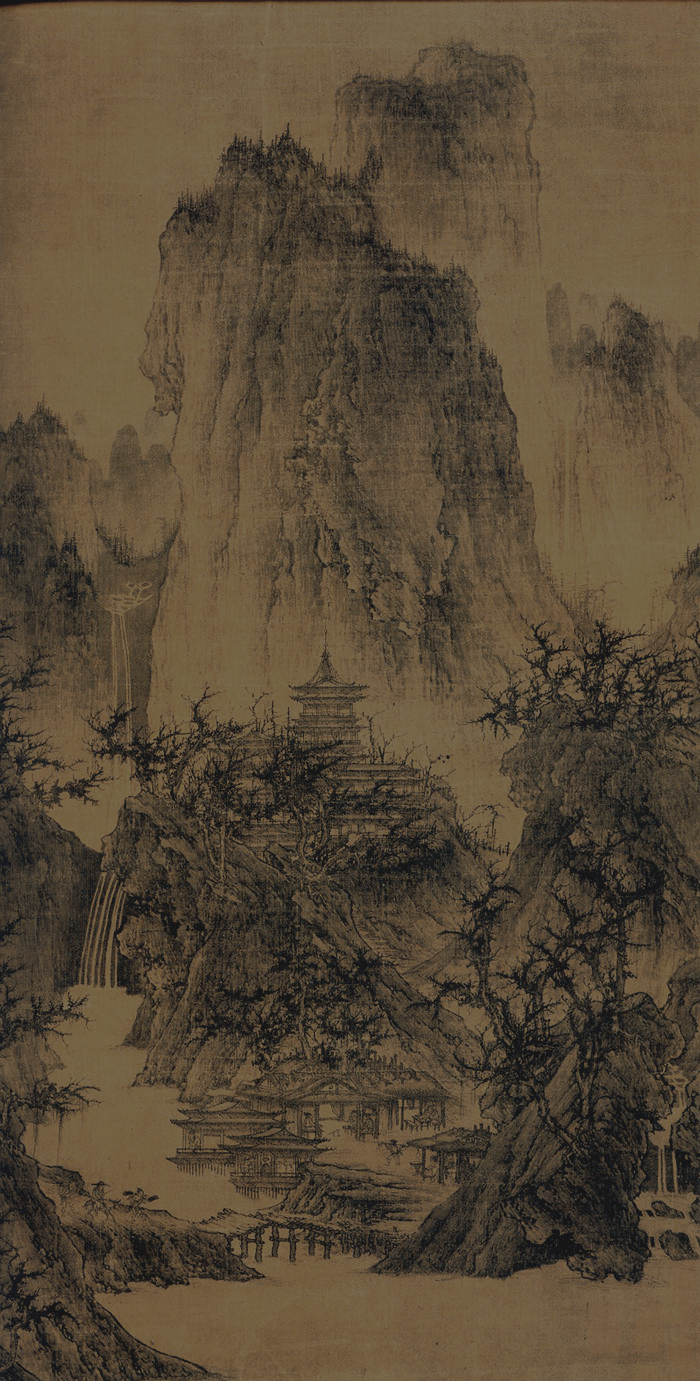

Li Cheng, A Solitary Temple Among Clearing Peaks, Song Dynasty

We have got rather behind in watching Civilisations on the iPlayer, so I have only just seen Simon Schama's episode concerning landscape, 'Picturing Paradise'. I really enjoyed it and was full of admiration for the way he explained the significance and beauty of specific works of art in a such a short space of time. The programme actually begins in twentieth century China with Mu Xin, who painted his landscapes in secret during the Cultural Revolution. His trajectory from enemy of the people to revered cultural figure culminated recently in the establishment of a Mu Xin museum in Wuzhen. Schama then takes the story back to Song Dynasty China and Li Cheng, whose paintings I wrote about last year. The way the camera pans in close over A Solitary Temple Among Clearing Peaks reveals far more detail (see below) than can be gleaned from the rather dark image of this painting (above) I've used here before.

Having devoted a decent amount of time to Li Cheng, the programme moves on to Qiao Zhongchang's handscroll illustrating The Second Prose Poem on the Red Cliff. I imagine Schama would love to have had time to give the full background on Shu Shi's poem, but he focuses on the mood conveyed in this painting, contrasting the pleasures of an excursion with the sadness of exile, "a dream, but one with a bitter-sweet taste". This Chinese section concludes with Wang Meng's Dwelling in the Qingbiang Mountains, allowing Schama to introduce themes of political symbolism - the turbulence in Song Dynasty China echoed in the way Wang painted his landscape. The idea that landscapes tell us much about the world in which they were painted is then taken up, after a brief mention of Islamic art and gardens, in his account of Western landscape art. In all, a quarter of the whole programme is devoted to Chinese landscape painting - if only this could have been expanded into a whole series...

Qiao Zhonchang, Illustration to the Second Prose Poem on the Red Cliff, Song Dynasty

By this point in the programme we had become conscious of Simon Schama's rather idiosyncratic pronunciation of certain words. 'Most of us', as Gerard O'Donovan wrote in his Telegraph review,

'put the stress on the first syllable (MOUNtain), but he places it on the second (mounTAIN). As in, say, maintain or plantain. Usually, such idiosyncrasy would go unremarked. But being devoted to landscape art, there were so many mounTAINs (and even a founTAIN) in last night’s enthralling third edition of Civilisations, you had to wonder whether he’d ever noticed it himself.'A bit harsh, but then it is hard not to focus on the mannerisms of the presenters given that they are effectively being pitched against the magisterial, patrician authority of Sir Kenneth Clark (incidentally, there's a nice clip of Clark in the original Civilisation (1969) embedded in a post I did back in 2010 about Jean-Jacques Rousseau). I was dismayed to read a few days ago an article headlined 'Mary Beard 'cut' from US version of Civilisations, fearing 'slightly creaky old lady isn't ideal for US TV'. I agree with O'Donovan that Schama's enthusiasm is inspiring to watch and that, like him, I'm happy to listen to views delivered 'with the unshakeable confidence of a man who goes through life pronouncing mounTAIN like he’d invented the word himself.'

I will not attempt to summarise the rest of the programme, which focuses on some of the themes Schama has written about before - the German forest, mercantile Holland and the American wilderness. Perhaps the fact that he has written things like Landscape and Memory explains why he has not contributed a series tie-in book, unlike the other two presenters. As for the inevitable omissions in this programme, I'm guessing Turner, Constable, Monet and Van Gogh will come in somehow to a later episode, but suspect there might be no more on post-Song Dynasty Chinese landscape art. To conclude here I will transcribe a quote from the programme which I hope conveys why I think Schama is so good. Here he takes an apparently unprepossessing painting by the prolific Jan Van Goyen and leaves you thinking of it as a minor masterpiece.

Jan Van Goyen, Polder Landscape, 1644

"Even though we know that Van Goyen really had to work fast and with rubbish materials that didn't cost him very much money (he was so always in debt), there's a credible kind of convergence between what he's painting and how he's painting it. It's like a sketch. It's like an immediate note from his own vision. And everything that's kind of rough and raw and crude and clay-like and meagre about it actually makes you feel there. There are tops of houses - roofs - and you don't see anything else of the house. Why? Because they're actually below the waterline. This delivers a world - the silvery quality of the canals, a little boat floating past, and you think you're waking up and you can smell the peat turned over; it's a raw day in the middle of winter, and you're absolutely enveloped by the wind, the dark, lead coloured light. But this still, in it's scraped-away authenticity, is a kind of home."

No comments:

Post a Comment