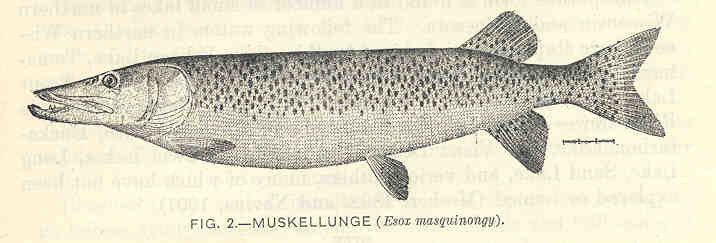

A while back on Caught by the River Rob St John reviewed Allan Burns' anthology Where the River Goes: The Nature Tradition in English Language Haiku (2013). He found that 'the most enjoyable bits of this fascinating but slightly frustrating book are the haiku themselves' and criticised the contrast between the introduction's bleak view of the environment with what is conveyed in the subsequent poems. Nevertheless, Burns' introduction does contain an interesting historical survey of the field, beginning in the sixties when nature-oriented poems were at the heart of the growing American haiku movement. From this early period he includes the work of James W. Hackett, O Mabson Southard and Nick Virgilio, whose highly concise ‘lily’ and ‘bass’ proved particularly influential. In the late sixties and early seventies nature haiku written by poets like John Wills and Robert Spiess became more specific - ‘instead of generalized fish and butterflies, they wrote with field-guide precision of muskellunge and mourning cloaks’.

In the seventies such subject matter became less central within English-language haiku writing, but something of a revival was sparked by the work of Charles B. Dickson, a retired journalist who produced a significant body of work before his death in 1991. Among this newer generation Wally Swist and Bruce Ross (compiler of The Haiku Moment) have been particularly devoted to nature-oriented haiku. Poets of the mid-to late-nineties represent a third generation, often publishing via the internet. Burns highlights the work of Carolyn Hall (editor of a journal that focused on nature poetry, Acorn), John Martone (whose work resembles the minimalist poetry of Creeley and Corman) and the British poet John Barlow, whose Snapshot Press published this book. I am embedding below a science animation produced in 2012 by Rob St. John that includes haiku by John Barlow which suggests how this writing is now being combined in new ways with sounds and images.

In his introduction Burns says that he has included mainly ‘type one’ haiku that refer exclusively to nature; type two haiku relate to both people and nature whilst type three are exclusively human-oriented. This typology was devised by George Swede in 1992 and he estimated that the split between these approaches in English language haiku was about 20:60:20. Burns calculates that by 2013 pure nature haiku had become rarer, so that the split was more like 13:67:20. ‘Undeniably, haiku in recent years has witnessed a kind of anthropocentric creep that mirrors an accelerating alienation of humans from the natural world.’ He contrasts this with classical haiku: apparently about 90% of Fukuda Chiyo-ni's were on nature and many of Basho’s have no direct sign of humanity, although of course they can always be read metaphorically in terms of human thought and emotions. I'd be interested to know how many 'type one' nature haiku suggest a whole landscape, by implying distance (birds on a lake, mountain mist) or uniting near and far (pool, moon). Perhaps they all do and it is just a question of how far we are willing to imagine what is left unsaid.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Chiyo-ni standing beside a well, mid 1840s

No comments:

Post a Comment