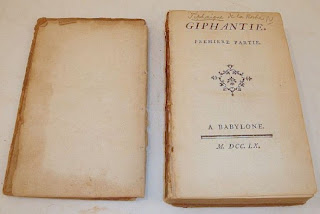

The first description of a landscape photograph was written in 1760, almost eighty years before the invention of photography. In Giphantie, Charles-François Tiphaigne de la Roche relates the experiences of a traveler in the land of Giphantia, a fertile place in the centre of Africa 'given to the elementary spirits the day before the Garden of Eden was allotted to the parent of mankind.' After seeing various wonders he is led by the Prefect of Giphantia into a subterranean hall, 'not much adorned', but with a window opening out onto 'a sea which seemed to me to be about a quarter of a mile distant. The air, full of clouds, transmitted only that pale light which forbodes a storm: the raging sea ran mountains high, and the shore was whitened with the foam of the billows which broke on the beach.' Astonished to see the ocean in the center of Africa, the traveler rushes forward to put his head out of the window, but knocks his head 'against something that felt like a wall. Stunned with the blow, and still more with so many mysteries, I drew back a few paces.' His guide explains: 'That window, that vast horizon, those thick clouds, that raging sea are all but a picture.' And the means by which this light painting was made can be read now as a remarkable anticipation of the photographic process:

'The elementary spirits (continued the Prefect), are not so able painters as naturalists; thou shalt judge by their way of working. Thou knowest that the rays of light, reflected from different bodies, make a picture and paint the bodies upon all polished surfaces, on the retina of the eye, for instance, on water, on glass. The elementary spirits have studied to fix these transient images: they have composed a most subtile matter, very viscous, and proper to harden and dry, by the help of which a picture is made in the twinkle of an eye. They do cover with this matter a piece of canvas, and hold it before the objects they have a mind to paint. The first effect of the canvas is that of a mirrour; there are seen upon it all the bodies far and near whose image the light can transmit. But what the glass cannot do, the canvas, by means of the viscous matter, retains the images. The mirrour shows the objects exactly; but keeps none; our canvases show them with the same exactness, and retains them all. This impression of the image is made the first instant they are received on the canvas, which is immediately carried away into some dark place; an hour after, the subtile matter dries, and you have a picture so much the more valuable, as it cannot be imitated by art nor damaged by time. We take, in their purest source, in the luminous bodies, the colours which painters extract from different materials, and which time never fails to alter. The justness of the design, the truth of the expression, the gradation of the shades, the stronger or weaker strokes, the rules of perspective, all these we leave to nature, who, with a sure and never-erring hand, draws upon our canvases, images which deceive the eye, and make reason to doubt whether, what are called real objects, are not phantoms which impose upon the sight, the hearing, the feeling, and all the senses at once.'

(anonymous English translation 1761)