Sundial from St Buryan Church, Cornwall

Source: Wikimedia Commons

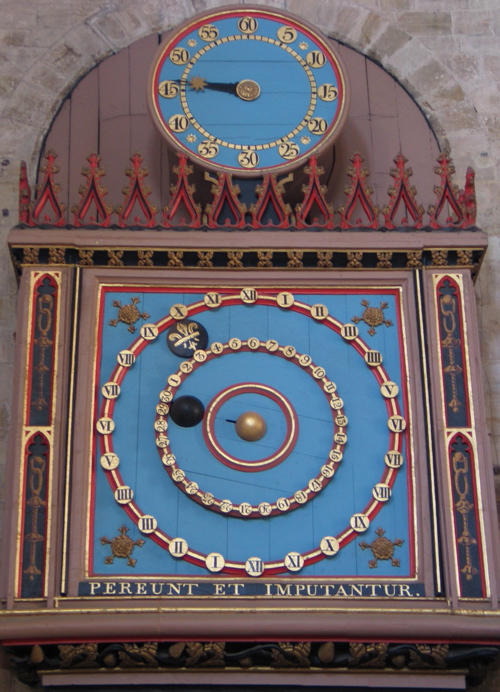

Martial dealt with the passing of time in a poem in praise of his friend, Julius Martial (5.20). Instead of having to spend time on 'frowning lawsuits and the gloomy Forum' he imagines their days devoted to living well and spending time with books. 'As it is now, neither of us lives for his own benefit; each of us can feel his best days slipping away and leaving us behind. They're gone, they've been debited from our account.' That line - bonosque soles effugere atque abire sentit, qui nobis pereunt et imputantur - inspired a fashion for carving the phrase Pereunt et imputantur onto sundials. I've included here a couple of examples. It is tempting here to digress onto the fascinating topic of sundial mottoes, but I will refer you instead to an Atlas Obscura article (here) and return to the poetry of Martial.

Sundial from Exeter Cathedral

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Even those of us who enjoy living in busy capital cities sometimes long for a more peaceful and beautiful environment. Martial wrote (6.64) admiringly of the home of his friend Julius Martial, sited well above the streets of Rome, on the Janiculan Hill, a place 'more blissful than the gardens of the Hesperides'. Here is a late 19th century public domain translation of the next few lines:

Secluded retreats are spread over the hills, and the smooth summit, with gentle undulations, enjoys a cloudless sky, and, while a mist covers the hollow valleys, shines conspicuous in a light all its own. The graceful turrets of a lofty villa rise gently towards the stars. Hence you may see the seven hills, rulers of the world, and contemplate the whole extent of Rome, as well as the heights of Alba and Tusculum, and every cool retreat that lies in the suburbs...It is pleasing to think that Martial was able to enjoy a pleasant garden in his retirement. The twelfth book of Epigrams was written in Spain and one of its poems (12.31) describes a retreat apparently gifted by his patron and mistress, Marcella.

This grove, these fountains, this interwoven shade of the spreading vine; this meandering stream of gurgling water; these meadows, and these rosaries which will not yield to the twice-bearing Paestum; these vegetables which bloom in the month of January, and feel not the cold; these eels that swim domestic in the enclosed waters; this white tower which affords an asylum for doves like itself in colour; all these are the gift of my mistress; Marcella gave me this retreat, this little kingdom, on my return to my native home after thirty-five years of absence. Had Nausicaa offered me the gardens of her sire, I should have said to Alcinous, "I prefer my own."

No comments:

Post a Comment