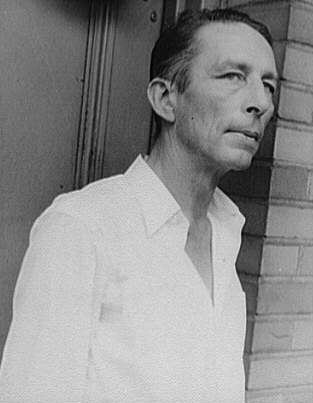

Robinson Jeffers' Hawk Tower, Tor House, Carmel

These criticisms echo those made at various times of Robinson Jeffers, the poet cited by Dark Mountain as a key inspiration, who advocated a philosophy of 'inhumanism' and opposed US involvement in the war - 'the fever-dreams of decaying Europe'. Addressing the tower he built at Carmel, he wrote "look, you gray stones / Civilization is sick: stand awhile and be quiet and drink, the sea-wind, you will survive / Civilization." This poem, 'Pearl Harbor', and others in his 1948 book The Double Axe provoked a disclaimer from his publishers and many hostile reviews. The Dark Mountain Manifesto acknowledges that Jeffers' reputation has suffered: 'today his work is left out of anthologies, his name is barely known and his politics are regarded with suspicion. Read Jeffers’ later work and you will see why. His crime was to deliberately puncture humanity’s sense of self-importance. His punishment was to be sent into a lonely literary exile from which, forty years after his death, he has still not been allowed to return.'

Robinson Jeffers may not be as well regarded now as he was eighty years ago, but his poems are still read and 'Carmel Point' appears in two recent anthologies of environmental poetry, Earth Shattering and Wild Reckoning. His inhumanism in this poem is not too extreme: 'we must unhumanize our views a little', he says. 'This beautiful place defaced with a crop of suburban houses— / How beautiful when we first beheld it, / Unbroken field of poppy and lupin walled with clean cliffs.' Jeffers is reassured that the landscape 'knows the people are a tide / That swells and in time will ebb, and all / Their works dissolve.' This theme of ecofatalism recurs in many Jeffers poems. In his book Ecocriticism Greg Garrard draws a connection between Jeffers (along with Lawrence and Nietzsche) and the more extreme biocentric beliefs espoused by some radical environmentalists. He also quotes Gary Snyder, who, though influenced by Jeffers, complains that his 'tall cold view' does not seem to have room for 'the inhuman beauty / of parsnips or diapers, the deathless / nobility at the core of all ordinary things.'

I think it is possible to agree with Snyder without wishing to read too many poems about diapers (having had six years of them I am thoroughly acquainted with their deathless nobility). Jeffers had two sons, and wrote 'I shall die, and my boys / Will live and die, our world will go on through its rapid agonies of change and discovery; this age will die.' This poem also illustrates the way Jeffers could write about the Californian landscape: 'we stayed the night in the pathless gorge of Ventana Creek, up the east fork. / The rock walls and the mountain ridges hung forest on forest above our heads, maple and redwood, / Laurel, oak, madrone, up to the high and slender Santa Lucian firs that stare up the cataracts / Of slide-rock to the star-color precipices...' For more on Jefferson and landscape you can browse the archives of the Jeffers Studies site: see for example 'Robinson Jeffers and the California Sublime', 'Robinson Jeffers' California Landscape and the Rhetoric of Displacement', 'The Essential landscape: Jeffers among the photographers' and three articles on Jeffers, geology and rocks. Of particular relevance to this post is Peter Quigley's article 'Carrying the Weight: Jeffers’s Role in Preparing the Way for Ecocriticism'.

I think it is possible to agree with Snyder without wishing to read too many poems about diapers (having had six years of them I am thoroughly acquainted with their deathless nobility). Jeffers had two sons, and wrote 'I shall die, and my boys / Will live and die, our world will go on through its rapid agonies of change and discovery; this age will die.' This poem also illustrates the way Jeffers could write about the Californian landscape: 'we stayed the night in the pathless gorge of Ventana Creek, up the east fork. / The rock walls and the mountain ridges hung forest on forest above our heads, maple and redwood, / Laurel, oak, madrone, up to the high and slender Santa Lucian firs that stare up the cataracts / Of slide-rock to the star-color precipices...' For more on Jefferson and landscape you can browse the archives of the Jeffers Studies site: see for example 'Robinson Jeffers and the California Sublime', 'Robinson Jeffers' California Landscape and the Rhetoric of Displacement', 'The Essential landscape: Jeffers among the photographers' and three articles on Jeffers, geology and rocks. Of particular relevance to this post is Peter Quigley's article 'Carrying the Weight: Jeffers’s Role in Preparing the Way for Ecocriticism'.

3 comments:

apart from Anne Enright's reference to baby bottoms smelling lightly of Camembert, I don't know of any nappy poetry or prose... parsnips could be a worthy subject, perhaps Jane Grigson's recipe for curried parsnip soup is the best example

Mrs P

Having followed the links and read the manifesto, I'm struck by the disparity between the severity of the diagnosis and the mildness of the proposed remedy -- "bathos" is probably the word.

What are the chances of anything so rhetorical and Boy Scout-ish averting global disaster or inheriting what is left of the world when Tesco and BP have finished with it?

The opposition and caution are understandable -- sadly, if the past is any guide, it often seems that a preference for "nature" over "civilisation" can lead in bad directions -- eugenics, racial politics, anti-democratic "strong leaders"... There's a package there (I expect a lot of Survivalists support Palin and the Tea Party).

But maybe these guys are different? Let us know what you make of them.

Mike

Thanks Lisa - no poetry could live up to your roast parsnips.

Mike C - we discussed the Manifesto at the Values of Environmental Writing Research Network event in Glasgow, and it would be fair to say that there were a range of views. Some responded to the urgency of the apocalyptic message, others found it a bit lame - something of a re-hash American deep ecology. I think none of us had a very clear view of exactly what kind of art was being advocated. But it did get us talking...

Post a Comment