Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Hunters in the Snow (Winter), 1565

According to Robert D. Denham's, Poets on Paintings: A Bibliography (2010), Brueghel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus has been the subject of at least sixty-three poems. In addition to the well-known ones by W. H. Auden and William Carlos Williams, there have been others by, for example, Dannie Abse, Gottfried Benn, Allen Curnow, Michael Hamburger and Philip Whalen. However, it is clear from this bibliography that Bruegel's Hunters in the Snow has also drawn an interesting range of writers: Williams again, John Berryman, Anne Stevenson, Walter De La Mare (and they keep coming: the new edition of Granta has one by Andrew Motion). Berryman considers the hunters frozen at a moment in history and Stevenson imagines their moment of arrival as they 'pull / off their caked boots, curse the weather / slump down over stoups. . .' Williams describes Bruegel's artistry, beginning matter-of-factly - 'The over-all picture is winter / icy mountains / in the background...' - and ending by noting the way he chose 'a winter-struck bush for his / foreground to / complete the picture.' Walter De La Mare begins in ekphrasis, starting like Williams with the distant landscape: 'Jagg'd mountain peaks and skies ice-green / Wall in the wild, cold scene below'. His poem ends on a mysterious note:

But flame, nor ice, nor piercing rock,

Nor silence, as of a frozen sea,

Nor that slant inward infinite line

Of signboard, bird, and hill, and tree,

Give more than subtle hint of him

Who squandered here life's mystery.

William Carlos Williams' Bruegel poems appeared posthumously in Pictures from Brueghel and other poems (1962). Denham's bibliography lists other examples of poets who have written extended sequences or whole volumes devoted to painting. Perhaps the most prominent of these is, R. S. Thomas, whose ‘Impressions’ in Between Here and Now (1981) include landscapes by Monet, Pissaro and Gauguin. One of them is devoted to Cézanne’s The Bridge at Maincy which was featured in one of my earlier posts here. There have also been whole books devoted to single artists, such as Turner and Monet. Robert Fagles, best known for his translations of Homer, published one of these in 1978: I, Vincent: Poems from the Pictures of Van Gogh.

Denham has compiled a long list of individual poems but my impression on leafing through it is that relatively few of them have been about independent, unpeopled landscape paintings. It is though unsurprising to find that writers have been more attracted to paintings suggesting drama, complexity or ambiguity - in the last century artists like Edward Hopper and Marc Chagall were common subjects. Even in paintings where landscape dominates the composition, people exert a fascination (Czeslaw Milosz, reflecting on a painting by Salvator Rosa, writes of 'figures on the other shore tiny, and in their activities mysterious.') Simple unadorned description of a what a painting shows is rare, although William Carlos Williams, advocate of 'no ideas but in things', does this in 'Classic Scene', recreating in words Charles Sheeler's 1931 view of the new Ford plant near Detroit.

Although Denham explicitly excludes from the book examples of reverse ekphrasis (paintings inspired by poems), the variety of poems listed invite speculation on ways of combining writing, painting and landscape. It occurs to me that you could use a kind of algebra (which would need to allow for poets painting and painters writing poems): if, say, the combination of a poet, P, writing, w, about landscape, L, gives rise to a landscape poem, P.w(L), and, similarly, a landscape painting arises from an artist creating a landscape, A.c(L), then a poet writing about a landscape painting is P.w(A.c(L)). Reverse ekphrasis involving a landscape poem would then be A.c(P.w(L)). Here's an example of something more complicated. John Hollander (whose visual poetry I have mentioned here before) wrote a poem about another Charles Sheeler painting, The Artist Looks at Nature (1943). Sheeler's painting is a kind of landscape - there are grassy slopes and the walls of battlements - but it also contains an artist working on a canvas. And though apparently painting from nature, his canvas depicts the interior of a studio. Thus Hollander's poem could be represented as P.w(A.c(L+A.c(L'))).

| Being thirsty, | |

| I filled a cup with water, | |

| And, behold!—Fuji-yama lay upon the water, | |

| Like a dropped leaf! |

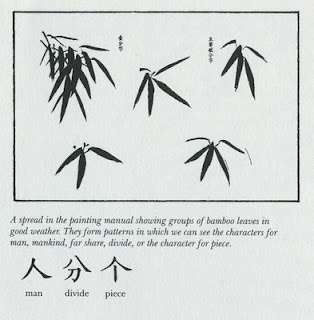

This is Amy Lowell's imagist poem inspired by Hokusai's 'Hundred Views of Mt Fuji'. Denham's book doesn't really get into the subject of Japanese or Chinese poetry about landscape painting, although he does mention Su Shi's ‘Two Poems on Guo Xi’s Autumn Mountains in Level Distance'. In Chinese art where the 'three perfections' (poetry, calligraphy, painting) are combined in one object, we are often not sure what came first: the poem or the painting. Where artist and writer are one and the same, my algebraic distinctions would be meaningless. I will end here with part of another poem inspired by a Hokusai, 'Lightning Storm on Fuji' by Howard Nemerov.

Katsushika Hokusai, Rainstorm Beneath the Summit, c. 1830

... the serene mountain rises

And falls in a clear cadence. The snowy peak,

Where the brown foliage falls away, is white

As the sky behind it, so that line alone

Seems to be left, and the hard rock become

Limpid as water, the form engraved on glass.

There at the left, hanging in empty heaven,

A cartouche with written characters proclaims

Even to such as do not know the script

That this is art, not nature. ...

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/800px-Pieter_Bruegel_the_Elder_-_Hunters_in_the_Snow_(Winter)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)