I have been immersed in Athanasius Kircher's Theatre of the World, a (literally) wonderful and wittily-written book about the great seventeenth century polymath. Its author Joscelyn Godwin is something of a polymath himself but has written mainly about music and the occult (he has featured on this blog before as translator of the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili). The book discusses Kircher's inventions, some of which were housed in his museum at the Jesuit Roman College, and covers his extensive writings in Latin on language, religion, geography, science, music and many other topics. There have been numerous books on Kircher in recent years and Godwin was the author of one of the first of these (in 1979); his aim in this subsequent volume was to focus attention on Kircher's illustrations. These, in contrast to the some of the original texts, 'have a quality of ingenuity and strangeness that are particular to his century, and of singular appeal to ours.'

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Tower of Babel, c. 1563

The engravers worked from Kircher's designs which were either his own inventions or adaptations from other sources, sometimes mere sketches sent by travellers and correspondents. The Tower of Babel reproduced on the cover of this book comes from Turris Babel (1679) and was obviously inspired by the famous Breugel painting. It was actually drawn by Coenraet Decker and engraved by Lievin Cruyle. The tower differs from Bruegel's in having 'a system of crossing ramps from one of Kircher's favourite ancient buildings, the Temple of Fortune in Praeneste'. Bruegel's tower looks like it is being built in the Flemish countryside, but Kircher's is surrounded by ancient monuments, including numerous pyramids and obelisks, subjects he treated extensively in Oedipus Aegyptiacus (1652-4) and Obeliscus Aegyptiacus (1666). His fascination with the obelisks of Rome made me want to revisit the city and spend a day tracking them all down, from the Flaminian obelisk now in the Piazza del Popolo to the Sallustian obelisk at the top of the Spanish Steps.

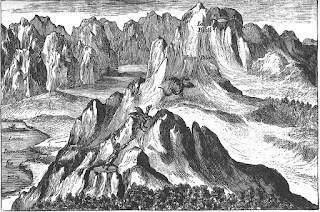

Athanasius Kircher, The Earthly Paradise, from Arca Noë (1675)

Kircher's depictions of ancient sites as they might once have appeared range from the Roman villas that he could visit around Tivoli to places for which he had to rely on ancient texts: the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the citadel of Atlantis and the Garden of Eden (above). For China Illustrata (1667) he made use of the Travels of Marco Polo and more recent information sent back by his fellow Jesuits. It includes depictions of the Mountain of Fe, shaped either naturally or artificially (Kircher puts arguments for both possibilities) into the resemblance of a Chinese god; the Seven Peaks, which seem to correspond to the configuration of the Great Bear; and Lake Chin, on the surface of which float waterlilies and, more strangely, a child on a piece of wood, the sole survivor of a city destroyed by an earthquake. In this volume Kircher also illustrates Dragon and Tiger Mountain with the creatures themselves about to fight each other. Although sceptical of some mythical creatures, Kircher believed in the existence of dragons, even in Europe. 'It may surprise the reader', Joscelyn Edwards observes, 'to learn that dragons were nowhere more prevalent than in Switzerland.' The idea of a dragon on Mt Pilatus terrorising Lucerne inevitably recalled for me Smaug's destruction of Lake-town in The Hobbit.

Athanasius Kircher, Dragons of Lake Lucerne, from Mundus Subterraneous (1664-78)

Some of Kircher's most famous 'landscape' drawings are in Mundus Subterraneus where they illustrate his theories of geography, geology and the movement and actions of fire and water. His notion of the hydrological cycle required underground mountain reservoirs and subterranean channels connecting the seas. At the North and South Poles, as yet unknown, he imagined the global flow of water governed by a vast whirlpool and spring. I have included here before his image of Mt Vesuvius, a volcano Kircher explored himself. Inside the crater he 'perceived the groaning and shaking of the dreadful mountain, the inexplicable stench, the dark smoke mixed with globes of fire which the bottom and sides of the mountain continuously vomited forth from eleven different places, forcing me at times to vomit it out myself...'

Athanasius Kircher, The Loudspeaker System at Mentorella, from Phonurgia Nova (1673)

Kircher wrote a topographical study, Latium (1671) about the region around Rome. He was particularly drawn to the sanctuary of Mentorella, which he helped preserve, and it was here that he performed some of his acoustic experiments, with loudspeakers directed at the surrounding hills (see above). This sacred place had witnessed the conversion of St Eustace, when the figure of Christ appeared between the antlers of a stag (see illustration below). Kircher's book Historia Eustachio-Mariana (1665) contains a memorable description of his discovery of the sanctuary and I will end this post with it. As Joscelyn Godwin remarks, 'the eighteenth century did not invent the Sublime, nor the Romantic era the melancholy attraction of ruined choirs.'

'In 1661, while I was exploring the mountains of Polano and Praeneste, I started in Tivoli and passed through wild mountains and rocks. Around noon I came to a horrid, solitary place, hemmed round with rocks like a crown. It really was a place filled with horror, where the stony pyramids seemed to scrape the heavens, and, falling from hanging rocks in formidable vortices, seemed to express infernal motion. In the midst of all this, among dark trees and rocks, I came across the remnants of a roof: it was a church, all but collapsed. But how could there be a church in this place of terror and solitude? I asked the guide. Going in I saw the pictures and sculptures of the saints. Everything breathed the devotion of ancient piety.'

Athanasius Kircher, The Conversion of St. Eustace, from Latium (1671)

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/1280px-Pieter_Bruegel_the_Elder_-_The_Tower_of_Babel_(Vienna)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/800px-Pieter_Bruegel_the_Elder_-_Hunters_in_the_Snow_(Winter)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)