Thursday, April 30, 2009

A Sleepwalk on the Severn

I have just read Alice Oswald's new book, A Sleepwalk on the Severn. I've written here before about her earlier river poem, Dart, a work which seems to gather new admirers with every passing year (Germaine Greer apparently thinks Alice Oswald should be the next poet laureate). Dart, according to The Observer, 'was the result of three years of locally recorded conversations and her new work, A Sleepwalk on the Severn, is likewise grounded in footslogging research. The poem gives voice to a slippery crew of real river folk, among them a birdwatcher, a vicar and an articled clerk, who haunt the Severn estuary. Sleepwalk is a weird dream of a poem, set at night over five different phases of the Moon. Though a note tartly informs the reader that "this is not a play", the work it most often recalls is Under Milk Wood, with its counterpointed voices and ardent attentiveness to place.' I found it much less accessible than Dart and will need to give it some time to sink in I think. You can hear some of it at the end of a slightly stilted Woman's Hour interview, and read some lines on the website of Jeanette Winterson (another Oswald fan).

Sleepwalk was commissioned by Gloucestershire County Council. I have talked here before about art that is commissioned to consider particular landscapes, such as the photographs (Jason Orton) and text (Ken Worpole) of 350 Miles, An Essex Journey. It is easy to see how money could be found for books that generate interest by exploring aspects of a locality, or for site specific artworks that draw new visitors. And in these days of 'relational aesthetics', landscape art which invites participation or involves local people should be even more attractive. Sleepwalk, like Dart, is a collage that uses real voices and actual history (in this it is partly in the tradition of earlier poems of place, like Paterson, or Charles Olson's Maximus Poems which centre on Gloucester, Massachusettes). The poem is also being given back to the people of the Severn catchment in the form of a theatre piece that is on tour this spring.

Labels:

Alice Oswald,

rivers,

the moon

Location:

River Severn, Gloucsetershire

Saturday, April 25, 2009

Gentle airs and murmuring brooks

Beethoven wrote his Pastoral Symphony in 1807-8, but as Elizabeth Schwarm Glesner writes on the Classical Music Pages, 'this was certainly not the first time that nature found its way into concert music. Baroque composers were fond of hunting scenes and bird calls. Leopold Mozart produced a bit of fluff called A Musical Sleighride, complete with barking dogs, and Haydn's The Seasons, which dates from 1801, is filled with scenes from country life. Although these examples are familiar, one probable influence on Beethoven is often overlooked. In 1784, the publisher Bossler issued a set of piano trios by Beethoven. He advertised the works in the newspaper, and, on the same page, listed another composition, also published by Bossler, a five-movement symphony by the now-forgotten Justin Heinrich Knecht, a work entitled A Musical Portrait of Nature. Each movement of that symphony carried a descriptive title, remarkably similar to those used a dozen years later by Beethoven, who also made the same unusual choice of five movements. Beethoven almost certainly knew of this precedent for his own symphony and for his titles, but, since the secret to successful plagiarism is to be better known than your source, Beethoven was never questioned.'

Beethoven's five movements were (in English translation):

(1) Awakening of cheerful feelings upon arrival in the country

(2) Scene by the brook

(3) Happy gathering of country folk

(4) Thunderstorm; Storm

(5) Shepherd's song; cheerful and thankful feelings after the storm

An article on the Bach Cantatas site, explains that the earlier Knecht composition, Le Portrait Musical de la Nature, was 'a grand symphony for two violins, viola and bass, two flutes, two oboes, bassoons, horns, trumpets and drums ad lib., in which is expressed:

(1) A beautiful country, the sun shining, gentle airs and murmuring brooks; birds twitter, a waterfall tumbles from the mountain, the shepherd plays his pipe, the shepherdess sings, and the lambs gambol around.

(2) Suddenly the sky darkens, an oppressive closeness pervades the air, black clouds gather, the wind rises, distant thunder Is heard, and the storm approaches.

(3) The tempest bursts in all Its fury, the wind howls and the rain beats, the trees .groan and the streams rush furiously.

(4) The storm gradually goes off, the clouds disperse and the sky clears.

(5) Nature raises its joyful voice to heaven in songs of gratitude to the Creator (a hymn with variations).'

Beethoven's five movements were (in English translation):

(1) Awakening of cheerful feelings upon arrival in the country

(2) Scene by the brook

(3) Happy gathering of country folk

(4) Thunderstorm; Storm

(5) Shepherd's song; cheerful and thankful feelings after the storm

An article on the Bach Cantatas site, explains that the earlier Knecht composition, Le Portrait Musical de la Nature, was 'a grand symphony for two violins, viola and bass, two flutes, two oboes, bassoons, horns, trumpets and drums ad lib., in which is expressed:

(1) A beautiful country, the sun shining, gentle airs and murmuring brooks; birds twitter, a waterfall tumbles from the mountain, the shepherd plays his pipe, the shepherdess sings, and the lambs gambol around.

(2) Suddenly the sky darkens, an oppressive closeness pervades the air, black clouds gather, the wind rises, distant thunder Is heard, and the storm approaches.

(3) The tempest bursts in all Its fury, the wind howls and the rain beats, the trees .groan and the streams rush furiously.

(4) The storm gradually goes off, the clouds disperse and the sky clears.

(5) Nature raises its joyful voice to heaven in songs of gratitude to the Creator (a hymn with variations).'

Monday, April 20, 2009

The End of Summer

When I think of ECM records I tend to imagine covers showing snowy landscapes, like this one. This is probably because I tend to associate ECM with north European composers and performers, Jan Garbarek for instance, whose music often gets described as 'glacial' and 'icy'. In fact the covers and music are very varied. Landscape imagery is usually used when the title seems to demand it, like this shadow falling over the sea for Julia Hulsmann's recent album, The End of Summer.

A couple more examples from ECM's New Series: Erkki-Sven Tüür's Exodus shows a sunlit road and, in a similar vein, it is no surprise to see a work by his fellow Estonian Arvo Pärt's entitled 'Misterioso' illustrated with sun breaking through clouds.

A couple more examples from ECM's New Series: Erkki-Sven Tüür's Exodus shows a sunlit road and, in a similar vein, it is no surprise to see a work by his fellow Estonian Arvo Pärt's entitled 'Misterioso' illustrated with sun breaking through clouds.

Reading a discussion thread on ECM cover art I see that someone is complaining about the fashion for blurred photographs on recent releases. Jon Hassell's return to the ECM label, Last night the moon came dropping its clothes in the street (the title is taken from a Rumi poem) exemplifies this. More Gerhard Richter than Caspar David Friedrich, it has a bit more edginess than one might expect from an 'ECM landscape'.

Sunday, April 19, 2009

The Drowned World

The death of J. G. Ballard is very sad news - a writer I've loved since reading his disaster novels and short stories as a teenager.

From the many riches of the Ballardian website, I'm linking here to a piece on Flooded London, with some great photos by Squint/Opera and a quotation from The Drowned World (1962):

'The bulk of the city had long since vanished, and only the steel-supported buildings of the central commercial and financial areas had survived the encroaching flood waters. The brick houses and single-storey factories of the suburbs had disappeared completely below the drifting tides of silt. Where these broke surface giant forests reared up into the burning dull-green sky, smothering the former wheatfields of temperate Europe and North America. Impenetrable Mato Grossos sometimes three hundred feet high, they were a nightmare world of competing organic forms returning rapidly to their Paleozoic past, and the only avenues of transit for the United Nations military units were through the lagoon systems that had superimposed themselves on the former cities. But even these were now being clogged with silt and then submerged...'

From the many riches of the Ballardian website, I'm linking here to a piece on Flooded London, with some great photos by Squint/Opera and a quotation from The Drowned World (1962):

'The bulk of the city had long since vanished, and only the steel-supported buildings of the central commercial and financial areas had survived the encroaching flood waters. The brick houses and single-storey factories of the suburbs had disappeared completely below the drifting tides of silt. Where these broke surface giant forests reared up into the burning dull-green sky, smothering the former wheatfields of temperate Europe and North America. Impenetrable Mato Grossos sometimes three hundred feet high, they were a nightmare world of competing organic forms returning rapidly to their Paleozoic past, and the only avenues of transit for the United Nations military units were through the lagoon systems that had superimposed themselves on the former cities. But even these were now being clogged with silt and then submerged...'

Wednesday, April 15, 2009

The Beth Chatto Gardens

The other week I finally got round to looking at the revamped Museum of Garden History in Lambeth (now called the Garden Museum). At first it is rather disconcerting - you pay your £6, step in and then look around - where has the museum gone? It is now upstairs on a sort of landing space, with the ground floor now a big empty area that can be used for talks (and presumably commercial events?) It is some years since I last went and I don't remember the permanent collection being very large, but now it seems so small it reminded me of the kind of museum you put together as a child (like Anne Fadiman's 'Serendipity Museum of Nature'). What they have, like the display on lawns above, is nice, but it barely touches the surface of such a large subject (and that's just lawns, let alone gardens...)

There is a new space for exhibitions and I looked round their Beth Chatto retrospective. Her garden in Essex, designed to work with the limitations of an 'unpromising landscape', is very close to my mother-in-law so I've been there several times (the photo below is from a few years ago). We've bought some of her plants for our modest patch here in Stoke Newington - artemisia ludoviciana, tiarella cordyfolia and omphalodes capadocia 'Cherry Ingram', which is out at the moment.

Geoff Manaugh, who writes the superb BLDBLOG, did an article on the new Garden Museum for Dwell. You can see from his photos how empty the building looks - although as the article says, it's all done very stylishly. I must get to a talk there... the museum's curator is Christopher Woodward who wrote the excellent In Ruins, so we can expect an interesting programme which should cover landscape topics (the schedule for spring and summer isn't announced yet). They have already been hosting a series of conversations with Tim Richardson and Noël Kingsbury, authors of Vista: The Culture and Politics of Gardens, and although these are not open to the public (invitation only) some of them are available as MP3s at Gardens Illustrated.

Tuesday, April 14, 2009

To the snow-covered island

There's a Tomas Tranströmer poem called 'From March 1979' that I was thinking of mentioning in the previous posting, but didn't because there seems to be a difference in the way it describes writing in the landscape. Tranströmer comes across tracks in the snow - a natural sign, rather than something that happens to remind the poet of linguistic signs. The poem starts with Tranströmer weary of words, 'words but no language'. He goes to a snow-covered island, which resembles unwritten pages, and in the tracks of the deer sees 'language but no words.'

In an article for Poetry Review Jay Parini says that 'this archetypal poem forms a tiny myth, describing a literal journey with symbolic dimensions, thus extending the metaphor in various directions. Most of us who read a good deal are sick of those “who come with words, words but no language.” This revulsion often propels a poem into being, as in Yeats’s “I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree.” One arrives in the land of silence: “Wilderness has no words.” The metaphor rapidly becomes a conceit, as the unprinted fields of snow become “unprinted pages.” The sleight of mind in the last stanza is, again, typical: Tranströmer deepens the image unexpectedly, giving a literal level – the deer’s footprints in the snow – and a range of associations, as we are left contemplating this “language without words” – which (in my own association) is akin to Chomsky’s Universal Grammar – which underlies speech, underwrites silence itself.'

In an article for Poetry Review Jay Parini says that 'this archetypal poem forms a tiny myth, describing a literal journey with symbolic dimensions, thus extending the metaphor in various directions. Most of us who read a good deal are sick of those “who come with words, words but no language.” This revulsion often propels a poem into being, as in Yeats’s “I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree.” One arrives in the land of silence: “Wilderness has no words.” The metaphor rapidly becomes a conceit, as the unprinted fields of snow become “unprinted pages.” The sleight of mind in the last stanza is, again, typical: Tranströmer deepens the image unexpectedly, giving a literal level – the deer’s footprints in the snow – and a range of associations, as we are left contemplating this “language without words” – which (in my own association) is akin to Chomsky’s Universal Grammar – which underlies speech, underwrites silence itself.'

Location:

Stockholm

Friday, April 10, 2009

A fugitive inscription on the pages of the earth

Sometimes I think that an ideal landscape poetry would be written by the landscape itself. How? Some examples from Philippe Jaccottet's poetry (see Under Clouded Skies & Beauregard and my earlier post): wind on water is 'a fugitive inscription on the pages of the earth,' darkness is 'thin and threatening ink', the flight of birds 'calligraphy in the sky'. Eugenio Montale is another poet who sees writing in nature - a translation of 'Quasi una Fantasia' by David Young reads 'with joy I’ll read the black / figures of the branches, stark against the white, / an esoteric alphabet'. Similarly, William Carlos Williams writes in 'The Botticellian Trees' of the thin letters that spell winter and the alphabet of trees. I'd be interested in other examples...

I'd also love to know more about Jean-Pierre Richard's Pages paysages (Mark Treharne mentions it in his introduction to Jaccottet's poems). Apparently it develops the idea of the page as a landscape, which would mirror the poems I've just mentioned... The book seems hard to get hold of even in French and I don't think it's been translated.

I'd also love to know more about Jean-Pierre Richard's Pages paysages (Mark Treharne mentions it in his introduction to Jaccottet's poems). Apparently it develops the idea of the page as a landscape, which would mirror the poems I've just mentioned... The book seems hard to get hold of even in French and I don't think it's been translated.

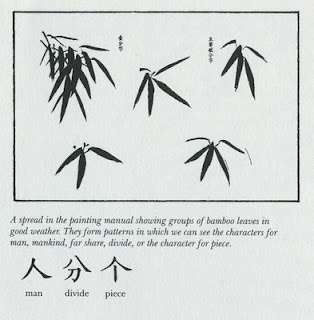

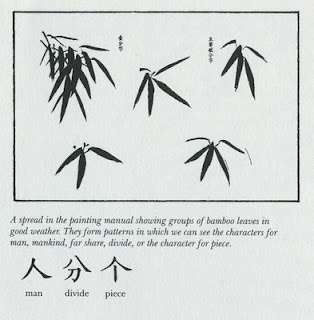

China: Empire of Living Symbols (see my previous post) includes an illustration that shows how close the pattern of leaves can come to writing. It comes from the famous Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, the first part of which was published in 1679. Calligraphy and painting seem almost to merge here and suggest the possibility of a kind of landscape art suspended somewhere between poetry and painting.

I'd also love to know more about Jean-Pierre Richard's Pages paysages (Mark Treharne mentions it in his introduction to Jaccottet's poems). Apparently it develops the idea of the page as a landscape, which would mirror the poems I've just mentioned... The book seems hard to get hold of even in French and I don't think it's been translated.

I'd also love to know more about Jean-Pierre Richard's Pages paysages (Mark Treharne mentions it in his introduction to Jaccottet's poems). Apparently it develops the idea of the page as a landscape, which would mirror the poems I've just mentioned... The book seems hard to get hold of even in French and I don't think it's been translated.China: Empire of Living Symbols (see my previous post) includes an illustration that shows how close the pattern of leaves can come to writing. It comes from the famous Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, the first part of which was published in 1679. Calligraphy and painting seem almost to merge here and suggest the possibility of a kind of landscape art suspended somewhere between poetry and painting.

Tuesday, April 07, 2009

Climbing Omei Mountain

China: Empire of Living Symbols is a book I've been recommending to anyone with even a passing interest in China. A collection of rather tired adjectives come to mind which don't really do it justice: charming, fascinating, beautiful. The book discusses the origins and evolution of all kinds of Chinese ideographs, but here I'm focusing on landscape. The cover of the book shows the characters for 'mountain' and 'water' - the smaller symbols are the early versions of these characters found on Shang dynasty bronzes, which resemble more closely the corresponding natural features. 'The character for water is the picture of a river with its currents, whirlpools, and sandbanks, as one sees when standing on the riverbank looking over the course of the river.' The character for mountain resembles China's sacred mountains - Taishan, Songshan and Huashan.

China: Empire of Living Symbols is a book I've been recommending to anyone with even a passing interest in China. A collection of rather tired adjectives come to mind which don't really do it justice: charming, fascinating, beautiful. The book discusses the origins and evolution of all kinds of Chinese ideographs, but here I'm focusing on landscape. The cover of the book shows the characters for 'mountain' and 'water' - the smaller symbols are the early versions of these characters found on Shang dynasty bronzes, which resemble more closely the corresponding natural features. 'The character for water is the picture of a river with its currents, whirlpools, and sandbanks, as one sees when standing on the riverbank looking over the course of the river.' The character for mountain resembles China's sacred mountains - Taishan, Songshan and Huashan.Cecilia Lindqvist juxtaposes the character for mountain written by the great painter-calligrapher Mi Fu (or Mi Fei) (1051-1107) with some of the mountains he painted. 'Despite the difference in technique, there is an unmistakable similarity between the character for mountain and the mountain peaks in the painting, not only in their outward form but most of all in the strength they convey.' Mi Fu and his son Mi Youren originated the cloudy mountain style of landscape painting in China.

The book discusses some other 'landscape' characters: 'island' which seems to derive from a picture of sandbanks in a river, 'valley' which looks like the opening to a valley, 'cliff' (included in Chinese compound characters) which clearly depicts a cliff, and 'rock' which seems to show a boulder that has fallen from a cliff.

The book discusses some other 'landscape' characters: 'island' which seems to derive from a picture of sandbanks in a river, 'valley' which looks like the opening to a valley, 'cliff' (included in Chinese compound characters) which clearly depicts a cliff, and 'rock' which seems to show a boulder that has fallen from a cliff.It is all very reassuring to a reader like me who knows little about the Chinese language but whose imagination was caught long ago by Ernest Fenollosa's The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry and the 'ideogrammic' poems of Ezra Pound that it influenced. There have been many articles explaining how wrong Fenollosa was, e.g. in giving the impression that many Chinese characters have pictorial origins. Lindqvist's book, whilst clearly focusing on the primitive characters which have an iconic quality, shows how these occur throughout the whole of Chinese culture.

Fenollosa's notion that Chinese characters contain an inner energy and convey strong verbal actions may have been fanciful, but there is still something very appealing in the idea that a poem in Chinese can relate directly to what it signifies (a mountain) through the shape of a signifier, and that such a poem can be written out with all the artistry of a landscape painting.

There are numerous Chinese mountain poems on a site I've mentioned before, Mountain Songs, such as 'Climbing Omei Mountain' by Li Bai (Li Po). The character written by Mi Fu and reproduced above can be seen here in the poem's title,

and Li Bai's description of Omei mountain resembles a 'cloudy mountain' painting: 'The blue mists support me / the sky opens out; / Colors commingle / is it a painted picture?'

and Li Bai's description of Omei mountain resembles a 'cloudy mountain' painting: 'The blue mists support me / the sky opens out; / Colors commingle / is it a painted picture?'

Location:

Mount Emei, China

Friday, April 03, 2009

Olive trees

D. H. Lawrence was not 'profoundly interested in landscape'. In a 1929 essay 'Introduction to these pictures', he praises artists like Titian, Velazquez and Rembrandt, who depict real people, and criticises lesser painters like Reynolds and Gainsborough, for whom the clothes were more important than the body. He then goes on to say that 'landscape seems to be meant as a background to an intenser vision of life, so to my feeling painted landscape is background with the real subject left out... It doesn't call up the more powerful responses of the human imagination, the sensual, passional responses... It is not confronted with any living procreative body.'

The fact that landscape painting avoids dealing with the body is the reason, according to Lawrence, why the English have excelled at it. 'It is a form of escape for them, from the actual human body they so hate and fear, and it is an outlet for their perishing aesthetic desires... It is always the same. The northern races are so innerly afraid of their own bodily existence... that all they cry for is an escape. And, especially, art must provide that escape.' This would be one way of interpreting the northern 'Romantic tradition' of landscape painting (which I've discussed here before). And whilst these comments seem almost stereotypically Lawrentian, they point to a real concern that landscape art can represent a refusal to engage with humanity - an accusation that could still be levelled at land artists like Richard Long, walking in the wilderness.

Lawrence goes on to describe the impressionists' escape into light and then the post-impressionists who 'still hate the body - hate it. But, in a rage, they admit its existence, and paint it as huge lumps, tubes, cubes, planes, volumes, spheres, cones, cylinders, all the "pure" or mathematical forms of substance. As for landscape, it comes in for some of the same rage. It has also suddenly gone lumpy. Instead of being nice and ethereal and non-sensual, it was discovered by van Gogh to be heavily overwhelmingly sensual.'

The fact that landscape painting avoids dealing with the body is the reason, according to Lawrence, why the English have excelled at it. 'It is a form of escape for them, from the actual human body they so hate and fear, and it is an outlet for their perishing aesthetic desires... It is always the same. The northern races are so innerly afraid of their own bodily existence... that all they cry for is an escape. And, especially, art must provide that escape.' This would be one way of interpreting the northern 'Romantic tradition' of landscape painting (which I've discussed here before). And whilst these comments seem almost stereotypically Lawrentian, they point to a real concern that landscape art can represent a refusal to engage with humanity - an accusation that could still be levelled at land artists like Richard Long, walking in the wilderness.

Lawrence goes on to describe the impressionists' escape into light and then the post-impressionists who 'still hate the body - hate it. But, in a rage, they admit its existence, and paint it as huge lumps, tubes, cubes, planes, volumes, spheres, cones, cylinders, all the "pure" or mathematical forms of substance. As for landscape, it comes in for some of the same rage. It has also suddenly gone lumpy. Instead of being nice and ethereal and non-sensual, it was discovered by van Gogh to be heavily overwhelmingly sensual.'

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)