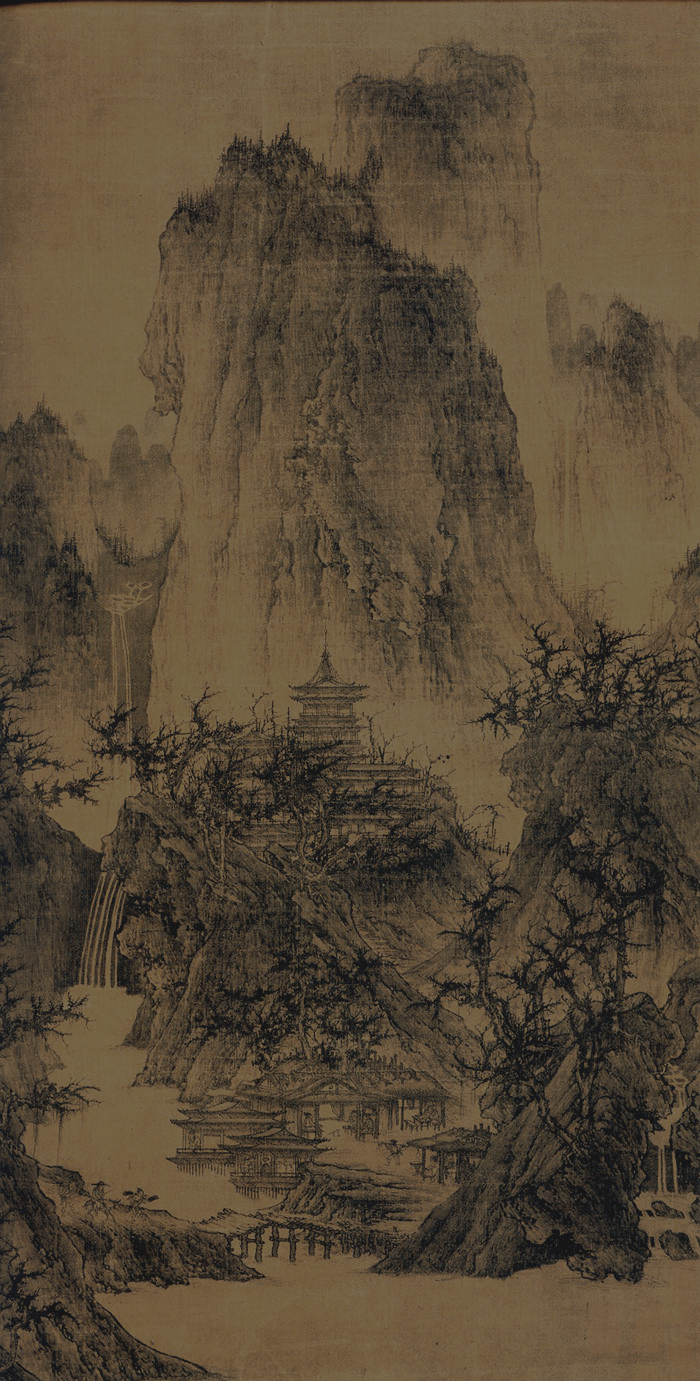

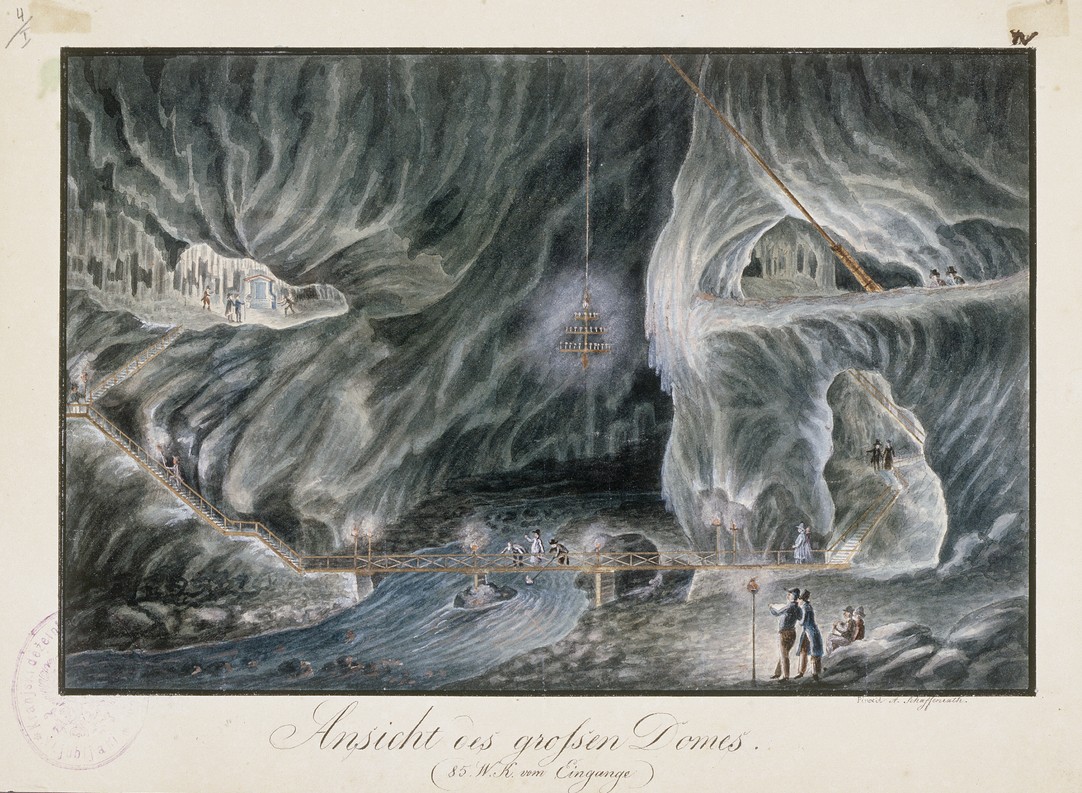

Josef Kuwasseg, The Period of the Muschelkalk, c. 1850

Source: The Universalmuseum Joanneum

This remarkable vision of a prehistoric shoreline was painted by an Austrian landscape painter, Josef Kuwasseg (1799-1859). The paleobotonist Franz Xaver Unger who commissioned a series of lithographs from him said that such paintings had "that mysterious charm which belongs to the contemplation of the distant past, and to the memory of our dreams." This painting is reproduced in a sumptuously illustrated (and pricey) new book that I was given for Christmas, Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past. It traces the ways artists have portrayed scenes from the distant past over the last two centuries, incorporating stylistic elements from Romanticism, Impressionism, Fauvism and Art Nouveau. The author, New York art critic Zoë Lescaze, also reads into these old pictures of dinosaurs, flying reptiles and neanderthals the politics of paleontology (ongoing battles between rival scientists) and our wider anxieties about war and apocalypse.

Josef Kuwasseg, Primeval world, c. 1850

Source: The Universalmuseum Joanneum

I have referred briefly here before to paleoart, in describing an exhibition of John Martin's paintings at Tate Britain. Martin imagined plesiosaurs attacking an ichthyosaur as if they were engaged in fierce naval combat. But, 'if Martin's vision of prehistory is a nightmare, Kuwasseg's is a subtle and mysterious dream. Water appears in every painting, not as a seething arena for reptilian combat, but in flowing rivers, mangrove deltas, jungle waterfalls, and luminous green lagoons.' It is easy enough to find examples of Joseph Kuwasseg's 'real' landscape painting online, like the one I have included below, a view of the Leopoldsteinersee, a mountain lake in Styria. Zoë Lescaze writes that in his more conventional landscape art,

'Kuwasseg frequently includes illuminated corridors - rivers, paths, or gaps in the trees - framed by darker houses, rocks, or foliage. He incorporates these same visual tunnels in his prehistoric vistas, leading the viewers into carboniferous swamps as though they were inviting stretches of the Austrian countryside.'

Josef Kuwasseg, Leopoldsteinersee, no date

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Another landscape painter featured in Paleoart is Heinrich Harder (1858-1935), who designed the remarkable mosaics for the aquarium at Berlin Zoo which were destroyed by Allied bombing in 1943 and then painstakingly restored in 1982. Examples of his paintings of the German countryside on various auction websites give no indication of the Jugendstil influence in his mosaic designs, with their Hokusai waves and Hodler skies. The painting of sea lilies below is from a set of collectible cards, 'Animals of the Prehistoric World' (it is atypical as most show examples of megafauna wandering through ancient landscapes). Several paleoartists have worked on such cards - Harder's were made for a chocolate manufacturer. When I was growing up we used to get PG Tips tea for the cards, so one of the sources of my own knowledge on dinosaurs was their series Prehistoric Animals (1972).

Heinrich Harder, Sea Lilies, c. 1920

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Recalling now my childhood fascination with dinosaurs, I would say it was stimulated by a range of sources, from films like The Land That Time Forgot to trips to see the skeletons at the Natural History Museum and Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins' wonderful old sculptures in Crystal Palace Park (see below). When it came to paleoart though, my main inspiration was Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Reptiles (1960), illustrated by Rudolph Zallinger, an artist best known for The Age of Reptiles, a fresco for the Peabody Museum's Great Hall. There are scanned images from this book at the blog Love in the Time of Chasmosaurs (I try not to include in copyright stuff here). By the 1960s Zallinger was working on a new fresco for the Peabody, completed the year I was born, called The Age of the Mammals. 'In this sixty-foot mural,' Zoë Lescaze writes, 'the pumpkin-orange earth crackles against a brilliant blue sky. Trees run the autumnal gamut with red, green and golden foliage. The animals, pounce, stalk, scavenge, forage, and flee.'

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, Iguanadons at Crystal Palace, 1854

My own photograph from a visit in 2008

_-_Claude_Monet.jpg)