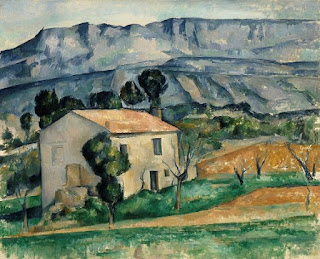

Paul Cézanne, Montagne Sainte-Victoire, c. 1890

This is a photo I took on my phone of a painting in the Tate's superb Cézanne exhibition. I won't attempt to discuss this exhibition (you can read Laura Cumming); instead I will talk about T. J. Clark's book about the artist, If These Apples Should Fall: Cézanne and the Present which I recently read. I thought I might try to distil here some of what he says about the landscape paintings, although as ArtForum's reviewer Joseph Henry points out in his review, the book 'confirms that Clark should rarely be read for his “takeaways” or “arguments.” ... What drives If Apples Should Fall is less the task of scholarly exposition than the swelling momentum of interpretation itself.' Condensing down the flow of his prose, written in 'a tone both chatty and always-already erudite', risks leaving nothing but the most familiar observation about landscape painting - that it is both an image of the world and a performance of marks on canvas. Nevertheless I'll briefly summarise some of the paragraphs from the book's concluding chapter, which mainly discusses a painting in Indianapolis, House near Gardanne.

Paul Cézanne, House near Gardanne, c. 1886-90

Clark begins by noting that the painting is not large but its landscape has 'a formidable implied scale ... The ordinariness of the house and surroundings is accompanied by a kind of distance.' In Cézanne at his strongest 'nearness and apartness' coexist.

He then starts looking closely at some of the oddities in the painting - the kind of thing we always find in Cézanne. But none of this 'ends up robbing us of 'world' and putting 'painting' in its place'.

Next he goes back into art history to contrast a Ruysdael landscape, where the viewer is invited to follow a path into the scene, with a more depthless image by Rembrandt. Cézanne's painting resembles the latter. His house fits into the landscape 'like a piece in a jigsaw, not a thing on the earth'.

Clark then returns again to a close examination of the marks making up the house, which stands out as an intervention in nature but at the same time seems porous at its edges, opening into its surroundings. That house is itself like a painting, both closed and open to the world.

Finally he shifts to a painting of Montagne Sainte-Victoire and finds in it a counter-allegory to House near Gardanne. 'The mountain is the picture, not the four-square house. And the picture, it follows, is not a closed thing', it is 'the world we are in.'