I once wrote for myself a guide to the trees and plants in Virgil's

Eclogues, drawing on the

Clarendon Press commentary by Wendell Clausen. I won't bore you with the whole thing, but will give here a brief summary to indicate how these details help create a landscape for the ten pastoral poems. Virgil's Arcadia is more artificial than the Sicily in which Theocritus set his

Idylls, but I think this makes it all the more rewarding to try to picture the details of his settings. In the course of the poems Virgil refers to both Greek and Italian places; it could be said that the

Eclogues are partly set in the North Italian countryside near Mantua, where the poet grew up, and partly, overlaid on this, in an ideal, pastoral Greece of the mind.

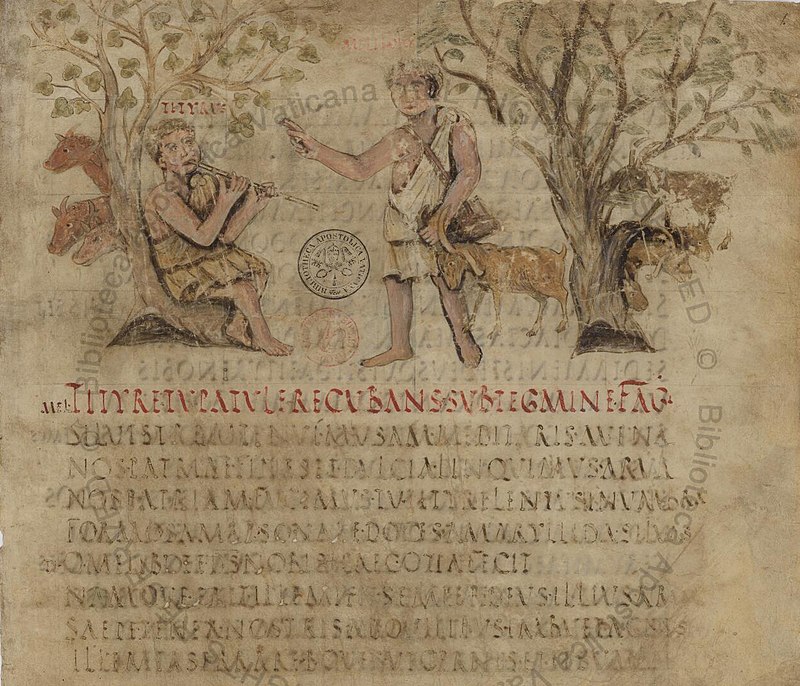

Tityrus and Meliboeus in the 5th century Vergilius Romanus

Eclogue One

The first

Eclogue begins under the cool shade of a

beech tree. Meliboeus, exiled from his farm after the land confiscations that followed the Battle of Philippi, encounters Tityrus, playing his reed pipe and teaching the woods to repeat his song 'Fair Amaryllis'. I have described this scene before,

in a post that goes on to talk about the reappearance of Tityrus in Paul Valéry’s ‘Dialogue of the Tree’ (1943). Virgil's beech woods would not have been dense, since the hills would need to have allowed grazing to take place. Meliboeus has been driving goats through the

hazel thickets and cannot let them remain to graze on the bitter

willow and

clover. He pictures Tityrus, recently freed, happy on his farm, with

bees in the willow boundary hedge and

wood pigeons and

turtle doves in the tops of the

elms. Tityrus takes pity on Meliboeus and invites him to stay the night for a meal of apple, cheese and chestnuts. The poem ends with the sun setting and the mountains casting lengthening shadows.

Eclogue Two

It is the heat of the day and the sun is driving cattle into the shade and lizards into

thorn thickets. The shepherd Corydon seeks the shade of a

beech plantation to contemplate his thwarted passion for the handsome boy Alexis. The harvesters enjoy a refreshing pottage but Corydon trails after Alexis in the heat, his hoarse voice accompanied by the

cicadas. He imagines a life together with Alexis, herding kids with switches of green

mallow. He offers him gifts: a reed pipe made of

hemlock stalks, two

roe deer, a garland created by the nymphs, a simpler offering of his own: quinces, chestnuts, plums and branches of

laurel and

myrtle. The sun goes down and Corydon thinks of his own half-pruned

vines. He decides that if Alexis rejects him, he can always find another love.

Eclogue Three

The setting for this singing match is an old

beech plantation. The judge, Palaeomon, remarks on the beauty of the wider landscape:

crops growing,

orchards full of fruit and

woodlands in leaf. The two shepherds sing of various imaginary loves. In the course of their songs, Menalcus likens his feelings for Amyntus to the way crops love the rain, goats love the

arbitus tree and breeding herds love the

willow; Damoetus describes a love-sick bull who is pining away even though he is surrounded by

vetch to eat. The contest is declared a draw and Palaeoman asks them to stop their songs, because the meadows have had their fill.

Eclogue Four

This fourth poem is not set in a landscape, its subject is politics - probably the Pact of Brundisium between Anthony and Octavian. Virgil excuses himself for leaving his pastoral theme, saying that not everyone likes the 'tamarisk' and that he will now sing a 'forest'. He evokes a Golden Age that will come with the birth of a child (possibly the future child of Antony and Octavia), when grapes will hang from thorn trees and honey will be secreted by the oak trees. Soil will need no harrowing, vines will need no pruning and - a detail that sounds rather less appealing - sheep will grow their wool in various bright colours.

Eclogue Five

Menalcus, the older of the singing shepherds in

Eclogue Three, meets Mopsus and suggests that they sit down in a grove of

hazel and

elm. But Mopsus has an alternative to sitting 'under the trees, where the light air stirs the shadows,' and proposes a cave, its entrance hanging with wild

vines. He wants to share a song that he had inscribed onto a

beech trunk (it has been pointed out that the song is rather long to have been written out in full on a tree...) He sings of the death of Daphnis, mourned by Nature so that where once there were fields of barley there now grew only

darnel and

wild oats, whilst violets and narcissi were succeded by

thistle and

thorn. Menalcus then sings his own elegy for Daphnis, saying that he will be praised as long as boars love the heights, fish love streams,

cicadas drink

dew and

bees suck

thyme.

Eclogue Six

In this poem the god Silenus sings to two shepherd boys so beautifully that the

oak trees bow their heads.

Among the myths he recounts is that of

Pasiphaë, wandering in search of the bull who rests under the ilex among soft hyacinths. The bull is described as pale, pallentis, a word that may represent the greenish yellow of summer grass. Silenus tells of Phaeton's sisters, transformed into tall alders after lamenting his death on the banks of the Eridanus. He sings all the songs that Apollo once composed and made the laurels along the river Eurotus learn. It was at Eurotus that Apollo mourned the loss of Hyacinthus. Finally evening comes and the young shepherds leave for home to count their sheep.

Eclogue Seven

The narrator is Meliboeus, from Eclogue One, who remembers being approached one day by Daphnis when he was busy protecting his myrtles from frost damage. Daphnis persuaded him to go down to the river, fringed with reeds and the sacred oak, a-drone with bees. There they witnessed a singing contest between Corydon and Thyrsis. Corydon longed for a nymph sweeter than thyme and fairer than pale ivy. He sang of the beautiful pastoral landscape: springs, soft grass, arbitus trees, vines, chestnuts and juniper bushes. He concluded by listing plants associated with the gods and heroes but saying that above these is the hazel, loved by Phyllis; Thyrsis in turn said that if only his lover Lycidas were with him more often, the ash and pine would mean nothing to him.

Eclogue Eight

This is another singing match in which the shepherd Damon laments his lost love while leaning against the trunk of an olive tree (or possibly on an olive-wood staff, like the one owned by Polyphemus in the Odyssey). He sings of a world gone awry, of alders that bear sweet narcissus and tamarisks that shed tears of amber.

Eclogue Nine

The landscape here is that of the first Eclogue, and the conversation is between Lycidas and Moeris, a dispossessed landowner who is suffering the indignity of looking after the new owner's goats. Lycidas thought that the land, which stretches down to a river where beeches grow, had been saved by the poetry of Moeris's friend. But poetry wasn't sufficient to spare this countryside; the beeches by the river have their tops broken off. The two men recall various poems, including one addressed to Galatea, which I have referred to here before. Seamus Heaney translated this and in his version the grotto of Cyclops is an undermined riverbank with swaying poplars and vines in thickets 'meshing shade with light.' Lycidas wants to hear more but Moeris is in no mood to continue.

Eclogue Ten

In this last poem Virgil himself appears in Arcadia, surrounded by his goats. He sings of his friend Gallus, who was lying love sick under a crag, while the laurels and tamarisks wept for him, when Pan, stained with the juice of elderberries, arrived with Sylvanus, wearing a coronet of fennel and Madonna lilies. Pan told Gallus not to weep over his love, but Gallus, inconsolable, vowed to live alone in the forest or by wandering in the mountains. Virgil says that he hopes this song will not displease Gallus, for whom he expresses a love that is growing hourly, like alders shooting up in the spring. He notices a chill in the air, under the shade of a juniper tree, so he gathers together his goats and heads for home.