To Kings Place last night for Yugen – the mysterious elegance of classical Noh, part of the Noh Reimagined weekend. It featured Yukihiro Isso on nohkan flute along with five other artists designated by the Japanese government as Important Intangible Cultural Assets: two actors from the Kanze school of Noh and three drummers. Yukihiro has combined his career in classical Noh with improvisation - as you can hear in the recent Cafe Oto performance embedded above - and has worked with people like Cecil Taylor, John Zorn and Peter Brötzmann. He represents the 15th generation of a family of Noh musicians and his collection of flutes includes heirlooms that are five hundred years old. The concert yesterday ended with music and dance from the play Tōru by Zeami (c. 1363 – c. 1443), whose account of his exile on the island of Sado was the subject of a post here last month. Here is the story of the play, based partly on the synopsis available on the Noh Plays Database.

On an autumn evening a monk visiting Kyoto comes to a mansion, where he meets an old man who is carrying buckets of brine on a pole, even though this place is far from the sea. The curious monk is told that this mansion used to belong to Minamoto no Tōru. Long ago he had built here a replica of the scenery of Shiogama, a place renowned for its saltwater bay. Tōru requested that people carry brine every day from Naniwa to fill the lake. He let people bake sea salt in his garden until his death. Afterwards the mansion became deserted.

It was this this last dance that we saw, with the shite (main role actor) Masaki Umano gliding slowly round the stage, dressed in a shade of pale blue that suggested the view over a saltwater bay, while behind him the flute and drums traced the course of Tōru's remembrances. As I watched, I thought about landscape and memory: the Minister compelled in life to build a replica of a place he had loved, returning from death to try to keep alive this simulacrum and then transformed from an old salt carrier to the nobleman he had once been.The monk and the old man talk about the mountains of Kyoto and the exquisite harvest moon. The old man disappears and the monk realises that he must have been the ghost of Minister Tōru. The monk goes to sleep and in his dream the ghost of Minister Tōru returns, appearing now as he did when he lived in this mansion. Illuminated in the moonlight, he dances to elegant music whilst recalling his beautiful home with its replica of the saltwater bay. At dawn, Tōru returns to the capital of the moon.

Zeami's play (which I have referred to here before) draws on a story that has its origins in a poem by Ki no Tsurayuki, who visited this mansion shortly after the death of Minamoto no Tōru in 895. Tsurayuki's poem refers to the lonely beach and vanished smoke of Shiogama, as if he were looking at the real bay instead of its replica. Tōru's death is alluded to in the image of smoke that no longer emanates from the salt fires tended by his servants. It was said that Tōru had ocean fish and crustaceans living in his lake. The real Shiogama Bay (now a harbour for Shiogama City) was a renowned beauty spot (Matsushima Bay, as the wider area is known, with its rocky islands rising out of the sea, is one of the Three Views of Japan). Shiogama was, according to legend, the first place in Japan where salt was extracted by boiling sea water. In The Art of Japanese Gardens (1940), Loraine E. Kuck speculated that Tōru may have originally seen Shiogama on an expedition to what was then the country's northern frontiers, where Ainu tribes were still fighting the advance of the Japanese. Back in Kyoto at his villa on the banks of the Kamo, while his servants boiled salt on the edge of his lake, Tōru could 'sit and watch the ever-changing flutter of the smoke banner across the sky and romantically imagine himself far away in the picturesque north country.'

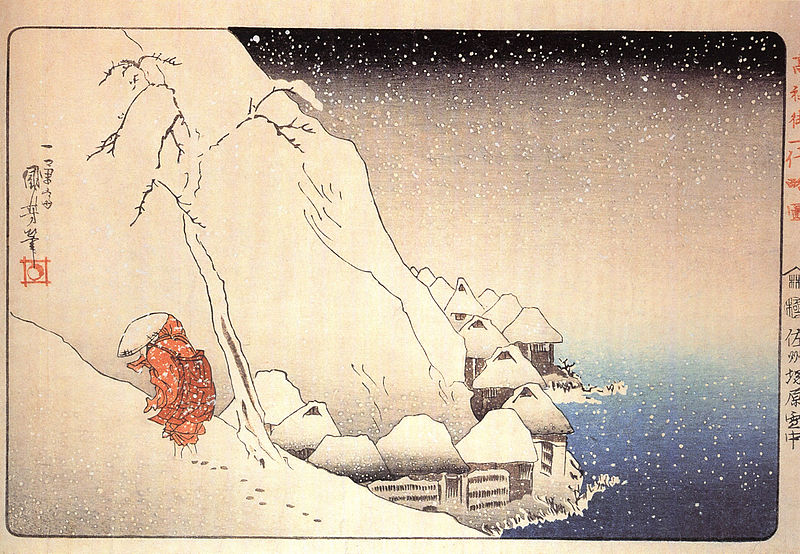

Kikuchi Yosai, Minamoto no Tōru, 19th century