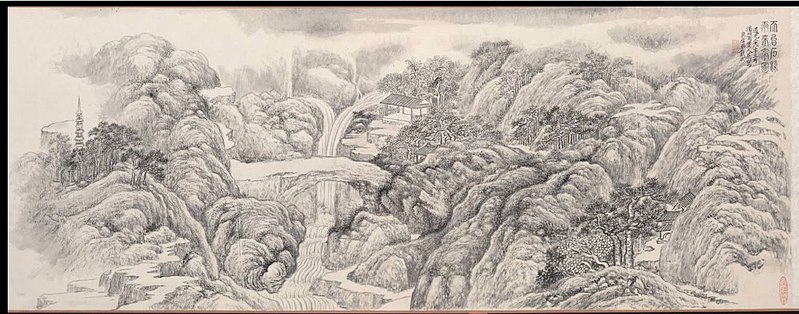

Autojektor, Basilisk, 2019

Well, the weeks drag on and I am starting to forget what hills, rivers and shorelines actually look like. I keep wondering whether it is worth the health risk to hire a car or take a train to see something other than Victorian terraces. But where would we go? The virus has drawn attention to the way we pick destinations to experience and how much effort we are prepared to make to get to them. Conversely it has shown how much interest there is in exploring the local streets - not exactly deep topography, but still a lesson in noticing previously overlooked details. I'm sure I'm not alone in having made a short film based on these exercise walks - it seemed an obvious thing to do, even if I am no Jonathan Meades (despite insisting on posing in similar shades).

Lockdown walks near our home in London

Mersea Island photographed by me in 2011

When I asked my wife where, in theory, she would most like to travel to outside London, she thought about it for a bit and then started reminiscing about Mersea Island. I was thinking about this when I started reading a place-themed edition of the Moving Image Artists Journal, since Mersea Island is actually where the editors Danial & Clara have been living under lockdown. How, I wondered, did these different filmmakers, with all the possibilities of mobility before coronavirus, choose particular landscapes to be the focus of their films? A few examples from the thirteen articles:

- Estrangement and escape: The Super 8 artist Autojektor lives in London but made Basilisk in the Black Forest. They refer to the story of Hansel and Gretel, lost in the woods, and write of being an innocent abroad themselves: 'as someone that had only been out of the country once before as a kid, it was easy to lose myself.' The landscape became a creative space to escape from our permanently connected world. 'I would purposely get myself lost – I’d let my phone run down and I’d walk into the thickest woods and heaviest fog until I started to panic. And then I would sit and write.'

- Memory and family history: 'Landscape is the lens through which I see the world, and the landscape of my lifetime is defined by loss,' writes Seán Vicary. His project, Chain Home West, involved 'active place-based research, that was often reflexive and sometimes even ritualistic or performative.' The film's locations had personal associations and centred on his desire to seek out the site of a mobile radar unit that his father had been assigned to during the war.

- Hauntology and psychogeography: For Headlands, Yvonne Salmon and James Riley headed to a hauntologically-rich location in North Cornwall: setting for a 1981 BBC Series, The Nightmare Man, and linked to a 17th century maid who is recorded as having encountered fairies (or possibly aliens). On their filming trip, 'things happened which we found difficult to explain' and they returned from Cornwall 'not the same people who started out on the journey.'

- Aesthetic choice: Peter Traherne's Atmospheric Pressure began with an attempt to make a film inspired by Gawain and the Green Knight. In looking for locations he found a farm in Sussex with flooded fields and dead pigs. 'Needless to say, the location charmed me. Maybe not the carcasses but the texture of it all.' The Gawain theme was dropped in favour of a film about 'The Farmer', although the real farmer's involvement was not straightforward: 'we could never shoot his scenes, for he must always be elsewhere.' The film crew eventually left with 'dark images of a world of weather and animals; images that were densely uncommunicative yet surfeited with sense and matter'.

- Residency: finally, some settings get chosen because they are readily to hand. Daniel & Clara write about filming with old VHS cameras on walks near their former home in Hastings, or assembling footage taken on a daily basis in Portugal to form a composite landscape film (see below). They have also taken the opportunity to film when invited to participate in exhibitions or other projects. In another article, Amy Cutler (whose curating I have written about here before) discusses her recent filmmaking and refers to an artist residency on the Finnish fortress island of Örö last winter.