Narcisse Virgilio Díaz, Forest of Fontainebleau, 1868

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Forest of Fontainebleau has a special place in the history of western landscape art: painted repeatedly by the Barbizon School and the Impressionists who took inspiration from them. That there is still a forest to explore is down in part to Théodore Rousseau: he 'appealed to Napoleon III to halt the wholesale destruction of the forest’s trees, and in 1853 the emperor established a preserve to protect the artists’ cherished giant oaks' (see the Met's online essay on the Barbizon School). We were in Fontainebleau on that fiercely hot weekend earlier this month and I yearned to head into the forest to find some of that deep shade painted by Rousseau's friend Narcisse Virgilio Díaz. But we'd come for culture rather than nature, to visit the Château de Fontainebleau. Emerging from its opulent rooms in the full heat of the afternoon we made our way across the Grand Parterre, with its low hedges and topiary cones stretching into the distance. This flat, mathematical space, planned out by André Le Nôtre and Louis Le Vau, is as different a landscape as can be imagined from the dense wooded slopes and tenebrous clearings explored by the Barbizon painters. Strange then to find at its centre, beneath the surface of a square ornamental pool, a miniature forest, swaying gently in the cool, clear water.

Before the Barbizon School there was the School of Fontainebleau, two schools in fact, the first comprising artists brought to decorate the palace during the sixteenth century (including Benvenuto Cellini, who describes the work in his wonderfully vivid Autobiography), the second at the beginning of the seventeenth during one of the phases of renovation and redecoration that continued down to Napoleon's time. These Mannerist artists were much more interested in mythological figures and allegorical references than in anything to do with landscape, as can be seen in the print below, where a rocky scene is completely dominated by its framing figures. There are numerous references to hunting in their decorative schemes: the forest as resource for the king's pleasure. The Palace contains a Gallery of Diana and a Gallery of Stags. There is also a Jardin de Diane, with a fountain dating from the early nineteenth century dedicated to the goddess; its water comes from the mouths of stags and, as my son's were quick to point out, four "pissing dogs".

Antonio Fantuzzi, Cartouche with male and female satyrs

carrying baskets and flanking a rocky landscape, 1543

Source: Wikimedia Commons

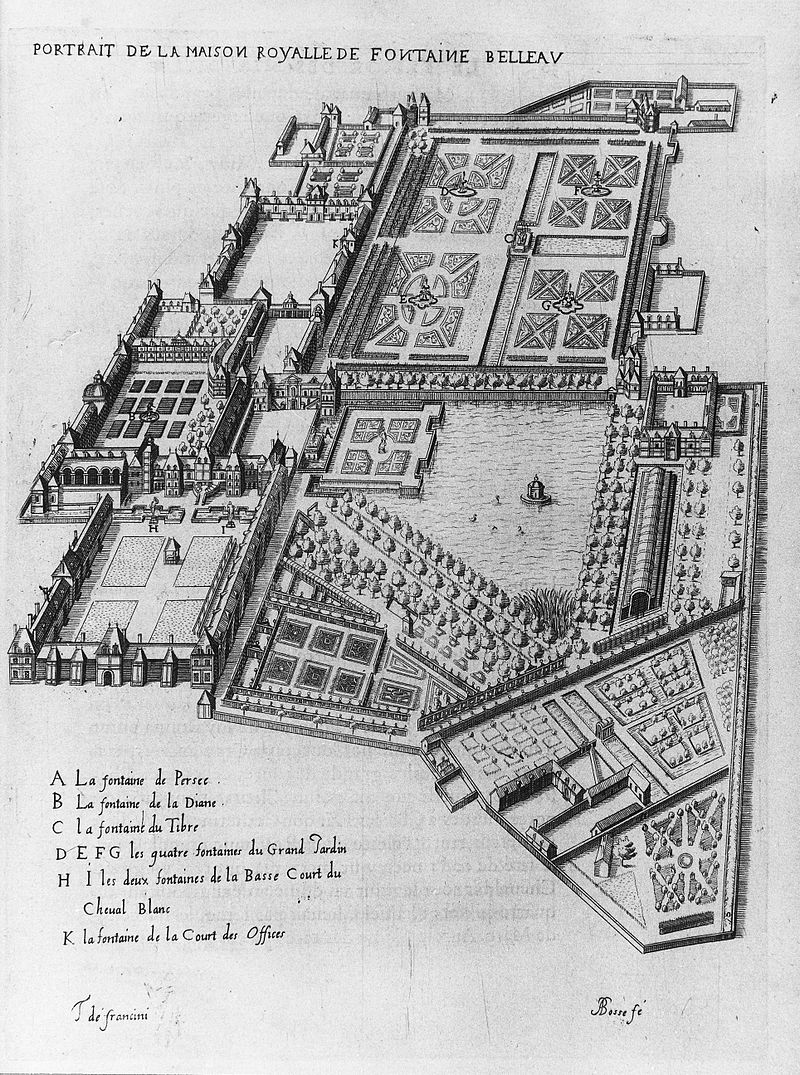

Tommaso Francini, The Château and Gardens, early 17th century

Source: Wikimedia Commons

One of the Valois Tapestries, showing a festival on the lake at Fontainebleau,

made shortly after 1580.

The Carp Lake visible in the seventeenth century plan shown above is still there (as are the carp). The photograph of it below was taken from a rowing boat that I was pressed into hiring. The lake at Fontainebleau can also be seen in one of the Valois Tapestries, made to commemorate eight of Catherine de' Medici's famous court festivals. This one took place in 1564 and was just one event in the royal progress that took her and her son, the new king, two and a half years to complete. The household accompanying them included her 'flying squadron' (L'escadron volant) of eighty seductive ladies-in-waiting, and nine dwarfs who travelled in their own miniature coaches. The great poet Pierre de Ronsard was present at Fontainebleau, where there were feasts, jousts, sirens singing, Neptune floating in his chariot and an attack on an enchanted island. I wonder how many of them thought about the real forest beyond the Château as they acted out imaginary battles in an artificial landscape. A century later the island in the lake was given a small pavilion; later it was restored by Napoleon. We were warned as we climbed into the boat not to row too close it, although I don't think our inept collective efforts at steering could have got us there anyway.

.jpg/1280px-Charles_Blomfield_-_White_terraces%2C_Rotomahana_(1903).jpg)

_p275_THE_PINK_TERRACE%2C_NEW_ZEALAND.jpg?uselang=en-gb)