Sunday, September 26, 2010

Windings of the River Tummel

Inspired by a recent visit to Scotland, I have been reading the Yale edition of Dorothy Wordsworth's Recollections of a Tour Made in Scotland. The pleasures of this text are considerably enhanced by editor Carol Kyros Walker's atmospheric black and white photographs, taken as she retraced Dorothy's route. Walker explains her decision not to use colour photography with reference to the process of writing an account of a journey. 'In calling up, and re-collecting the images of a place there must be a moment just before total illumination in the mind when what is there pauses for the final investment of the thinker. For me, that instant is in black and white.' The Recollections itself comprises two distinct sections and modes of recall: the first written in 1803 just after Dorothy's return from Scotland and full of daily detail, the second written in 1805 and prefaced with a note explaining that the style and tone had been affected both by the passage of time and the recent loss of her brother in a shipwreck.

The Recollections demonstrate an impressive willingness to endure physical discomfort in the search for Romantic scenery. Dorothy Wordsworth travelled with her brother and Samuel Taylor Coleridge in an Irish 'jaunting car' - an open-air two wheeled cart that made the landscape more accessible than a chaise, and which provoked amused or suspicious looks at various points along the way. Their poor horse had a miserable time of it, ending up frightened by even the suspicion of another awful loch crossing, and the travellers encountered dirt and inhospitality at many of the inns and homes along the way (not surprising given the prevailing poverty and resentfulness towards England and the ongoing Highland Clearances). The terrain and roads could be difficult too and Carol Kyros Walker lists the distances travelled, along with the adjective Dorothy uses for that part of the route. The resulting table reads to me like a Richard Long text piece, for example:

Killin (tolerable) 7

Kenmore (baddish) 15

Blair (bad) 23

Fascally (wretchedly bad) 18

Dunkeld (bad) 12

Ambletress (hilly - good) 10

Crieff (hilly - goodish) 11

Loch Erne Head (tolerable) 20

Callander (most excellent) 14

Dorothy Wordsworth used various means of evoking the landscape - topographical description, reference to earlier writers like Sir John Stoddard, quotation from Wordsworth's poems ('To a Highland Girl', 'Stepping Westward', 'The Solitary Reaper' etc.) She also made some sketches, like this one of the River Tummel, 'a glassy river' gliding through the level ground 'not in serpentine windings, but in direct turnings backwards and forwards.' There is no doubt that she was influenced by writers on the Picturesque (Walker refers to a study on this by John R. Nabholtz which notes, for example, that her sensitivity to the absence of trees may reflect the aesthetics of Uvedale Price). She remarks upon the landscape's 'inhabited solitudes' and sometimes sees isolated figures in pictorial terms, like the melancholy woman alone in a desolate field and an old man exhibiting 'a scriptural solemnity'. These provoke the thought that in Scotland 'a man of imagination may carve out his own pleasures'. Walking over the brow of a hill at twilight, she sees a boy wrapped in grey plaid, calling to his cattle in Gaelic. 'His appearance was in the highest degree moving to the imagination... It was a text, as William has since observed to me, containing in itself the whole history of the Highlander's life - his melancholy, his simplicity, his poverty, his superstition, and above all, that visionariness which results from a communion with the unworldliness of nature.'

Both Dorothy and William Wordsworth noticed the changes being made to the landscape - deploring the felling of trees at Neidpath Castle, for example, and complaining at Douglas Mill that 'large tracts of corn; trees in clumps, no hedgerows ... always make a country look bare and unlovely'. Carol Kyros Walker finds much of what Dorothy wrote about unaltered, with a few obvious changes (the photograph of a 'solitary reaper' shows a distant tractor). Nevertheless, the 'astounding flood', as William described the falls of Cora Linn, appears less impressive now that hydroelectirc power has been introduced to the Clyde. Dunglass Castle can still be seen on its promontory, where Dorothy, admired the view 'terminated by the rock of Dumbarton, at five or six miles distance, which stands by itself, without any hills near it, like a sea rock.' However, the accompanying footnote explains that the castle, later home to Charles Rennie Mackintosh, eventually became a stationery store. 'It is now on the grounds of an ESSO oil terminal which is kept under strict security. To visit the castle one must be escorted by an ESSO guard and agree to don a hard hat.'

Labels:

rivers,

Uvedale Price,

William Wordsworth

Location:

River Tummel

Sunday, September 12, 2010

Carmel Point

I have been kindly invited to go to Glasgow this week to take part in a conversation as part of the Values of Environmental Writing Research Network. Part of the discussion will consider Dark Mountain, 'a new cultural movement for an age of global disruption', and Uncivilisation: The Dark Mountain Manifesto, with its call for writing and art grounded in a sense of place and time, which steps outside the human bubble to reengage with the non-human world. The authors, Paul Kingsnorth and Dougald Hine, state that 'our whole way of living is already passing into history. We will face this reality honestly and learn how to live with it. We reject the faith which holds that the converging crises of our times can be reduced to a set of 'problems' in need of technological or political ‘solutions’.' This pessimistic view has met with opposition, from George Monbiot for example: 'to sit back and wait for what the Dark Mountain people believe will be civilisation's imminent collapse, without trying to change the way it operates, is to conspire in the destruction of everything greens are supposed to value.' In a critical Guardian article, Solitaire Townsend worries that 'Dark Mountain isn't a prophesy: it's the outcome of inaction' and likens them to the diners at The Restaurant at the End of the Universe.

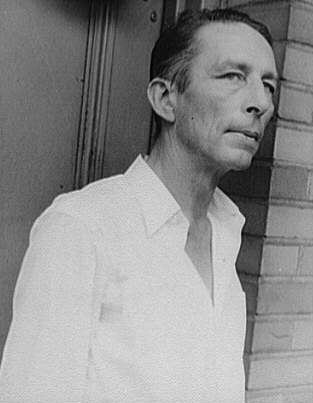

Robinson Jeffers' Hawk Tower, Tor House, Carmel

These criticisms echo those made at various times of Robinson Jeffers, the poet cited by Dark Mountain as a key inspiration, who advocated a philosophy of 'inhumanism' and opposed US involvement in the war - 'the fever-dreams of decaying Europe'. Addressing the tower he built at Carmel, he wrote "look, you gray stones / Civilization is sick: stand awhile and be quiet and drink, the sea-wind, you will survive / Civilization." This poem, 'Pearl Harbor', and others in his 1948 book The Double Axe provoked a disclaimer from his publishers and many hostile reviews. The Dark Mountain Manifesto acknowledges that Jeffers' reputation has suffered: 'today his work is left out of anthologies, his name is barely known and his politics are regarded with suspicion. Read Jeffers’ later work and you will see why. His crime was to deliberately puncture humanity’s sense of self-importance. His punishment was to be sent into a lonely literary exile from which, forty years after his death, he has still not been allowed to return.'

Robinson Jeffers may not be as well regarded now as he was eighty years ago, but his poems are still read and 'Carmel Point' appears in two recent anthologies of environmental poetry, Earth Shattering and Wild Reckoning. His inhumanism in this poem is not too extreme: 'we must unhumanize our views a little', he says. 'This beautiful place defaced with a crop of suburban houses— / How beautiful when we first beheld it, / Unbroken field of poppy and lupin walled with clean cliffs.' Jeffers is reassured that the landscape 'knows the people are a tide / That swells and in time will ebb, and all / Their works dissolve.' This theme of ecofatalism recurs in many Jeffers poems. In his book Ecocriticism Greg Garrard draws a connection between Jeffers (along with Lawrence and Nietzsche) and the more extreme biocentric beliefs espoused by some radical environmentalists. He also quotes Gary Snyder, who, though influenced by Jeffers, complains that his 'tall cold view' does not seem to have room for 'the inhuman beauty / of parsnips or diapers, the deathless / nobility at the core of all ordinary things.'

I think it is possible to agree with Snyder without wishing to read too many poems about diapers (having had six years of them I am thoroughly acquainted with their deathless nobility). Jeffers had two sons, and wrote 'I shall die, and my boys / Will live and die, our world will go on through its rapid agonies of change and discovery; this age will die.' This poem also illustrates the way Jeffers could write about the Californian landscape: 'we stayed the night in the pathless gorge of Ventana Creek, up the east fork. / The rock walls and the mountain ridges hung forest on forest above our heads, maple and redwood, / Laurel, oak, madrone, up to the high and slender Santa Lucian firs that stare up the cataracts / Of slide-rock to the star-color precipices...' For more on Jefferson and landscape you can browse the archives of the Jeffers Studies site: see for example 'Robinson Jeffers and the California Sublime', 'Robinson Jeffers' California Landscape and the Rhetoric of Displacement', 'The Essential landscape: Jeffers among the photographers' and three articles on Jeffers, geology and rocks. Of particular relevance to this post is Peter Quigley's article 'Carrying the Weight: Jeffers’s Role in Preparing the Way for Ecocriticism'.

I think it is possible to agree with Snyder without wishing to read too many poems about diapers (having had six years of them I am thoroughly acquainted with their deathless nobility). Jeffers had two sons, and wrote 'I shall die, and my boys / Will live and die, our world will go on through its rapid agonies of change and discovery; this age will die.' This poem also illustrates the way Jeffers could write about the Californian landscape: 'we stayed the night in the pathless gorge of Ventana Creek, up the east fork. / The rock walls and the mountain ridges hung forest on forest above our heads, maple and redwood, / Laurel, oak, madrone, up to the high and slender Santa Lucian firs that stare up the cataracts / Of slide-rock to the star-color precipices...' For more on Jefferson and landscape you can browse the archives of the Jeffers Studies site: see for example 'Robinson Jeffers and the California Sublime', 'Robinson Jeffers' California Landscape and the Rhetoric of Displacement', 'The Essential landscape: Jeffers among the photographers' and three articles on Jeffers, geology and rocks. Of particular relevance to this post is Peter Quigley's article 'Carrying the Weight: Jeffers’s Role in Preparing the Way for Ecocriticism'.

Friday, September 10, 2010

The Woods of Raasay

Alec Finlay and Ken Cockburn have now reached Raasay on the Road North. Their most recent post pays tribute to Sorley MacLean (Somhairle MacGill-Eain), the great poet of Raasay, and his poem 'Hallaig'. They include a map, a Borgesian signpost and three hokku labels pinned to trees - 'she is birch', 'she is rowan', 'she is hazel'. These refer to the lines 'tha i 'na beithe, 'na calltuinn, / 'na caorunn dhìreach sheang ùir'. Maclean translated these lines into English as 'she is a birch, a hazel, / a straight slender young rowan' and Seamus Heaney's version has 'A flickering birch, a hazel, / A trim, straight sapling rowan'.

In a 2002 lecture Heaney wrote about how impressed he had been by 'Hallaig', a poem that arose 'out of MacLean's sense of belonging to a culture that is doomed but that he will never deny. It's as local as anything in Thomas Hardy and as lambent as Rilke's Sonnets to Orpheus'. 'Hallaig' is a landscape emptied by the Highland clearances. The poem is 'set at twilight, in the Celtic twilight, in effect, at that time of day when the land of the living and the land of the dead become pervious to each other, when the deserted present becomes populous with past lives, when the modern conifers make way for the native birch and rowan, and when the birch and rowan in their turn metamorphose into a procession of girls walking together out of the 19th-century hills. The poem tells us that in Hallaig there is something to protect, and goes on to show that it is indeed being protected, which is the reason for the uncanny joy a reader feels at the end.'

'Hallaig' is this month's featured poem on the Sorley MacLean Trust website. They quote John MacInnes, who says that in 'Hallaig' 'both the Gaelic sense of landscape, idealised in terms of society, and the Romantic sense of communion with Nature, merge in a single vision, a unified sensibility.’ The same could be said of another Sorley MacLean poem, 'Coilltean Ratharsair' ('The Woods of Raasay'), which begins like a Gaelic version of The Prelude (as Terry Gifford says in Green Voices: Understanding Contemporary Nature Poetry). In its early verses the poem recalls the woods in motion, in blossom, in sunlight and shade, many-coloured, many-winded, serene and humming with song. But the imagery becomes darker ('O the wood! / How much there is in her dark depths!') and there is a growing recognition that idealised woods are as unattainable as perfect love. 'What is the meaning of worshipping Nature / because the wood is part of it?' In the end, wood itself is simple - 'the way of sap is known' - but 'there is no knowledge of the course of the crooked veering of the heart' or 'of the final end of each pursuit.'

In a 2002 lecture Heaney wrote about how impressed he had been by 'Hallaig', a poem that arose 'out of MacLean's sense of belonging to a culture that is doomed but that he will never deny. It's as local as anything in Thomas Hardy and as lambent as Rilke's Sonnets to Orpheus'. 'Hallaig' is a landscape emptied by the Highland clearances. The poem is 'set at twilight, in the Celtic twilight, in effect, at that time of day when the land of the living and the land of the dead become pervious to each other, when the deserted present becomes populous with past lives, when the modern conifers make way for the native birch and rowan, and when the birch and rowan in their turn metamorphose into a procession of girls walking together out of the 19th-century hills. The poem tells us that in Hallaig there is something to protect, and goes on to show that it is indeed being protected, which is the reason for the uncanny joy a reader feels at the end.'

'Hallaig' is this month's featured poem on the Sorley MacLean Trust website. They quote John MacInnes, who says that in 'Hallaig' 'both the Gaelic sense of landscape, idealised in terms of society, and the Romantic sense of communion with Nature, merge in a single vision, a unified sensibility.’ The same could be said of another Sorley MacLean poem, 'Coilltean Ratharsair' ('The Woods of Raasay'), which begins like a Gaelic version of The Prelude (as Terry Gifford says in Green Voices: Understanding Contemporary Nature Poetry). In its early verses the poem recalls the woods in motion, in blossom, in sunlight and shade, many-coloured, many-winded, serene and humming with song. But the imagery becomes darker ('O the wood! / How much there is in her dark depths!') and there is a growing recognition that idealised woods are as unattainable as perfect love. 'What is the meaning of worshipping Nature / because the wood is part of it?' In the end, wood itself is simple - 'the way of sap is known' - but 'there is no knowledge of the course of the crooked veering of the heart' or 'of the final end of each pursuit.'

Labels:

Alec Finlay,

huts,

Seamus Heaney,

trees

Location:

Raasay

Saturday, September 04, 2010

A lake of fire awaiting the final sunset

Sight and Sound's October 'Film of the Month' is Sarah Turner's Perestroika, 'a journey into both the snowy wastes of Siberia and the fractured mind of its grieving narrator'. Chris Darke's review makes a connection with the recent resurgence in British nature writing, wondering if similar trends in film will be equally germane to our environmental fears: 'The 'landscape film' is a hardy sub-genre of British experimental cinema, from Chris Welsby's elemental 1970s nature studies, via Derek Jarman's The Garden (1990) - a record of his own little acre in the shadow of Dungeness nuclear power station - to the contemporary work of Peter Todd and Emily Richardson. In her remarkable film Perestroika, the British artist-film-maker Sarah Turner reinvents the genre for the present day: the 'landscape film' under the sign of extinction.'

I have not yet seen the film but have been reading about it at Catherine Grant's filmanalytical and the links provided there. The director sees her film explicitly as 'an environmental allegory. Hot and cold represent the relationship between inside and outside. Inside the train is boiling because of the heaters and thick glass but you’re passing through a freezing landscape. In the developed world we sit in our overheated units while outside our planet heats up. The change is evident in the landscape itself. There are great swathes without snow and they’re harvesting wheat, in December, in Siberia.' What Chris Darke describes as the film's 'extreme psychogeography' culminates in the narrator's vision of Baikal, the deepest lake in the world 'and the zero-point of Siberia's status as a weathervane of global warning, landscape and mind', as 'a lake of fire awaiting the final sunset'.

Monday, August 30, 2010

The King Lake and the Watzmann

A couple of years ago the Pushkin Press published a new translation of Der Hagestolz (1850) by Adalbert Stifter (1805-68). Their edition comes with a beautiful cover, The King Lake and the Watzmann (1837), painted by Stifter himself when his main energies were focused on landscape painting, prior to the publication of his first story Der Condor in 1840. The image is perfect because the story's hero Viktor is forced to stay on an island in a lake surrounded by mountains. There his youthful energy and generous spirit convince the miserly uncle who has summoned him there to provide for Viktor and save him from the dull and restricting administrative career he was intending to pursue.

The book has many vivid passages of landscape description, like the moment Viktor wakes and looks out from the island, seeing the distant mountains shining in the sun: 'everywhere broad shadows were cast; and the whole spectacle appeared again in the lake, which, swept clean of every wisp of mist, lay there like the most delicate of mirrors.' Viktor at the window (that archetypal Romantic moment) is 'awestruck. The sharpest of contrasts was created by all this encircling profusion of light and colours alongside the surrounding deathlike silence in which theses gigantic mountains stood' (trans. David Bryer). Like other artist writers (Mervyn Peake for example), Stifter's descriptions are always sensitive to the distribution and intensity of light.

Pushkin also publish Stifter's Bergkristall (Rock Crystal) in a 1945 translation by Elizabeth Mayer and Marianne Moore, a writer one can well imagine being sympathetic to Stifter's gentle, poetic stories. This is another story that takes place in the shifting light of the mountains, where darkness falls on a winter journey and two children are lost in the snow. As I have promised to read this story to Mrs Plinius one Christmas Eve I shall say no more about it here, but if you're interested I can recommend a good article about Rock Crystal by Adam Kirsch. He quotes Hannah Arendt's review of the 1945 edition, where she described Stifter as "the greatest landscape painter in literature ... someone who possesses the magic wand to transform all visible things into words."

The book has many vivid passages of landscape description, like the moment Viktor wakes and looks out from the island, seeing the distant mountains shining in the sun: 'everywhere broad shadows were cast; and the whole spectacle appeared again in the lake, which, swept clean of every wisp of mist, lay there like the most delicate of mirrors.' Viktor at the window (that archetypal Romantic moment) is 'awestruck. The sharpest of contrasts was created by all this encircling profusion of light and colours alongside the surrounding deathlike silence in which theses gigantic mountains stood' (trans. David Bryer). Like other artist writers (Mervyn Peake for example), Stifter's descriptions are always sensitive to the distribution and intensity of light.

Pushkin also publish Stifter's Bergkristall (Rock Crystal) in a 1945 translation by Elizabeth Mayer and Marianne Moore, a writer one can well imagine being sympathetic to Stifter's gentle, poetic stories. This is another story that takes place in the shifting light of the mountains, where darkness falls on a winter journey and two children are lost in the snow. As I have promised to read this story to Mrs Plinius one Christmas Eve I shall say no more about it here, but if you're interested I can recommend a good article about Rock Crystal by Adam Kirsch. He quotes Hannah Arendt's review of the 1945 edition, where she described Stifter as "the greatest landscape painter in literature ... someone who possesses the magic wand to transform all visible things into words."

Labels:

ice,

lakes,

light,

mountains,

window views

Location:

Watzmann

Saturday, August 28, 2010

The Green Pasture

'I know a painting so evanescent that it is seldom viewed at all, except by some wandering deer. It is a river who wields the brush, and it is the same river who, before I can bring my friends to view his work, erases it forever from human view. After that it exists only in my mind's eye.' I'm always interested in examples of the landscape creating its own art, and in 'The Green Pasture' section of his environental classic A Sand County Almanac (1949), Aldo Leopold writes of the way the river builds up a painting, first with silt and then with plants which in turn attract birds and animals.

'To view the painting, give the river three more weeks of solitude, and then visit the bar on some bright morning just after the sun has melted the day-break fog. The artist has now laid his colors, and sprayed them with dew. The Eleocharis sod, greener than ever, is now spangled with blue mimulus, pink dragon-head, and the milk-white blooms of Sagittaria. Here and there a cardinal flower thrusts a red spear skyward. At the head of the bar, purple ironweeds and pale pink joe-pyes stand tall against the wall of willows. And if you have come quietly and humbly, as you should to any spot that can be beautiful only once, you may surprise a fox-red deer, standing knee-high in the garden of his delight.'

'To view the painting, give the river three more weeks of solitude, and then visit the bar on some bright morning just after the sun has melted the day-break fog. The artist has now laid his colors, and sprayed them with dew. The Eleocharis sod, greener than ever, is now spangled with blue mimulus, pink dragon-head, and the milk-white blooms of Sagittaria. Here and there a cardinal flower thrusts a red spear skyward. At the head of the bar, purple ironweeds and pale pink joe-pyes stand tall against the wall of willows. And if you have come quietly and humbly, as you should to any spot that can be beautiful only once, you may surprise a fox-red deer, standing knee-high in the garden of his delight.'

Eleocharis

Photo: Wikimedia Commons (James Lindsey at Ecology of Commanster)

There are several instances in the book where nature is described as a superior, more fundamental kind of culture - the essay that follows 'The Green Pasture', for example, is called 'The Choral Copse' and describes 'the misty autumn daybreaks ... What one remembers is the invisible hermit thrush pouring silver chords from impenetrable shadows; the soaring crane trumpeting from behind a cloud; the prairie chicken booming from the mists of nowhere; the quail’s Ave Maria in the hush of dawn.' This kind of artistic epiphany in the landscape is a nice way of promoting the land ethic to city folk like me who admire the naturalist's endless curiosity and patient observation of wildlife but, to be honest, would rather not read too much of the detail.

Monday, August 23, 2010

Sometimes Doing Something Leads to Nothing

Francis Alÿs, The Loop, Tijuana - San Diego 1997

Postcard given free at the exhibition Francis Alÿs: A Story of Deception

In my previous post on Francis Alÿs I described When Faith Moves Mountains, a communal effort that challenged earlier land art. "When Richard Long made his walks in the Peruvian desert, he was pursuing a contemplative practice that distanced him from the immediate social context. When Robert Smithson built the Spiral Jetty on the Salt Lake in Utah, he was turning civil engineering into sculpture and vice versa. Here, we have attempted to create a kind of Land art for the land-less, and, with the help of hundreds of people and shovels, we created a social allegory." In this exhibition there were other works that provided interesting contrasts with land artists, like Paradox of Praxis 1 (Sometimes Doing Something Leads to Nothing) (1997) where, three years before Andy Goldsworthy left snowballs melting around London, Alÿs was pushing a block of ice around the centre of Mexico City until it disappeared.

This kind of walking project, reminiscent of Richard Long but with a strong social or political edge, has been a persistent element of Alÿs's practice. In The Green Line he trod the 1948-67 border between Israel and Jordan dripping green paint as he went. In The Collectors (1990-92) he walked round Mexico City with magnetised 'dogs' collecting metal detritus. And in my favourite, Patriotic Tales (1997), he 'led a circle of sheep around the flagpole in the Zócalo, the ceremonial square and the site of political rallies. The action is based on an event in 1968 when civil servants were paraded in the city to show support for the government, but bleated like sheep to protest their subservience.'

Location:

Mexico City

Saturday, August 14, 2010

On the Island of Saint-Pierre

Near the start of this section of Civilisation (1969) we see Kenneth Clark sitting in a rowing boat discussing the 'revolution in human feeling' that occurred when Jean-Jacques Rousseau spent two months on the Island of Saint-Pierre in 1765. 'In listening to the flux and reflux of the waves, he tells us, he became completely at one with nature, lost all consciousness of an independent self, all painful memories of the past or anxieties about the future, everything except the sense of being.' It is one of those points in the series where the beauty of the colour photography and ambient sounds convey as much as Clark's words.

The writing referred to here is the fifth of Rousseau's ten Reveries of the Solitary Walker, composed during the last two years of his life (1776-78). There he says that 'everything is in constant flux' and 'our earthly joys are almost without exception the creatures of a moment.' But happiness can be found as long as we can experience nothing but 'the simple feeling of existence, a feeling that fills our soul entirely ... Such is the state I often experienced on the Island of Saint-Pierre in my solitary reveries, whether I lay in a boat and drifted where the water carried me, or sat by the shores of the stormy lake, or elsewhere, on the banks of a lovely river or a stream murmuring over the stones' (trans. Peter France). When writing The Reveries of the Solitary Walker Rousseau was living in Paris, but able to escape the city in order to breath freely under the trees. The quiet happiness he was able to experience was only possible because he had learned to rid himself of 'self-love' (amour-propre) and leave behind the bustle of the world.

This fifth walk gives an account of Rousseau's happy life on the island walking, botanising, boating and losing himself in reverie, and within the book as a whole it comes as refreshing contrast to the other walks, with their sad and bitter complaints against the enemies he saw all around him. In this it is very like the all-too-brief description Rousseau gives of the island in Confessions. This comes in Book 12, a detailed account of his troubles which starts: 'This is where the works of darkness begin, in which for eight years I have found myself entombed without it being possible for me, however I have gone about it, to penetrate their terrifying obscurity'. Rousseau describes the landscape as a refuge from his persecutors. 'Often, abandoning my boat to the mercy of wind and water, I would give myself up to a reverie without object, and which, for being foolish, was none the less sweet. At times, filled with emotion, I would cry aloud, "O nature! O my mother! Here at least I am under your guardianship alone; no cunning or treacherous man can come between us here." In this way I would drift up to half a league from the shore; I should have liked this lake to be the ocean' (trans. Angela Scholar).

Friday, August 13, 2010

The Magnetic City

Ten years ago I went to the Hayward Gallery's Sonic Boom exhibition where one of the more memorable works, Christina Kubisch's Oasis 2000: Music for a Concrete Jungle, required us to put on headphones that replaced the noise of the city on the gallery's bleak concrete terrace with a soundworld recorded in a distant rain forest. In more recent years the city itself has been the subject of her investigations and in her 'electrical walks' participants wear special headphones that pick up the waves emanating from 'light systems, transformers, anti-theft security devices, surveillance cameras, cell phones, computers, elevators, streetcar cables, antennae, navigation systes, automated teller machines, neon advertising, electric devices, etc.' As she says in the liner notes to the album The Magnetic City (2008), recorded in Poitiers, "often what you can see normally and what you hear electromagnetically, is quite different: quiet streets burst out with strong electrical hums, the lively market place is quiet instead, the train station is a dense net of regular beats and clicks, the parking Carnot is the place where antennas fill the air with internet signals, the ATM machines of the banks hum musical chords and the security gates in the shopping streets surprise by their volume and intensity of continuous signals."

In an interview in Cabinet Magazine she describes the sonic characteristics of different cities. "In Bremen, there’s a tram system that you hear all over the city, even when you’re not near it. It’s a kind of basic drone that’s very present. And in Madrid, a really persistent sound is that of the mobile phones that people carry around. You don’t hear people talking, of course. But you hear when they dial—that moment when the information is being transported. It’s a sort of short chirp: dip, da-rip, da-rip, da-rip, something like that. You hear that every moment, sometimes in duos or trios, because, in Madrid, everyone lives with their phones. In Taiwan the sounds are very aesthetic. Maybe they have a new technology that’s already very sophisticated. In Paris you have some very heavy sounds, like in the train stations, where there is so much interrupted current. Train stations in general are very full, heavy, and dusty with sound." You can hear sound samples at the Cabinet Magazine website or by clicking on the link to Boomkat below:

Wednesday, August 11, 2010

The sand and the stars

Last year I finally finished converting all my CDs to MP3s and while going through the crates came upon some Flying Saucer Attack albums, like Chorus (above), which I hadn't really listened to in at least a decade. I thought about a post then on FSA's use of landscape imagery but didn't think I had much to say about it. However, I was interested to read this week in the latest edition of Wire about the links between their strain of pastoral post-rock and the hauntology of the Ghost Box label, which I discussed here a few years ago. In his article Joseph Stannard also makes connections with Richard Youngs, Fredrik Ness Sevendal and the groups associated with the Jewelled Antler Collective (mentioned in passing in a recent post about Richard Skelton).

Flying Saucer Attack's music had by the mid 90s, according to Stannard, 'arrived at a heady, impressionistic hybrid of pastoral acoustics and wraithlike feedback... Vast, wordless drones such as 'Rainstorm Blues' evoked the feeling of being a tiny human speck in a mythic English landscape, time-locked in perpetual twilight, at the mercy of the elements.' One of Simon Reynolds' blogs reproduces a 1995 article on the band where he notes that 'on their three albums and innumberable 7 inch singles so far, FSA have consistently, nay, obsessively, deployed cover images of idyllic Nature: cloud-castles in the sky, scintillating seascapes at sunset, lakeshore trees reflected in limpid water, ebbtide beaches at dusk. Then there's the song titles: "Land Beyond The Sun", "In The Light Of Time", "To The Shore", "Standing Stone", "November Mist", "Oceans"...' However, FSA's Dave Pearce punctures any grand ideas about this: "the pastoralism comes down to the fact that as a child I used to live in the countryside, in the Cotswolds. And being a shy, quiet person, I prefer the country, 'cos you can wander off on your own. In the city you get aggro and hassle all the time."

FSA were part of a Bristol scene that included Crescent, AMP, the Third Eye Foundation and Movietone. Rachel Brook was in both FSA and Movietone, and several Movietone records had a landscape connection, like the single above, released in 1997. In 2003 Movietone recorded The Sand and the Stars at various outdoor locations. As Andy Beta says in a review for Pitchfork, 'the quintet lugged recording equipment out of their home studio and into churches and warehouses, up a cliff, and even into a bay near Land's End to capture that quality. The incidental, environmental sounds infuse with guitar, dulcimer, banjo, brushed drums, cubist bass, and the pastoral whispers of Kate Wright and Rachel Brook (who offset the brunt of early Flying Saucer Attack with a gentle serenity in her maiden days).' The Domino website quotes Kate Wright: "We found the perfect bay in which to play the music, near Land’s End. The sand shelved gently and the waves were loud even on calm days. We found a house to rent above the bay. The path down to the beach was steeper than I remembered and fairly difficult to navigate in the dark. But there were clear nights under the stars. We recorded on the beach with two microphones."

Monday, August 09, 2010

Chemical and Biological Weapons Proving Ground, Dugway, UT

There are several surveillance landscapes on show at Tate Modern at the moment - the Exposed exhibition website has some of Jonathan Olley's photographs of watchtowers built by the British Army in Northern Ireland; other examples are Sophie Ristelhueber's Fait (1992) series, providing aerial evidence of the impact of the first Gulf War, and Shai Kremer's Panorama, Urban Warfare Training Centre, Tze'elim (2007). However, the photograph in this exhibition that most intrigued me was Trevor Paglen's Chemical and Biological Weapons Proving Ground / Dugway, UT / Distance - 42 miles / 10:51 am (2006). It is a beautiful, shimmering, nearly abstract image taken from so far away that the landscape is impossible to read. Paglen's website has an explanation of the 'limit telephotography' method used for this and similar images:

'A number of classified military bases and installations are located in some of the remotest parts of the United States, hidden deep in western deserts and buffered by dozens of miles of restricted land. Many of these sites are so remote, in fact, that there is nowhere on Earth where a civilian might be able to see them with an unaided eye. In order to produce images of these remote and hidden landscapes, therefore, some unorthodox viewing and imaging techniques are required. Limit-telephotography involves photographing landscapes that cannot be seen with the unaided eye. The technique employs high powered telescopes whose focal lengths range between 1300mm and 7000mm. At this level of magnification, hidden aspects of the landscape become apparent.'

Bryan Finoki's 2005 article on Paglen's work for Archinect explains that 'by zooming in on the military taking cover in the sheer remoteness of nature, Paglen seeks to debunk the mythologies that adorn the American frontier, and expose those off-limit landscapes-as-camouflage for the pervasive culture of inscrutability they serve.' Paglen is both artist and geographer, and he sees his experimental geography as running counter to the history and current practice of the discipline (he tells Finoki "I've heard that around 40% of professional geographers in this country work for the CIA or other intelligence agencies.") In the clip below he compares nineteenth century photographers, whose work helped open up the West for expansion, to modern reconnaissance satellites. In The Other Night Sky, Paglen uses the data of amateur satellite watchers to track classified spacecraft in Earth's orbit so as to photograph them over iconic Western landscapes. His book Invisible: Covert Operations and Classified Landscapes will be available soon, with an accompanying essay by Rebecca Solnit.

'A number of classified military bases and installations are located in some of the remotest parts of the United States, hidden deep in western deserts and buffered by dozens of miles of restricted land. Many of these sites are so remote, in fact, that there is nowhere on Earth where a civilian might be able to see them with an unaided eye. In order to produce images of these remote and hidden landscapes, therefore, some unorthodox viewing and imaging techniques are required. Limit-telephotography involves photographing landscapes that cannot be seen with the unaided eye. The technique employs high powered telescopes whose focal lengths range between 1300mm and 7000mm. At this level of magnification, hidden aspects of the landscape become apparent.'

Bryan Finoki's 2005 article on Paglen's work for Archinect explains that 'by zooming in on the military taking cover in the sheer remoteness of nature, Paglen seeks to debunk the mythologies that adorn the American frontier, and expose those off-limit landscapes-as-camouflage for the pervasive culture of inscrutability they serve.' Paglen is both artist and geographer, and he sees his experimental geography as running counter to the history and current practice of the discipline (he tells Finoki "I've heard that around 40% of professional geographers in this country work for the CIA or other intelligence agencies.") In the clip below he compares nineteenth century photographers, whose work helped open up the West for expansion, to modern reconnaissance satellites. In The Other Night Sky, Paglen uses the data of amateur satellite watchers to track classified spacecraft in Earth's orbit so as to photograph them over iconic Western landscapes. His book Invisible: Covert Operations and Classified Landscapes will be available soon, with an accompanying essay by Rebecca Solnit.

Sunday, August 08, 2010

Chiswick House Garden

Chiswick House, designed by the third Earl of Burlington,

completed by 1729

My photograph, July 2010

Last month we visited Chiswick House and its gardens for the first time in years, lured by the website which says: 'in recent decades the gardens fell into decline with over one million visits every year taking their toll. This decline has now been spectacularly reversed with an ambitious £12.1 million project which has restored the gardens to their original 18th century glory.' There is a nice new cafe and children's play area, but anyone thinking of going may wish to wait until the restoration is complete - the Ionic Temple for example is still under scaffolding.

The Ionic Temple and Orange Tree Garden, c. 1726

Source: Wikimedia Commons, photograph from 2008.

The restorers have erected several notices around the gardens in the form of picture frames. The one shown below reproduces an idealised view of the house and invites you to compare it with the present view (somewhat obscured by trees).

Picturesque viewpoint, Chiswick House

My photograph, July 2010

The gardens designed by Burlington and William Kent have a special place in landscape history, having inspired Alexander Pope's fourth 'Epistle' on good taste, which argues that all should be 'adapted to the genius and use of the place, and the beauties not forced into it, but resulting from it.' Here are the lines relating to garden design:

To build, to plant, whatever you intend,

To rear the column, or the arch to bend,

To swell the terrace, or to sink the grot;

In all, let Nature never be forgot.

But treat the goddess like a modest fair,

Nor overdress, nor leave her wholly bare;

Let not each beauty ev'rywhere be spied,

Where half the skill is decently to hide.

He gains all points, who pleasingly confounds,

Surprises, varies, and conceals the bounds.

Consult the genius of the place in all;

That tells the waters or to rise, or fall;

Or helps th' ambitious hill the heav'ns to scale,

Or scoops in circling theatres the vale;

Calls in the country, catches opening glades,

Joins willing woods, and varies shades from shades,

Now breaks, or now directs, th' intending lines;

Paints as you plant, and, as you work, designs.

- Alexander Pope, 'Epistle to Burlington', 1731

The cascade, Chiswick House garden, designed by William Kent

My photograph, July 2010

My photograph, July 2010

As this verse implies, the garden is both formal and informal. It has geometrical features like the Patte d’oie (‘goose-foot’) - three radiating avenues ending in small buildings - but it also has a lake created from a stream and 'naturalised'. The overall design 'pleasingly confounds, surprises, varies'. As John Dixon Hunt says in The Figure in the Landscape (p96), the visitor, once walking down the main axis of the garden, was confronted with 'frequent openings that tempted to left and right; once such invitations to divert from the main avenue were accepted the windings and intricacies of the garden were quickly discovered.'

Jean Rocque, Plan du Jardin & Vue des Maisons de Chiswick, 1736

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Finally, here are The Beatles in May 1966 performing 'Paperback Writer' in the gardens. At the start you can see them at the exedra, a semicircular yew hedge which formed a backdrop to Burlington's copies of antique statues said to represent Caesar, Pompey and Cicero. The other main location is the conservatory, renowned for its camellias, designed by Samuel Ware in 1813, a forerunner of the famous glasshouses at Kew and Crystal Palace.

Labels:

Alexander Pope,

gardens,

viewing points

Location:

Chiswick House, London

Sunday, August 01, 2010

Lu Mountain's true face

Mount Lu

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Lu Mountain (Lu-shan or Hermitage Mountain), at the juncture of the Long River and Lake P'o-yang in China, must be a contender for the most inspirational landscape in literature. It became established as an important religious centre with the arrival of Hui-yung (332-414), for whom the West-Forest Monastery was rebuilt in 377, and Hui Yüan (334-416) who taught Pure Land Buddhism at the East-Forest Monastery. The poet T'ao Yüan-ming (365-427), founder of the fields-and-gardens tradition (see my earlier post here) knew Hui Yüan and lived on a farm near the mountain. Hsieh Ling-yün (385-433), whose mountains-and-rivers poetry I discussed here earlier, was influenced by the teachings of Hui Yüan and wrote about Lu-shan, with its 'jumbled canyons', 'thronging peaks' and 'dragon pools.'

Three hundred years later the T’ang Dynasty poet Meng Hao-jan (689-740) had his own mountain home further west in Hsiang-yang and made Deer-Gate Mountain there famous through his poetry. But on one of the many journeys he made as an official he wrote about Incense Burner Peak, the most spectacular in the Lu Mountain range, and the distant sound of the bell from East-Forest monastery. Li Po (701-62) stayed at the monastery and wrote of the silence and emptiness that could be found there away from the city. Climbing towards Incense-Burner Peak, he gazed at the waterfall, three thousand feet high, and wrote a celebrated poem which I have discussed here previously.

Po Chü-i (772-848) composed poems about the mountain and a famous prose account of the thatch hut he built in 817 facing Incense-Burner’s north slope. From this place he could experience 'the blossoms of Brocade Valley' in spring, 'in summer the clouds of Stone Gate Ravine, in autumn the moon over Tiger Creek, in winter the snows on Incense Burner Peak' (trans. Burton Watson). I particularly like his description of the way water was channeled around the hut, with a small waterfall that in twilight and dawn had 'the color of white silk' and at night made 'a sound like jade pendants or a lute or harp' A bamboo trough led water from a spring in the cliff, across the hall into channels that fell from the eaves to wet the paving, giving 'a steady stream of strung pearls, a gentle mist like rain or dew, dripping down and soaking things or blowing far off in the wind.'

By the Sung Dynasty, the mountain was almost overburdened with poetic tradition. In An Anthology of Chinese Literature Stephen Owen writes that Su Tung p’o (Su Shi, 1037-1101) resolved to visit the mountain as 'an "innocent traveler", wanting to experience the mountains without writing poems (as a modern tourist might resolve to travel without taking photographs).' But he was unable to restrain himself and ended up composing several, writing his own reputation into the landscape with perhaps the best known of all the mountain's poems, a quatrain 'Inscribed on the Wall of West Forest Monastery', stating the impossibility of ever knowing Lu Mountain's true face.

Labels:

Hsieh Ling-yün,

huts,

Li Po,

Meng Hao-jan,

mountains,

Po Chü-i,

Su Shi,

T'ao Yüan-ming

Location:

Lushan National Forest Park

Saturday, July 31, 2010

Where flowers drop and waters flow

Shen Fu's memoir, Six Records of a Floating Life (1809), describes his life as an undistinguished civil servant and art enthusiast, with an account of some of the famous landscapes seen on his travels. The book's popularity has rested on the poignant account Shen Fu gives of his marriage to Yün, with their shared interests and misfortunes from the age of thirteen, when their marriage was arranged, to Yün's death at the age of forty. Here is an incident from a section on 'The Pleasures of Leisure' in which the two of them make a a miniature landscape in a rectangular pot:

'The mountain was on the left, with another small mound on the right. Along the mountain we made horizontal patterns, similar to those on the mountain paintings by Yün-lin. The cliffs were irregular, like those along a river bank. We filled an empty corner of the pot with river mud and planted duckweed, white with many petals. On top of the stones we planted morning glories, which are usually called cloud pines. It took us several days to complete. By the deep autumn the morning glories had grown all over the mountain, covering it like wisteria hanging from a rock face, and when their flowers bloomed they were a deep red. The white duckweed also bloomed, and letting one's spirit wander among the red and white was like a visit to Peng Island. We put the pot under the eaves and discussed it in detail: here we would build a pavilion on the water, there a thatched arbour; here we should inscribe a stone with the characters 'Where flowers drop and waters flow'. We could live here, we could fish there, from this other place we could gaze off into the distance. We were as excited about it as if we were actually going to move those imaginary hills and vales. But one night some miserable cats fighting over something to eat fell from the eaves, smashing the pot in an instant.' (Trans. Leonard Pratt and Chiang Su-hui)

'The mountain was on the left, with another small mound on the right. Along the mountain we made horizontal patterns, similar to those on the mountain paintings by Yün-lin. The cliffs were irregular, like those along a river bank. We filled an empty corner of the pot with river mud and planted duckweed, white with many petals. On top of the stones we planted morning glories, which are usually called cloud pines. It took us several days to complete. By the deep autumn the morning glories had grown all over the mountain, covering it like wisteria hanging from a rock face, and when their flowers bloomed they were a deep red. The white duckweed also bloomed, and letting one's spirit wander among the red and white was like a visit to Peng Island. We put the pot under the eaves and discussed it in detail: here we would build a pavilion on the water, there a thatched arbour; here we should inscribe a stone with the characters 'Where flowers drop and waters flow'. We could live here, we could fish there, from this other place we could gaze off into the distance. We were as excited about it as if we were actually going to move those imaginary hills and vales. But one night some miserable cats fighting over something to eat fell from the eaves, smashing the pot in an instant.' (Trans. Leonard Pratt and Chiang Su-hui)

Ni Zan (also known as Yün-lin),

Woods and Valleys of Mount Yu, 1372

Woods and Valleys of Mount Yu, 1372

Location:

Suzhou, where Shen Fu lived

Thursday, July 29, 2010

The lush blue landscape

Last year Denis Dutton, editor of that useful website Arts and Letters Daily, published The Art Instinct, a book that applies evolutionary thinking to aesthetics. Of particular interest for this blog is his opening chapter, 'Landscape and Longing', which begins with a discussion of Komar and Melamid's America's Most Wanted, a project I briefly discussed here before (one of the comments made on that post was a recommendation to read The Art Instinct). Dutton takes Komar and Melamid's survey seriously and argues that 'the lush blue landscape type that the Russian artists discovered is found across the world because it is an innate preference.' To do this he draws on some of the psychology of landscape literature that has grown up in the wake of Jay Appleton's book The Experience of Landscape:

This painting is reproduced in The Art Instinct.

Dutton says of it: 'the worldwide attraction of such landscapes even today is very likely an evolved trait'

Well, inspired by this line of research I tested my own six year old son with some art postcards. He wasn't terrifically excited by any of them and certainly showed little interest in my example of a 'lush blue landscape' - his favourite was a forbidding vista of ice and mountains by Caspar Wolf. Not to be put off, I then decided to search for atavistic environmental preferences in my wife, only to be disappointed when she picked out Friedrich's nearly featureless and abstract Monk by the Sea. However, she then went on to say that she also liked a Cezanne and a Klimt because they had beautiful trees. And asked about the lush blue landscape (by Claude) she said "yes I guess that's got trees too but, I don't know, there's something too big and spacious about that landscape..."

The Art Instinct has provoked a lot of debate and commentary (for example on the website of the The International Cognition & Culture Institute). Denis Dutton assures readers and reviewers that he is not being reductive and views art as much more than just a product of evolution. He covers a lot of ground and writes engagingly, but a fuller discussion on landscape might have helped to dispel natural concerns that the arguments being made are insufficiently sophisticated. A longer treatment could have explored in more detail the relationship between research into our attitudes to certain natural environments and the slow development and complex history of landscape art in different parts of the world. The book could also have dealt with more of the literature on landscape preferences, which is referred to in one of the articles collected on Dutton's website, a review by Mara Miller (author of The Garden as an Art).

Miller writes that 'there is no mention of the recent work on palaeolithic art, like David Lewis-Williams’s The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art (Thames and Hudson, 2004), or theory about the selective advantage conferred by Stone Age campsite selection. More troublesome, Dutton does not mention, much less analyze (nor even cite in the bibliography), the deep body of work by new philosophers over the past fifteen years that is directly relevant to his topics and arguments.' She goes on to list Emily Brady’s Aesthetics of the Natural Environment (University of Alabama Press, 2003), Malcolm Budd’s The Aesthetic Appreciation of Nature (Oxford University Press, 2002), The Aesthetics of Human Environments, edited by Arnold Berleant and Allen Carlson (Broadview Press, 2007); and the essays in The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism's “Special Issue on Environmental Aesthetics” 56 (1998), 'with John Andrew Fisher’s “What the Hills Are Alive With: In Defense of the Sounds of Nature” (this last highly relevant, given Dutton’s relatively extensive discussion of sound and music).' Some useful references there if you're interested in this topic.

- Gordon H. Orians and Judith H. Heerwagen in 'Evolved Responses to Landscapes' (1992) suggest human beings would take pleasure in 'savanna landscapes', featuring open spaces with low grass and groupings of trees, with evidence of water, diverse vegetation, animal and bird life, and a view to the horizon. Our taste in trees depends on how climbable they are: the authors posit a cross-cultural preference for dense canopies that fork near the ground.

- Stephen and Rachel Kaplan (e.g. Cognition and Envionment, 1982) have looked at the degree of complexity people like in landscapes and found a tendency to prefer terrain that both 'provides orientation and invites exploration.' Legibility is enhanced with a clear focal point, whilst rivers or paths leading out of a picture give a pleasurable sense of mystery.

- Jay Appleton's original 'prospect and refuge' idea suggested that humans prefer to view a prospect from a place of refuge, ideally with an overhang (e.g. trees or roof) and protection from behind.

- Steve Sailor's 2005 article, 'From Bauhaus to Golf Course' describes this earlier literature and makes the link to Komar and Melamid's America's Most Wanted. Sailor says that 'Harvard biologist Edward O. Wilson, author of the landmark 1975 book Sociobiology, once told me, "I believe that the reason that people find well-landscaped golf courses 'beautiful' is that they look like savannas, down to the scattered trees, copses, and lakes, and most especially if they have vistas of the sea."'

- J.D. Balling and J.H. Falk ('Development of Visual Preference for Natural Environments', 1982) showed photographs of landscapes to six different age groups and found a preference among the youngest: eight year olds preferred savannas to forests and deserts. Similar results have apparently been found by Erich Synek and Karl Grammer (no precise reference for this research is given by Dutton). They believe that increasing outdoor experience develops children's sophistication in response to landscapes.

- Finally, moving from age to gender, Dutton cites Elizabeth Lyons ('Demographic Correlates of Landscape Preference', 1983) who has found that women have a greater liking for vegetation in landscapes than men, with an evolutionary predisposition towards areas providing refuge and fruit, as opposed to prospects providing opportunities for exploration and hunting.

Frederick Edwin Church, The Heart of the Andes, 1859

Source: Wikimedia Commons

This painting is reproduced in The Art Instinct.

Dutton says of it: 'the worldwide attraction of such landscapes even today is very likely an evolved trait'

Well, inspired by this line of research I tested my own six year old son with some art postcards. He wasn't terrifically excited by any of them and certainly showed little interest in my example of a 'lush blue landscape' - his favourite was a forbidding vista of ice and mountains by Caspar Wolf. Not to be put off, I then decided to search for atavistic environmental preferences in my wife, only to be disappointed when she picked out Friedrich's nearly featureless and abstract Monk by the Sea. However, she then went on to say that she also liked a Cezanne and a Klimt because they had beautiful trees. And asked about the lush blue landscape (by Claude) she said "yes I guess that's got trees too but, I don't know, there's something too big and spacious about that landscape..."

The Art Instinct has provoked a lot of debate and commentary (for example on the website of the The International Cognition & Culture Institute). Denis Dutton assures readers and reviewers that he is not being reductive and views art as much more than just a product of evolution. He covers a lot of ground and writes engagingly, but a fuller discussion on landscape might have helped to dispel natural concerns that the arguments being made are insufficiently sophisticated. A longer treatment could have explored in more detail the relationship between research into our attitudes to certain natural environments and the slow development and complex history of landscape art in different parts of the world. The book could also have dealt with more of the literature on landscape preferences, which is referred to in one of the articles collected on Dutton's website, a review by Mara Miller (author of The Garden as an Art).

Miller writes that 'there is no mention of the recent work on palaeolithic art, like David Lewis-Williams’s The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art (Thames and Hudson, 2004), or theory about the selective advantage conferred by Stone Age campsite selection. More troublesome, Dutton does not mention, much less analyze (nor even cite in the bibliography), the deep body of work by new philosophers over the past fifteen years that is directly relevant to his topics and arguments.' She goes on to list Emily Brady’s Aesthetics of the Natural Environment (University of Alabama Press, 2003), Malcolm Budd’s The Aesthetic Appreciation of Nature (Oxford University Press, 2002), The Aesthetics of Human Environments, edited by Arnold Berleant and Allen Carlson (Broadview Press, 2007); and the essays in The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism's “Special Issue on Environmental Aesthetics” 56 (1998), 'with John Andrew Fisher’s “What the Hills Are Alive With: In Defense of the Sounds of Nature” (this last highly relevant, given Dutton’s relatively extensive discussion of sound and music).' Some useful references there if you're interested in this topic.

Labels:

Frederic Edwin Church

Location:

Chimborazo, Ecuador

Friday, July 23, 2010

The Road North

When Basho and Sora set off in 1689 on the Narrow Road to the Deep North, they were traveling into the past, to re-visit landscapes with long held poetic associations. As Haruo Shirane says in Traces of Dreams: Landscape, Cultural Memory and the Poetry of Basho, these places (utamakura) had traditionally served as 'cultural nodes in the poetic tradition', where travelers could hope to compose poems that would match the famous examples of their predecessors. Shirakawa Barrier for example, features in a tenth century poem by Taira Kanemori and is then treated by Priest Noin in 1025, by Minamoto Yorimosa in 1170, and by later poets like Saigyo and Sogi (whose account of his journey to the Shirakawa Barrier in 1468 is a precursor of The Narrow Road to the Deep North). Interestingly Basho seems to have been more easily inspired to compose haikai where an utamakura disappoints his expectations - at Shinobu Mottling Rock, for example, where he and Sora find the renowned rock lying face down, half buried in the grass. And as he made his way north Basho established new haimakura, haikai places that do not appear in the work of earlier poets like Saigyo and Sogi. As Basho's follower Kyoriku wrote, "travel is the flower of haikai. Haikai is the spirit of the traveler. Everything that Saigyo and Sogi have overlooked is haikai.'

A new sequence of hamaikura is now being established in Scotland by artist-poets Alec Finlay and Ken Cockburn, who are making their own journey inspired by Basho and Sora. As their blog The Road North explains, they are creating a word-map 'as they travel through their homeland, guided by the Japanese poet Basho, whose Oku-no-Hosomichi (Narrow Road to the Deep North) is one of the masterpieces of travel literature. Ken and Alec left Edo (Edinburgh) on May 16, 2010 – the very same date that Basho and his companion Sora departed in 1689 – and when they return, on May 16, 2011, they will publish 53 collaborative audio and visual poems describing the landscapes they have seen and people they have met.' So far they have reached seven of the stations on Basho's journey - Scotland's equivalent of the rock at Shinobu and Shirakawa Barrier lie ahead (see map). Nor have they yet got to a version of Nikko where, as I mentioned in an earlier post, I once made my own literary pilgrimage to see a station on Basho's journey north. A few days ago they were at their Cascade of Silver Threads (Shiraito-no-taki) - the Falls of Bruar - and there, like Japanese poets, they were conscious of their own poetic predecessors, in this case Robert Burns, who wrote about the Falls in 1787:

Here, foaming down the skelvy rocks,

In twisting strength I rin;

There, high my boiling torrent smokes,

Wild-roaring o'er a linn:

Enjoying each large spring and well,

As Nature gave them me,

I am, altho' I say't mysel',

Worth gaun a mile to see.

from 'The Humble Petition of Bruar Water'

A new sequence of hamaikura is now being established in Scotland by artist-poets Alec Finlay and Ken Cockburn, who are making their own journey inspired by Basho and Sora. As their blog The Road North explains, they are creating a word-map 'as they travel through their homeland, guided by the Japanese poet Basho, whose Oku-no-Hosomichi (Narrow Road to the Deep North) is one of the masterpieces of travel literature. Ken and Alec left Edo (Edinburgh) on May 16, 2010 – the very same date that Basho and his companion Sora departed in 1689 – and when they return, on May 16, 2011, they will publish 53 collaborative audio and visual poems describing the landscapes they have seen and people they have met.' So far they have reached seven of the stations on Basho's journey - Scotland's equivalent of the rock at Shinobu and Shirakawa Barrier lie ahead (see map). Nor have they yet got to a version of Nikko where, as I mentioned in an earlier post, I once made my own literary pilgrimage to see a station on Basho's journey north. A few days ago they were at their Cascade of Silver Threads (Shiraito-no-taki) - the Falls of Bruar - and there, like Japanese poets, they were conscious of their own poetic predecessors, in this case Robert Burns, who wrote about the Falls in 1787:

Here, foaming down the skelvy rocks,

In twisting strength I rin;

There, high my boiling torrent smokes,

Wild-roaring o'er a linn:

Enjoying each large spring and well,

As Nature gave them me,

I am, altho' I say't mysel',

Worth gaun a mile to see.

from 'The Humble Petition of Bruar Water'

Saturday, July 17, 2010

And all the peaks shone

The Present Order is the Disorder of the Future - Saint-Just

Sculpture at Ian Hamilton Finlay's Little Sparta

Source: Wikimedia Commons

On Thursday I went to the National Theatre to see a new version of Danton's Death, Georg Büchner's extraordinary first play - written when he was twenty-one, only two years before his early death from typhus in 1837. The writing is so vivid that you're swept along - I almost found myself cheering a terrifying speech by Saint-Just, and I thought of Ian Hamilton Finlay's interest in this Apollonian figure, whose life was cut short by the guillotine at the age of twenty-six. Anyone who admires the modernity and power of this play should also read Lenz, Büchner's account of the descent into madness of a young Sturm und Drang playwright. Lenz begins in the Vosges: 'snow on the peaks and upper slopes, down into the valleys grey stone, green patches, rocks and pine trees.' Here is an extract from the description of Lenz's journey over the mountains (found on the blog Dispatches from Zembla):

Only once or twice, when the storm forced the clouds down into the valleys and the mist rose from below, and voices echoed from the rocks, sometimes like distant thunder, sometimes in a mighty rush like wild songs in celebration of the earth; or when the clouds reared up like wildly whinnying horses and the sun's rays shone through, drawing their glittering sword across the snowy slopes, so that a blinding light sliced downwards from peak to valley; or when the stormwind blew the clouds down and away, tearing into them a pale blue lake of sky, until the wind abated and a humming sound like a lullaby or the ringing of the bells floated upwards from the gorges far below and from the tops of the fir trees, and a gentle red crept across the deep blue , and tiny clouds drifted past on silver wings, and all the peaks shone and glistened sharp and clear far across the landscape; at such moments he felt a tugging in his breast and he stood panting, his body leaned forward, eyes and mouth torn open; he felt as though he would have to suck up the storm and receive it within him.

Lenz walks on, increasingly lonely and fearful as darkness descends, until he eventually finds himself in the village of Waldbach where he is helped by the pastor Obelin. The rest of the narrative describes his struggles to find mental peace in this place: "you know I can't bear it anywhere but here, in this countryside; if I couldn't get out on to a mountain occasionally and see the landscape all around, then come home and walk through the garden and look inside through the window - I'd go mad!" Sadly the landscape cannot cure the mental disturbances that come with increasing frequency or the ultimate collapse where all Lenz can hear is the constant scream of silence. He is taken back to Strasbourg by carriage, from which he sees another heightened landscape, with no end to his mental torment in sight. This translation is from the really excellent John Reddick edition of Büchner's writings, published by Penguin:

Towards evening they reached the Rhine Valley. They drew further and further away from the mountains that now rose into the red of evening like a deep-blue crystal wave upon whose floods of warmth the russet glow of evening played; across the plain at the foot of the mountains lay a gossamer of shimmering blue. It grew dark as they came closer to Strasbourg; a full moon high in the sky, distant objects all dark and vague, only the hill close by in sharp relief; the earth was like a goblet of gold over which the golden waves of moonlight foamed and tumbled. Lenz stared out, impassive, without a flicker of recognition or response, except for a turbid fear that grew as more and more things disappeared in the darkness.

Labels:

Ian Hamilton Finlay,

mountains

Location:

Waldersbach, France

Friday, July 16, 2010

The tame delineation of a given spot

Henry Fuseli, who became professor of painting at the Royal Academy in 1799, famously warned his pupils off 'that kind of landscape which is entirely occupied with the tame delineation of a given spot.' Such views 'may delight the owner of the acres they enclose, the inhabitants of the spot, perhaps the antiquary or the traveller, but to every other eye they are little more than topography. The landscape of Titian, of Mola, of Salvator, of the Poussins, Claude, Rubens, Elzheimer, Rembrandt and Wilson, spurns all relation with this kind of map-work.' In the wake of artists like Constable this distinction should have seemed outmoded but, as John Barrell points out in an article inspired by the recent Paul Sandby exhibition, 'Topography v. Landscape', the contrast between mere topography and true landscape art became more important as the nineteenth century progressed.

A View of Vintners at Boxley Kent,

with Mr Whatman's Turkey Paper Mills (detail), Paul Sandby, 1794

Barrell points in his article to the influence of a series of essays by William Pyne, 'The Rise and Progress of Watercolour Painting in England' (1823-4), which traced the shift from 'tinted drawing' (of which Sandby was the chief exponent) to the modern school of watercolour painting. For Pyne, topographical images were views of ancient sites that would appeal to the antiquarian, as opposed to landscapes - rural scenes where specific buildings were secondary. Clearly modern artists like Girtin and Turner painted both kinds of view, but later writers tended to associate their approach with the word 'landscape', whilst 'topography' became synonymous with the earlier, less sophisticated style. In the nineteenth century the British Museum's collection of landscapes was split between those deemed art - filed in the Prints and Drawings collection - and a large group labeled 'topography' which was kept with maps in the library.

What did Paul Sandby's contemporaries understand by the word 'topographical' in relation to art? John Barrell has been searching the online 18th century databases, checking the years between 1751 and 1800. 'I have had, in three separate searches over a fortnight, a total of between 2000 and 3000 hits for 'topographical'. Sad I know, but that's what life is like for the semi-retired.' Sad? It sounds delightful fun, although I'm surprised there aren't students queuing up to help him. Anyway, after stripping out repetitions, Barrell reports that his pile of references was reduced down to 33: 'most of the time the adjective was used more or less as Pyne used it, in connection with images of old buildings of antiquarian interest.' This suggests a much narrower sense of the word than we would expect given the range of scenes depicted by Paul Sandby and other 'topographical' artists. As Barrell points out and the exhibition made clear, Sandby's landscape paintings are 'topographical' in the broader sense that we find in topographical writing - capable of conveying different aspects of a site's history, economy, architecture and natural features. As such they may delight the cultural geographer (as Fuseli might now put it) but should also impress any interested contemporary viewer with what Stephen Daniels describes as 'the scope and intensity of 18th-century topographical art'.

A View of Vintners at Boxley Kent,

with Mr Whatman's Turkey Paper Mills (detail), Paul Sandby, 1794

Source: Austenonly

Barrell points in his article to the influence of a series of essays by William Pyne, 'The Rise and Progress of Watercolour Painting in England' (1823-4), which traced the shift from 'tinted drawing' (of which Sandby was the chief exponent) to the modern school of watercolour painting. For Pyne, topographical images were views of ancient sites that would appeal to the antiquarian, as opposed to landscapes - rural scenes where specific buildings were secondary. Clearly modern artists like Girtin and Turner painted both kinds of view, but later writers tended to associate their approach with the word 'landscape', whilst 'topography' became synonymous with the earlier, less sophisticated style. In the nineteenth century the British Museum's collection of landscapes was split between those deemed art - filed in the Prints and Drawings collection - and a large group labeled 'topography' which was kept with maps in the library.

What did Paul Sandby's contemporaries understand by the word 'topographical' in relation to art? John Barrell has been searching the online 18th century databases, checking the years between 1751 and 1800. 'I have had, in three separate searches over a fortnight, a total of between 2000 and 3000 hits for 'topographical'. Sad I know, but that's what life is like for the semi-retired.' Sad? It sounds delightful fun, although I'm surprised there aren't students queuing up to help him. Anyway, after stripping out repetitions, Barrell reports that his pile of references was reduced down to 33: 'most of the time the adjective was used more or less as Pyne used it, in connection with images of old buildings of antiquarian interest.' This suggests a much narrower sense of the word than we would expect given the range of scenes depicted by Paul Sandby and other 'topographical' artists. As Barrell points out and the exhibition made clear, Sandby's landscape paintings are 'topographical' in the broader sense that we find in topographical writing - capable of conveying different aspects of a site's history, economy, architecture and natural features. As such they may delight the cultural geographer (as Fuseli might now put it) but should also impress any interested contemporary viewer with what Stephen Daniels describes as 'the scope and intensity of 18th-century topographical art'.

Friday, July 09, 2010

A place crowned by a single oak tree

Marcus Gheeraerts the younger, Queen Elizabeth I, c1592

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The reader of Virginia Woolf's Orlando (1928) soon realises that its hero/heroine is no ordinary person - here is the novel's fifth paragraph:

'So, after a long silence, 'I am alone', he breathed at last, opening his lips for the first time in this record. He had walked very quickly uphill through ferns and hawthorn bushes, startling deer and wild birds, to a place crowned by a single oak tree. It was very high, so high indeed that nineteen English counties could be seen beneath; and on clear days thirty or perhaps forty, if the weather was very fine. Sometimes one could see the English Channel, wave reiterating upon wave. Rivers could be seen and pleasure boats gliding on them; and galleons setting out to sea; and armadas with puffs of smoke from which came the dull thud of cannon firing; and forts on the coast; and castles among the meadows; and here a watch tower; and there a fortress; and again some vast mansion like that of Orlando's father, massed like a town in the valley circled by walls. To the east there were the spires of London and the smoke of the city; and perhaps on the very sky line, when the wind was in the right quarter, the craggy top and serrated edges of Snowdon herself showed mountainous among the clouds. For a moment Orlando stood counting, gazing, recognizing. That was his father's house; that his uncle's. His aunt owned those three great turrets among the trees there. The heath was theirs and the forest; the pheasant and the deer, the fox, the badger, and the butterfly.'

It is a fantastic view in every sense, compressing history and geography so that Snowdon, the Spanish Armada, and the city of London can all be picked out in the distance. Like Queen Elizabeth I standing on the map of England in 'The Ditchley Portrait' (above), Orlando is able to survey the whole country from beneath the oak tree. Here is an extreme version of the aristocratic prospects found in poetry and painting - Orlando gazing and counting, taking visual possession of the landscape ("the heath was theirs and the forest...") The gaze comes eventually to focus in on a butterfly, an early hint of Orlando's persistent love for the natural world (later in the book it is said that 'the English disease, a love of Nature, was inborn in her'). The symbol of the oak tree runs through the novel in the form of a poem, which Orlando works on for centuries as she observes the changes in literary fashion from Shakespeare's time to Virginia Woolf's present day. At the end of the book, Orlando thinks of burying a copy of 'The Oak Tree' but decides against it, as 'no luck ever attends these symbolical celebrations'.

'So she let her book lie unburied and dishevelled on the ground, and watched the vast view, varied like an ocean floor this evening with the sun lightening it and the shadows darkening it. There was a village with a church tower among elm trees; a grey domed manor house in a park; a spark of light burning on some glass-house; a farmyard with yellow corn stacks. The fields were marked with black tree clumps, and beyond the fields stretched long woodlands, and there was the gleam of a river, and then hills again. In the far distance Snowdon's crags broke white among the clouds; she saw the far Scottish hills and the wild tides that swirl about the Hebrides. She listened for the sound of gun-firing out at sea. No--only the wind blew. There was no war to-day. Drake had gone; Nelson had gone. 'And there', she thought, letting her eyes, which had been looking at these far distances, drop once more to the land beneath her, 'was my land once: that Castle between the downs was mine; and all that moor running almost to the sea was mine...'

In an amusing preface to Orlando, Woolf thanks all her friends and various experts - including Arthur Waley for help with the non-existent Chinese element of the book. She concludes: 'Finally, I would thank, had I not lost his name and address, a gentleman in America, who has generously and gratuitously corrected the punctuation, the botany, the entomology, the geography, and the chronology of previous works of mine and will, I hope, not spare his services on the present occasion.' I will venture to say no more about Orlando lest I provoke similar corrections from the experts - I'm very conscious of my ignorance when it comes to Virginia Woolf and others will know a lot more about this book than me (not least Mrs Plinius, who is a Woolf aficionado). However, I'll risk a few more words about the place where one might hope to find Orlando's oak tree: at Knole, the ancestral home of Vita Sackville-West.