Unknown artist, Jade Mountain Illustrating

the Gathering of Scholars at the Lanting Pavilion, 1790

Source: Wikimedia Commons

This landscape in jade shows Mount Kuaiji (in present-day Zhejiang) and the celebrated Orchard Pavilion Gathering that took place there during the Spring Purification Festival on the third day of the third month in the year 353. The event is most famous for a piece of calligraphy, the

Lantingji Xu - 'Preface to the Poems Collected from the Orchid Pavilion' written by Wang Xizhi (303-361). He describes the location, with its

'mighty mountains and towering ridges covered with lush forests and tall bamboo, where a clear stream with swirling eddies cast back a sparkling light upon both shores. From this we cut a winding channel in which to float our wine cups, and around this everyone took their appointed seats. True, we did not have harps and flutes of a great feast, but a cup of wine and a song served well enough to free our most hidden feelings.' (trans. Stephen Owen)

Feng Chengsu, Tang Dynasty copy of Wang Xizhi's Lantingji Xu (now lost)

Source: Wikimedia Commons

There were forty-two literati at this famous party and one of them was the poet Sun Chuo (Sun Ch'o, 314-71), whose

fu 'Wandering on the Tiantai Mountains' has also been translated by Stephen Owen. Here is an extract:

... I pushed through thickets, dense and concealing,

I scaled sheer escarpments looming above me.

I waded the You Creek, went straight on ahead,

left five borders behind me and fared swiftly forward.

I strode over arch of a Sky-Hung Walkway,

looked down ten thousand yards lost in its blackness;

I trod upon mosses of slippery rock,

clung to the Azure Screen that stands like a wall ...

Burton Watson has also translated this poem and writes of Sun's journey that 'as he proceeds up the mountain, the scenery becomes increasingly fantastic and idealized, until at the end he reaches a plane of pure philosophy, in which Taoist and Buddhist allusions are balanced one against the other.'

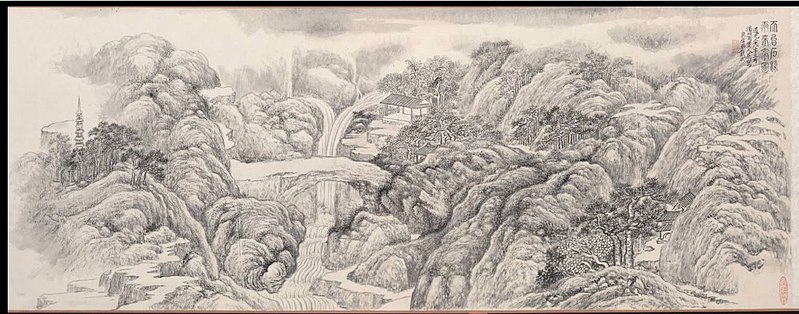

Dai Xi, Rain-coming Pavilion by the Stone Bridge at Mt. Tiantai, 1848

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Sky-Hung Walkway referred to in this poem was a natural stone bridge. It has often been depicted in art -

The Smithsonian has a twelfth century painting of it by Zhou Jichang and they describe it as follows:

'The natural rock bridge spanning a waterfall is one Tiantai's most

famous sights. According to legend, this arch is also a pathway to

paradise where the five-hundred luohan, saintly guardians of the

Buddhist faith, worship and dwell among magnificent celestial temples.

Those who venture to tread this perilous trail, however, find that the

bridge, which narrows to a width of several centimeters, is obstructed

at its far end by an insurmountable block of stone.'

There are some photographs online of tourists admiring what I assume is this same rock bridge (e.g. on

Wikimedia). In the Japanese ink painting below by

Soga Shōhaku (1730–1781) it looks much more spectacular. In this dramatic scene a mother lion throws cubs over the cliff to see which will succeed in life by being able to climb back up to her.

Soga Shōhaku, Lions at the Stone Bridge of Mount Tiantai, 1790

Source: Met Museum

An

article by Zornica Kirkova explains that Mount Tiantai also features in a poem by Sun Chuo’s friend, the Buddhist monk Zhidun (314–366). This 'opens in the idyllic setting of a spring garden, where the poet leisurely reflects on the passage of time and, “moved by things” ... lets his thoughts soar up to the sacred realm of the Celestial Terrace Mountain'.

The piping creek plays clear tunes.

Empyrean cliffs nurture numinous mists,

Divine plants, holding moisture, grow.

Cinnabar sand shimmers in the turquoise stream,

Fragrant mushrooms sparkle with the five brilliances.

In this poem, 'the mountains are envisioned as a sublime and sacred realm of purity and beauty.' As with Sun Chuo, more realistic images - the cool breeze, the clear tunes of the creek - are combined with 'fantastic paradise depictions, pertaining to the theme of immortality (eternal divine plants, cinnabar sand, magic mushrooms)'. It is easy to forget when you read poetry like this that it is a real mountain, so I will end here with an image from the internet taken with an iPhone 6S in June 2016, 1,663 years after the Orchard Pavilion Gathering.

The cliffs of Mount Tiantai