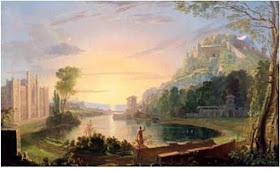

Samuel F. B. Morse, Landscape composition: Helicon and Aganippe

(allegorical landscape of New York University), 1836

This was Samuel Morse the painter, of an allegorical landscape that relocates NYU’s University Building from Washington Square to an idyllic Claudian landscape. Aganippe is a fountain at the foot of Mount Helicon dedicated to the Muses. In her book Anglophilia: Deference, Devotion, and Antebellum America, Elisa Tamarkin notes that in this painting Morse 'finds the promise of the college not in the vitality of its students and faculty (which he joined) but in the symbolic grandeur of the institution and in an organic vision that admits no sign of change but a formulaic dawn.' Such conservatism was in line with Morse's reactionary politics - he was anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant and pro-slavery. This was the kind of worldview that would influence elite American universities as they developed policies to exclude minorities.

If you are familiar with Robert Smithson's writings you can probably guess where I am going with this... 'A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey' on 30 September 1967 famously begins with Smithson purchasing a copy of the Brian W. Aldiss novel, Earthworks to read on the bus. But he also picked up a copy of that morning's New York Times and there he saw a reproduction of Morse's allegorical landscape:

'the sky was a subtle newsprint grey, and the clouds resembled sensitive stains of sweat reminiscent of a famous Yugoslav watercolourist whose name I have forgotten. A little statue with right arm held high faced a pond (or was it the sea?). “Gothic” buildings in the allegory had a faded look, while an unnecessary tree (or was it a cloud of smoke?) seemed to puff up on the left side of the landscape.'So much for Morse; Smithson makes no mention of his role in developing an entirely new form of signification and communication. Smithson got off the bus when he reached the first 'monument' of his tour, a bridge over the Passaic. He must still have been thinking about the dead landscape reproduced in the paper. As he watched the bridge open to let a barge go past, he viewed these actions as 'the limited movements of an outmoded world.'

Does the painting remind you of Claude Lorrain? Different century and different country, but have a look, for example, at Claude Lorrain's Veduta of Delphi

ReplyDeletehttps://www.wikiart.org/en/claude-lorrain/veduta-of-delphi-with-a-sacrificial-procession