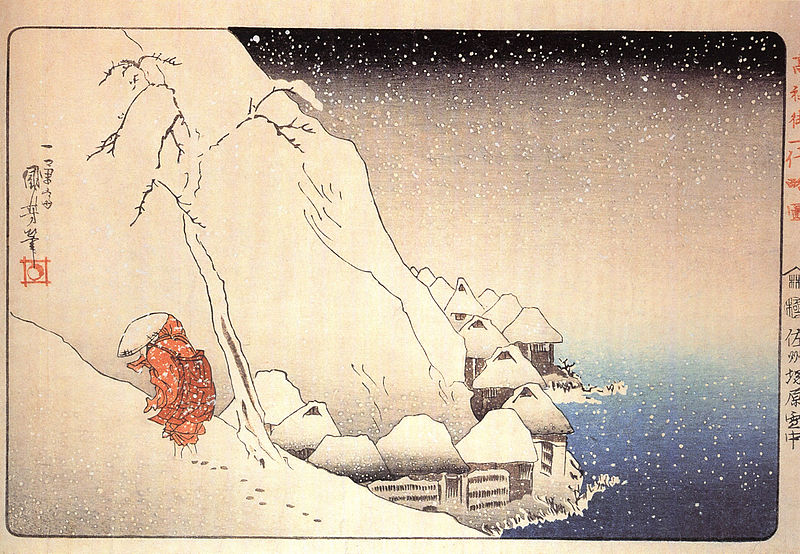

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Nichiren going into exile on the island of Sado, 1835-6

Exile has been a spur to some of the greatest literature: would we have The Divine Comedy if Dante had not had to leave Florence and learn 'the bitter taste of others' bread'? It could be said that the whole 'rivers-and-mountains' tradition in Chinese poetry stems from the exile of Hsieh Ling-yün in 422 to the wild southern coast. Literary heroes from Prince Rama to Prince Genji have found themselves sent into exile. Just recently I was looking round the National Gallery's Delacroix exhibition which includes his painting Ovid Among the Scythians. Beyond the small group coming to the aid of the poet, there is a dark, inhospitable landscape. The banishment of a writer like Ovid can evolve into a kind of legend itself, the historical facts having become lost to us. Here I want to write about the exile of Zeami Matokiyo, banished in 1434 at the advanced age of seventy-one by the shogun for reasons that are also no longer fully clear. He was sent to the island of Sado, a place that already had a long history as a place of banishment - the great Buddhist monk Nichiren, for example, was exiled there in 1271. Zeami is famous for in the West for his Noh plays and writings on aesthetics, but 'The Book of the Golden Island' (Kintosho, 1436), which describes his journey to Sado, deserves to be better known.

Arthur Waley, in his anthology The Nō Plays of Japan, wrote that Zeami's Kintosho 'bears the same relation to his plays that Basho's prose-sketches bear to his hokku.' It is shorter than Basho's travel sketches, only fourteen pages in the translation Susan Matisoff published in the Winter 1977 edition of Monumenta Nipponica, and structured in eight sections.

Jakushu: Leaving the capital, Zeami reaches the port of Obama where he looks across the bay to the mountains. He had visited this place before, many years ago, but now his memories of it are uncertain.

Sea Route: His boat sets sail across the northern sea to Sado. Far to the east, the mountain of Shirayama (now called Hakusan) is visible, wit hits lingering snow patches. Other landmarks are sighted as the boat travels day and night. Finally, he sees pine trees amid dawn waves: Sado.

Plaec of Exile: Zeami makes his way inland and stays at a small temple where water trickles through moss and the walls are damp and weathered. He looks at the moon, a lingering connection to the capital for it can be seen from there too.

Hototogisu: This section contains a story that Arthur Waley translated. The hototogisu (Japanese cuckoo) can be heard everywhere on Sado but at a certain shrine. Minister Tamekane, exiled to Sado, had composed a poem there asking the singing birds to leave because they reminded him of Kyoto.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Hototogisu, mid-nineteenth century

Images source: Wikimedia Commons

Izumi: At this place in Sado Zeami is reminded of another exile, Emperor Juntoka, whose poetry he quotes. Juntoka lived with the pure heart of a lotus and at Izumi 'must have walked the refreshing path', the road to the Pure Land paradise.

Ten Shrines: Time passes: autumn, winter, and in the spring of 1435, Zeami composes a poem to the gods of the Ten Shrines.

Northern Mountain: Zeami meets a man who tells him of this golden island's origins. Here on the highest peak the 'light of the moon of Buddha's nirvana' has shone unceasingly. Zeami comes to accept that he must live for a time this unsettled life of clouds and water.'

Firelight Ceremony: The last section of the Kintosho focuses on the traditional ceremony marking the beginning of the cycle of the seasons. It concludes with these beautiful lines:

'Look on these words,

The plover tracks

Of one left on the Golden Island,

To last as a sign, unweathered,

For future generations.'

I had always understood "hototogisu" to be a Japanese variety of cuckoo? A quick google seems to back this up.

ReplyDeleteMike

Thanks Mike - not sure why I wrote that! Now corrected.

ReplyDelete