I've been reading A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain by Daniel Defoe (3 vols, 1724-6), written whilst he was living at 'a very handsome house' just up the road from me here in Stoke Newington. It is a very handsome edition,* published by Yale University Press in 1991 and illustrated with 319 contemporary engravings and watercolours, which set me back me just £4.95 in the little second hand bookshop a few yards from the Daniel Defoe Pub. There is much I might say about it here but I want to focus on Defoe's travels in the Peak District at the beginning of Volume 3, because it reveals much about his no-nonsense attitude to landscape. The earlier volumes covering London and the South and are full of descriptions of farming, commerce and trade, thriving market towns and expanding cities. In Derbyshire he remains more fascinated with human activity and industry than the beauties of the scenery - coal and lead mining and the operation of a throwster's mill (for silk throwing), whose owner nearly came to grief once showing some friends his impressive water wheel.† And when his narrative eventually gets to the spectacular natural phenomena of The Peak, he goes out of his way to downplay them.

The first 'Wonder of the Peak' he dismisses is the baths at Buxton - 'nothing at all; nor is it any thing but what is frequent in such mountainous countries as this is, in many parts of the world.' Next, at Poole's Hole, he observes that 'the wit that has been spent upon this vault or cave in the earth, had been well enough to raise the expectation of strangers, and bring fools a great way to creep into it.' Earlier writers had gone over the top in their praise: 'Dr. Leigh spends some time in admiring the spangled roof. Cotton and Hobbes are most ridiculously and outrageously witty upon it. Dr. Leigh calls it fret work, organ, and choir work.' But 'were any part of the roof or arch of this vault to be seen by a clear light, there would be no more beauty on it than on the back of a chimney; for, in short, the stone is coarse, slimy, with the constant wet, dirty and dull.' A famous spring is 'a poor thing indeed to make a wonder of'; nor is The Devil's Arse all it has been cracked up to be (I referred to this cave here before in connection with Thomas Hobbes' book in praise of The Seven Wonders). As for Mam Tor, 'the sum of the whole wonder is this, That there is a very high hill, nay, I will add (that I may make the most of the story, and that it may appear as much like a wonder as I can) an exceeding high hill. But this in a country which is all over hills, cannot be much of a wonder, because also there are several higher hills in the Peak than that, only not just there.'

Page from The Genuine Poetical Works of Charles Cotton (1741, written 1681)

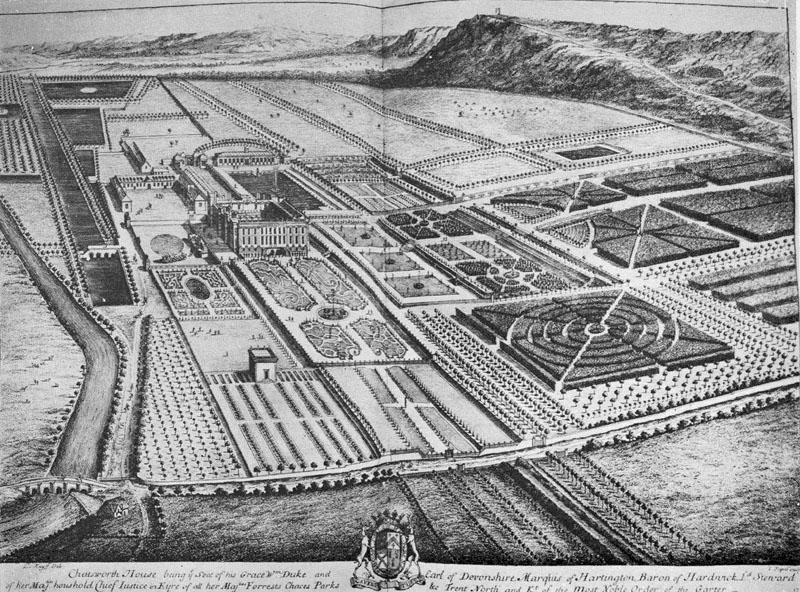

But Defoe doesn't leave the Peak District without praising two of its sights, 'one a wonder of nature, the other of art.' The extraordinary and mysterious Elden Hole is a 'frightful chasme' whose 'opening goes directly down perpendicular into the earth, and perhaps to the center. ... What Nature meant in leaving this window open into the infernal world, if the place lies that way, we cannot tell: But it must be said, there is something of horror upon the very imagination, when one does but look into it.' And then, by contrast, there is the Duke of Devonshire's house at Chatsworth, whose beautiful new garden required some serious landscaping. 'To make a clear vista or prospect beyond into the flat country, towards Hardwick, another seat of the same owner, the duke, to whom what others thought impossible, was not only made practicable, but easy, removed, and perfectly carried away a great mountain that stood in the way, and which interrupted the prospect.' The result is a house and garden that delight the traveller as a haven of civilisation in a wild place (an emotion I've always associated with Tolkien's Rivendell).

'Nothing can be more surprising of its kind, than for a stranger coming from the north, suppose from Sheffield in Yorkshire, for that is the first town of note, and wandering or labouring to pass this difficult desert country, and seeing no end of it, and almost discouraged and beaten out with the fatigue of it, (just such was our case) on a sudden the guide brings him to this precipice, where he looks down from a frightful heighth, and a comfortless, barren, and, as he thought, endless moor, into the most delightful valley, with the most pleasant garden, and most beautiful palace in the world: If contraries illustrate, and the place can admit of any illustration, it must needs add to the splendor of the situation, and to the beauty of the building, and I must say (with which I will close my short observation) if there is any wonder in Chatsworth, it is, that any man who had a genius suitable to so magnificent a design, who could lay out the plan for such a house, and had a fund to support the charge, would build it in such a place where the mountains insult the clouds, intercept the sun, and would threaten, were earthquakes frequent here, to bury the very towns, much more the house, in their ruins.'

J. Kip after L. Knyff, Birdseye View of Chatsworth House, c. 1707

* A reviewer for the London Review of Books felt this edition 'breathes an odour of ‘England’s Heritage’' and questions the way it has been abridged. Nowadays it is of course possible to read the original unabridged version online.

† 'Keeping his eye rather upon what he pointed at with his fingers than what he stept upon with his feet, he stepp'd awry and slipt into the river. He was so very close to the sluice which let the water out upon the wheel, and which was then pulled up, that tho' help was just at hand, there was no taking hold of him, till by the force of the water he was carried through, and pushed just under the large wheel, which was then going round at a great rate. The body being thus forc'd in between two of the plashers of the wheel, stopt the motion for a little while, till the water pushing hard to force its way, the plasher beyond him gave way and broke; upon which the wheel went again, and, like Jonah's whale, spewed him out, not upon dry land, but into that part they call the apron, and so to the mill-tail, where he was taken up, and received no hurt at all.'

I also have a copy of this edition and like it a lot. Some interesting observations as he travels through Fife.

ReplyDeleteThanks - this edition is a great archive of early eighteenth century pre-Romantic topographic illustration, regardless of the text. Which is what you'd expect from Yale, home of the Yale Center for British Art.

ReplyDelete