In this post I want to draw your attention to Complex Crosses, a book of close readings by my friend Edmund Hardy which 'spans the history of poetry by alighting on small fragments'. I reproduce with permission one of these in its entirety below.

Michael Drayton / compounds of place / 1622

From fast and firmer earth, whereon the Muse of late,Trod with a steady foot, now with a slower gait,Through quicksands, beach, and ooze, the Washes she must wade,Where Neptune every day doth powerfully invadeThe vast and queachy soil, with hosts of wallowing waves(Polyolbion, The Five and Twentieth Song, lines 11-15)The muse trods in gradations from the “fast and firmer” chalky uplands of Lincolnshire into the ooze of “vast and queachy soil”: “with a steady foot” begins on the chalk (to the north and south of the fens) and Jurassic rocks to the west, then down into the levels “with a slower gait” as sedimentation has slowed the landscape with “quicksands, beach, and ooze”, an interdigitation of peat, clay, silt and chalky islands. “Neptune every day” fixes the eroding action of the sea within the long time-span needed to imagine the erosion of the one-time chalk escarpment as the sea breaks in, and sedimentation fills the basin – the long span of Neptune within “every day”. The resulting fens are both sea and land, compounded linguistically in “wallowing waves”, presaging the area’s own self description in the poem “I peremptory am, large Neptune’s liquid field” (line 151). The soil is onomatopoeically queachy, heard and felt as the steady foot of the topographic muse puts a foot in, and finds that foot sucked into the landscape.

- Edmund Hardy, Complex Crosses (2014)

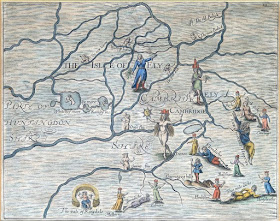

Illustration from Polyolbion (1622) engraved by William Hole

While the topographic muse trod through quicksands, beach and ooze, the inhabitants of the Fens in Drayton's day got about on stilts. Drayton mentions this in his poem and William Camden, writing a little earlier, drew particular attention to the practice. In Brittania (Latin 1586, trans 1610) we read of the inhabitants of Cambridgeshire’s peat fens: ‘a kind of people according to the nature of the place where they dwell rude, uncivill, and envious to all others whom they call Upland-men: who stalking on high upon stilts apply their mindes, to grasing, fishing and fowling.’ Isaac Casaubon spent some weeks in 1611 in and around Ely where he ‘made acquaintance with the solitary bittern and the imitative dotterel, with turf-fires and with stilts, and with the stilt walkers who were able to run so quickly. At Downham, he was surprised to see one man on stilts drive 400 cattle to pasture with the help of only one small boy.’* It is tempting to draw a comparison with Drayton's poem, which is rarely stilted but does (as I've mentioned before) tend to stride rapidly over the landscape without really touching its surface.

Drayton died in 1631 and in the subsequent decade work began on the draining of the Fens. It was a process described in a poem that has been attributed to Samuel Fortrey:

It is not surprising to read in 'An Account of Several Observables in Lincolnshire, not taken notice of in Camden, or any other Author’, written at the end of the seventeenth century by Christopher Merret, that 'Stilts are now grown out of Fashion.’I sing Floods muzled, and the Ocean tam'd,

Luxurious Rivers govern'd, and reclam'd,

Waters with Banks confin'd, as in a Gaol,

Till kinder Sluces let them go on Bail;

Streams curb'd with Dammes like Bridles, taught t'obey,

And run as strait, as if they saw their way.

* H. C. Darby, The Draining of the Fens, 1940, which contains the two quotes in the last paragraph here too.

"rarely stilted" ... i blush

ReplyDelete