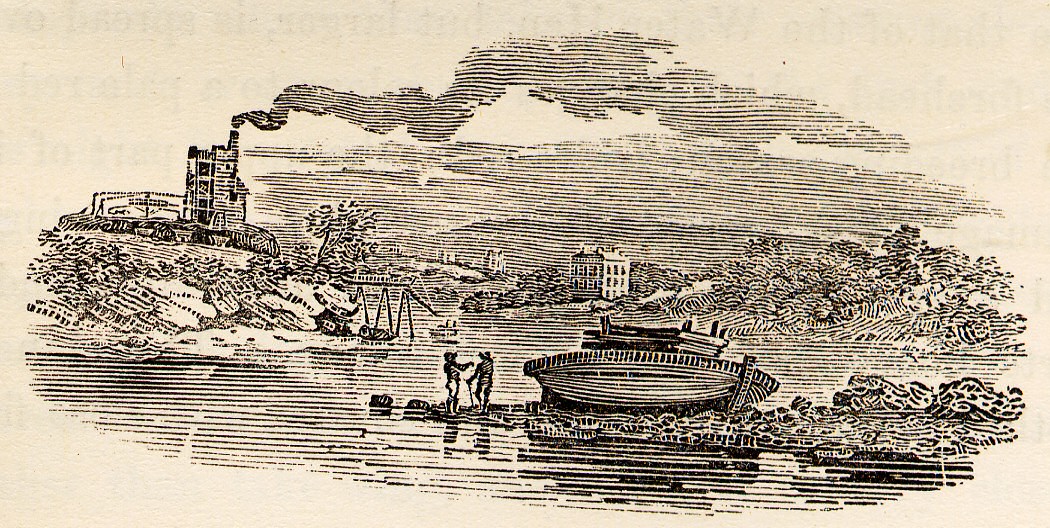

Thomas Bewick, Industry on the Riverside, 1804

'The unframed scene casts landscape into a new kind of subject. The view is not given an off-the-peg edge, independent of and indifferent to its contents. It is given a bespoke edge that responds to and defines the character of the scene.'

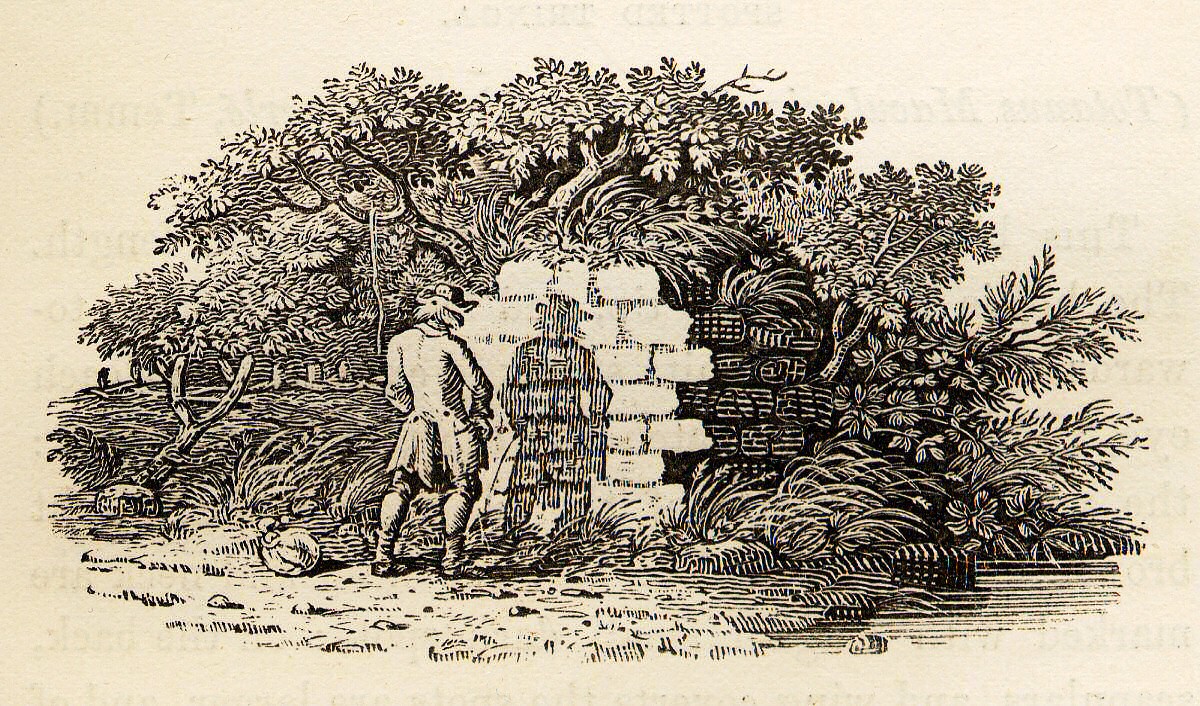

Tom Lubbock makes this interesting observation in his essay 'Defining the vignette', written to accompany a 2009 exhibition Thomas Bewick: Tale-pieces and reprinted in his posthumous collection, English Graphic. You can see in the image below of a thirsty traveller how the vignette's edges are defined by branches, leaves and tufts of grass. Lubbock saw this as 'place-portraiture', with Bewick isolating a site's distinctive features, 'those elements by which you would know it again'.

Thomas Bewick, Tail-piece - apparently of Thomas Bewick himself

as a thirsty traveller drinking from his hat, 1797

In his essay Lubbock includes a vignette of a hunter in the snow and then, underneath, the same image with a rectangular frame added. Without the frame, the snow's whiteness feels stronger, drawing into itself the whiteness of the surrounding page. Charles Rosen and Henri Zerner had previously described the way light in Bewick's landscapes 'changes imperceptibly into the paper of the book, and realises, in small, the Romantic blurring of art and reality.' Unfortunately I cannot convey the effect here because the background of the JPEG is a different white to the computer screen and thus creates its own frame.

Thomas Bewick, Hunter in the Snow, 1804

When Bewick drew something like the sea, he had no clear border to give the vignette its outline and so his lines seem to fade and blur at the edge of the image. Bewick's soft and hard edges draw attention to the ontology of perception, the distinction between things that can be delineated, like a tree, and things that cannot, like the sky. Sometimes the sky is given shading, as in the view of sea-cliffs below, and sometimes it is left blank, to give a feeling of clear open air.

Thomas Bewick, Bird's Eggs from Sea-Cliffs, 1804

Lubbock concludes his essay by drawing attention to the way vignettes differ from traditional window-like landscape views. Their figures cannot pass out of view, they are rooted in their scenes. You cannot imagine the man below ever coming to the end of his piss and walking away - if he did, he would 'start to dematerialise or break up'. (NB: this pissing figure is my example - Lubbock has a much more idyllic scene of a man on a grassy bank looking up at the sky!) Bewick's vignettes remind us how the world shrinks to what we are conscious of at a particular moment. 'They communicate what it's like to be in the middle of something, to feel things in the now, to be entirely absorbed in your sensations.'

Thomas Bewick, That Pisseth Against a Wall, 1804

All images from Wikimedia Commons