The view from Holy Island

on the morning of Maundy Thursday

Before leaving for our Easter break in Northumberland I had joked about shivering on beaches in a freezing North Sea wind. However, I hadn't appreciated how beautiful the effect of this would be, with a layer of sand swirling constantly across the surface - see my brief clip below. Watching back the video footage I took over the course of a week it sounds as if there was a constant howling gale. In one sequence on Lindisfarne I can be heard saying excitedly to the camera that the birdsong is just as you can hear it on Chris Watson's album, In St Cuthbert's Time, but none of it can be made out above the wind. It was different when we were there though, sitting among the stones on the shore, near the ruins of Lindisfarne Abbey, listening to the cry of the eider duck that is so prominent in the Lencten section of In St Cuthbert's Time. I wrote in an earlier post about hearing these recordings at Durham Cathedral in the quiet of a chapel; on Holy Island we were able to hear these sounds unmediated, carried over the water on the wind.

Earlier this month there was a short programme on the BBC called 'Into the Wind'. It followed Tim Dee as he talked of the ways the wind shapes his experiences of walking and birdwatching. An accompanying piece in the Guardian, 'The Man Who Interviewed the Wind', provoked the inevitable below the line jokes (from which I learnt the meaning of 'Dutch oven' - not a piece of landscape vocabulary that will find its way into Robert Macfarlane's word hoard), but also explains how Tim uses the natural soundscape in his work as a radio producer. 'Turning to record a little minute of the wind lets me experience the place beyond human talk. On good days, in good places, I can sense myself joined to a landscape. It is the wind that carries me there.' The programme ends with a dramatic wide-angle view of Tim pointing his microphone towards the vast mudflats of the Wash to record the wind as it surges in from the North Sea.

As Chris Watson pointed out in one of the BBC's Tweets of the Day, the sound of the eider duck is often thought to resemble that of Frankie Howerd. I found myself wondering if Cuthbert ever felt goaded by it - in Bede's Life of St Cuthbert the monks are constantly vigilant against temptation, 'our loins ever girt against the snares of the devil and all temptations'. The sounds on In St Cuthbert's Time give a peaceful impression of monastic life, but perhaps the cries of the seabirds could be a torment to monks in search of spiritual purity. 'How often have the demons tried to cast me headlong from yonder rock,' Cuthbert told visitors to his hermitage on Inner Farne. Although he was an active missionary, his life looks like a series of steps to free himself from the world. After entering the monastery of Melrose as a boy, he eventually joined the priory of Lindisfarne, easily accessible only at low tide, then isolated himself on what is now St Cuthbert's island - an islet next to Lindisfarne also regularly cut off by the sea - before leaving the priory altogether to live as a hermit on the Farne Islands. There the walls of his cell were such that all he could see was the sky, so that 'eyes and thoughts might be kept from wandering.'

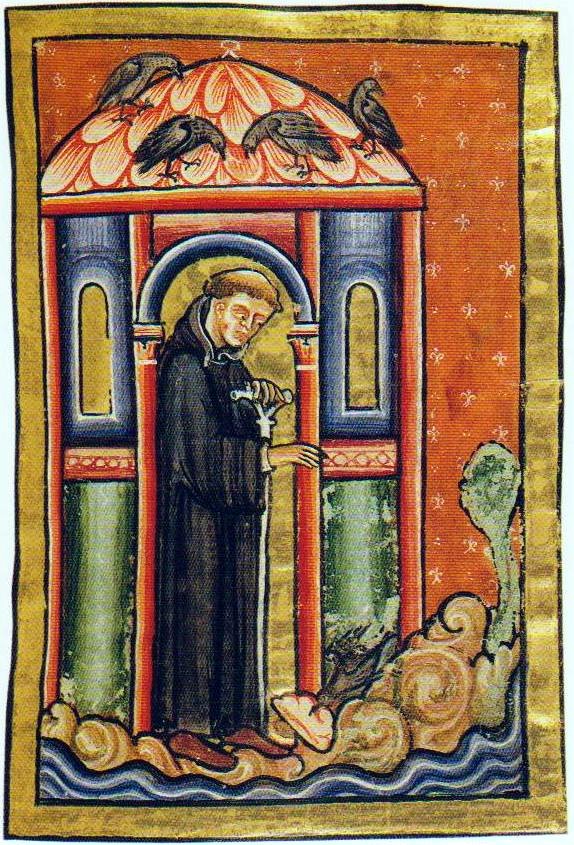

A raven brings pig's lard to Cuthbert on Farne

from the Yates Thomson MS of Bede's Life of Cuthbert, c. 1200

We took a boat trip to Inner Farne, the small island where Cuthbert lived as a hermit from 676. It is now managed as a nature reserve by the National Trust and their rangers make do with no running water ("we might smell a bit as we only shower once a week"). Cuthbert, according to Bede, found a well there with the help of God. He also persuaded the birds not to eat his crops and shamed a pair of ravens into bringing him a gift of pig's lard - incidents depicted in medieval illuminated manuscripts. Cuthbert is celebrated now for conserving the eider ducks, instituting one of the first bird protection laws. However, the language of Bede in his Life of St Cuthbert is very much about mastery over nature. In Chapter 21, Cuthbert is aided by the sea itself, which deposits with the tide a length of wood just right for his dwelling. 'It is hardly strange that the rest of creation should obey the wishes and commands of a man who has dedicated himself with complete sincerity to the Lord's service. We, on the other hand, often lose that dominion over creation which is ours by right through neglecting to serve its Creator.'

Guillemots on Inner Farne

The tide times meant that we arrived early on Lindisfarne, before anywhere was open, and so while the others ambled over the beach I tried to do some sketching. Thomas Girtin and J. M. W. Turner both came here within a year of each other at the end of the eighteenth century and drew the interior of the ruined priory. Girtin's crumbling columns were influenced by seeing the way Piranesi had depicted the ruins of Rome. Cuthbert himself must have known more Roman remnants than we see in northern Britain today; in the Life he visits Carlisle and is shown an old Roman fountain set into the city walls. Now the medieval priory, built on the site of the original one that the monks, fleeing the vikings, abandoned in 875, lies exposed to the wind. There is less of it standing than there was when Turner came here in 1797. Girtin's paintings of the priory 'emphasised the fact that it had been untouched by the hand of improvers' (Greg Smith, Thomas Girtin: The Art of Watercolour). In them, and in Turner's drawings, the ground is uneven and overgrown, very different from the green lawns maintained today by English Heritage.

J. M. W. Turner, Holy Island Cathedral, c. 1807-8

Thomas Girtin, Lindisfarne Castle, Holy Island, Northumberland, 1796-7

Lindisfarne has a castle, built in 1550, the subject of dramatic paintings by both Girtin and Turner, renovated in Arts and Crafts style by Lutyens. It is now being restored again and is inaccessible, covered in scaffold. We were able though to see nearby the little garden designed by Lutyens' friend Gertrud Jekyll, sheltered inside a dry stone wall. Before leaving the island, we walked some way round the coast, listening again to the eider ducks. We past that point where some figures can be seen in Girtin's painting, grouped around a fire. The way he shows the smoke blowing suggests the strength of the wind on the island. I will conclude here with a story in the Life of St Cuthbert that concerns wind and fire. One day, Cuthbert was staying in the home of a holy woman, who rushed in to warn him that a house in the village was alight. Cuthbert told her to keep calm and 'he went out and lay full length in front of the door. Before he had finished praying the wind had changed to the west and put the house the man of God had entered completely out of danger.' Bede concludes that God will 'give us grace, unworthy though we are, to extinguish the flames of vice in this world, and escape flames of punishment in the next.'