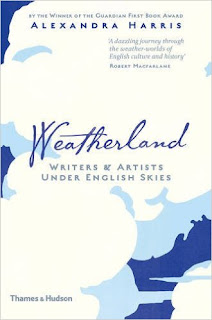

I only recently got round to reading Alexandra Harris’s Weatherland: Writers and Artists Under English Skies and can highly recommend it to readers of this blog. A book like this will cover some familiar ground – Gawain’s winter journey, Lear goading the storm, Turner’s light, Constable’s clouds, Dickens’ fog – but it is written so well that you never feel like you’re just being told things you already know. On the Wordsworths, to choose just one example, she points out that their appreciation of weather turned on ‘very specific moments of transformation – when the sun suddenly strikes through cloud, for example, or when a figure is glimpsed through fog.’ She quotes Dorothy noting ‘her favourite birch tree coming to life: “it was yielding to the gusty wind with all its tender twigs, the sun upon it and it glanced in the wind like a flying sunshine show […] It was like a spirit of water.” The earth-rooted tree takes flight in air, dissolves into a water spirit and, and glitters in the sun.’

The whole history of English literature seems to be contained in the book but it cannot of course be completely comprehensive. There is no George Eliot for instance - just as I was finishing Weatherland, Mrs Plinius was rereading Middlemarch and reminded me that the love between Will and Dorothea finally surfaces during a thunderstorm. This though is an example of ‘significant weather’, a novelist’s device deplored by Julian Barnes who, I learnt from Weatherland, originally intended his novel Metroland to be called No Weather, since he was determined to avoid using it as a symbol of anything. The book's scope is restricted to England and there are moments when Alexandra Harris comes across as very English herself (as she did in Romantic Moderns - see my post on 'The bracing glory of our clouds'). She refers, for example, to Milton’s Paradise, where the seasons are fixed and bountiful and ‘Eve lays out a spread for the visiting archangel Raphael’, observing that Eve may have been ‘the only picnicker in history to remain completely free from concerns about the weather.’ Hard to imagine, say, a Californian academic writing this!

Abraham Hondius, The Frozen Thames, 1677

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Weatherland takes inspiration at various points from Virginia Woolf's Orlando, a book I have referred to here before. My favourite scenes in Orlando concern the icing over of the Thames, when birds suddenly freeze in the air and Orlando falls in love with a Muscovite princess. Woolf herself had read an evocative account of the winter of 1608 in Thomas Dekker's The Great Frost: Cold Doings in London, which refers to a new 'pavement of glass' and fish trapped below a thick roof of ice. Here, from Weatherland's chapter 'On Freezeland Street', are three more responses to those surreal transformations of the city, which only came to an end when the demolition of London Bridge made the river swifter, deeper and permanently liquid.

- Poetry: John Taylor, Thames boatman and self-styled water-poet, composed The Cold Tearme: Or the Frozen Age: Or the Metamorphosis of the River of Thames in 1621. He compared the ice to a pastry crust and the freezing wind to a barber's razor, 'turning Thames streames, to hard congealed flakes, / And pearled water drops to Christall cakes.' He describes visitors coming to the Frost Fair, 'Some for two Pots at Tables, Cards or Dice: / Some slipping in betwixt two cakes of Ice.' Here he added a rueful note in the margin, 'Witnesse my selfe'.

- Painting: the view reproduced above is by one of the many artists who came over to England from the Low Countries in the seventeenth century. 'While Englishmen produced diagrammatic engravings of the Frost Fairs, labelling the attractions, Hondius produced an essay in atmosphere. His expansive sky, worthy of the Netherlands, is flushed with the apricot pinks of a winter sunset.' Alexandra Harris imagines the effect the frozen river would have had on his imagination. At around the same time he painted a ship stuck in the pack ice of Greenland, Arctic Adventure. 'The Thames was a noisy, busy river, but in its frozen state it transported Hondius to the desolate edges of the world.'

- Music: John Dryden may have been inspired by the Frost Fair of 1683-4 when he wrote the libretto for Purcell's King Arthur. Together 'they wanted to freeze and melt the human voice, dramatising in the process the freezing and melting of the the heart.' The evil Saxon magician Osmond strikes his wand on the ground and magically summons up 'a prospect of winter in frozen countries.' Then the personification of Cold sings slowly in C minor, chosen as the coldest key, and is followed by a chorus of cold people, whose stuttering singing mimics the chattering of teeth. The whole masque is conjured to demonstrate the warmth of love, but it is a deception played on Emmeline, who is betrothed to Arthur. His plan is foiled though and at the end of the opera he is cast into a dungeon whilst Arthur and Emmeline are reunited.

There are numerous versions of the 'Cold Song' online, some pretty strange. I've chosen here a concert version by Andreas Scholl; you can also see a video for this where the singer is dressed in a pale suit, looking lost near some tower blocks. Incidentally, the Prelude to the Frost Scene was the basis for Michael Nyman's 'Chasing Sheep is Best Left to Shepherds' in The Draughtsman's Contract and was recently used again by the Pet Shop Boys in 'Love Is a Bourgeois Construct'.