I was reading Dafydd ap Gwilym in a Welsh wood last week. Many of his nature poems were addressed to a llaitai - love-messenger - like the seagull or the skylark. As Jay Griffiths wrote in her essay, 'The Grave of Dafydd', 'he sung himself into the land, asking birds, animals and the wind to carry messages to all his well-beloveds. More yet: the now-printed words echo the print of his body on the land, as he tells of the way that the places where he made love, the crushed leaves and grass, the bed-shapes under the saplings, will remain imprinted on the landscape forever, and on the landscapes of the heart.'

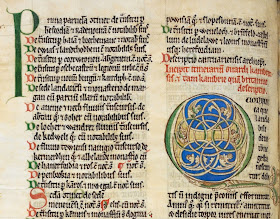

Those trysting places were not always accessible though - sometimes nature thwarted Dafydd's desires. Finding the River Dyfi in spate he composed a song in its praise in the hope that it would allow him to cross. On another day it was mist that descended just as the poet was setting out for a liaison with a slender maid. Here are some lines from the translation of Y Niwl ('The Mist') by Rachel Bromwich (from my book, pictured above, sadly no longer in print). Even in English I think they convey a vivid sense of fog on the Welsh landscape.

But there came Mist,

resembling night,

across the expanse of the

moor,

a parchment-roll, making a

black-cloth for the rain,

coming in grey ranks to

impede me

like a tin sieve that was

rusting,

a snare for birds on the

black earth,

a murky barrier on a narrow

path,

an endless coverlet to the

sky,

a grey cowl discolouring the

ground,

placing in hiding every

hollow valley,

a scaffolding that can be

seen on high,

an enormous bruise over the

hill, a vapour on the land,

a thick and pale-grey,

weakly-trailing fleece,

like smoke, a hooded cowl

upon the plain,

a hedge of rain to hinder my

good fortune,

coat-armour of the oppressive

shower.