Sara Wheeler's Terra Incognita was published twenty-one years ago, before the hundredth anniversaries of the expeditions led by Scott, Shackleton and Amundsen. Reading it recently, I wondered if we have been living through a golden age of artistic exploration, with a new series of 'firsts', as writers, filmmakers, sound artists and photographers have followed in the footsteps of the explorers and scientists, recording the environment or making site-specific work on the ice. Perhaps this pioneering period can be said to have come to an end with the first Antarctic Biennale. According to an article in Slate, 'the current plan is for the artists to construct installations in Antarctica that will be documented and removed, and then to show some of the works later in Venice. The culturati have officially reached the end of the world.'

For most of her stay in 1994-5, Sara Wheeler was hosted by the US National Science Foundation's Antarctic Artists & Writers Programme. Their website provides a fascinating insight into the range of cultural work that has taken place under its auspices. There are very few household names - the most famous is Werner Herzog, who made his enjoyable documentary Encounters at the End of the World there in 2006 (the shot of a penguin walking in the wrong direction to certain death has become famous). Herzog's musical collaborator Henry Kaiser had already been there and it was footage he had taken on his trip that persuaded Herzog to take on the project.

The list of people who preceded Sara Wheeler on the program is not long - some historians and science writers, illustrators and photographers (who must all go south highly conscious of the heroic efforts of Ponting and Hurley) and one poet, Donald Finkel, who wrote two books about Antarctica. Barry Lopez went too - the program's website lists two articles, published in 1989 and 1994, and "future book." Wheeler mentions Lopez once or twice in Terra Incognita. She recalls how Ranulph Fiennes had scoffed at the idea that the Antarctic can provide a transcendental experience: "I prayed for help there, but I would have done so in Brixton. Mr Lopez writes about it but he's hardly been there at all." Wheeler's footnote to this: 'Lopez is an established and highly respected author who has visited Antarctica five times. His trips were not exercises in seeing how dead he could get - he went to see, and to learn.'

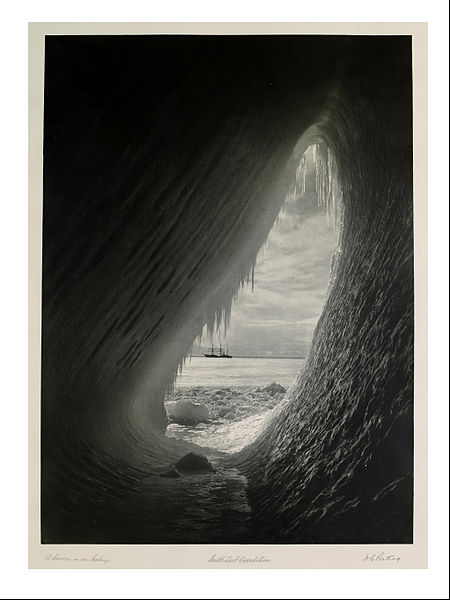

Herbert Ponting, A Cavern in an Iceberg, 1910

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Interestingly, according to the list, Kim Stanley Robinson was in Antarctica at the same time as Sara Wheeler. I rather wish they had encountered each other because she is quite amusing on cultural differences between America and Britain. Her book was conceived and written in the tradition of British travel writing (her favourite is The Road to Oxiana) whilst Robinson was researching his science fiction novel Antarctica. The one other artist she did spend time with on her second trip, which coincided with the end of the Antarctic winter, was a watercolourist called Lucia deLeiris. They shared a hut on the frozen sea and there, she writes, 'the landscape spoke to me so directly that it no longer seemed to be made of corporeal ice.'

At the end of the book, before leaving Antarctica, Wheeler returns to the Dry Valleys where she had experienced a memorable hike the previous summer. On that earlier occasion she had been visiting scientists studying Lake Fryxell, its surface 'filled with tiny white bubbles and twisted into apocalyptic configurations - a fall might land you face down on a sword reminiscent of Excalibur.' The opportunity arose to take a walk up the valley, the passing Suess and Canada Glaciers, where she noted a mummified seal on the moraine, and coming eventually to Lake Bonney, where 'ribboned crystals imprisoned in the ice glimmered like glowworms. It was swathed in light pale as an unripe lemon.' Now, months later, after the long polar night and a brief return to England, she was back.

'I knew this landscape, but I had never seen the pink glow of dawn over the Canada Glacier, or the panoply of sunset over the Suess, or in between, sunlight travelling from one peak to the next and never coming down to us on the lake. We lived in a bowl of shadow during those days. One morning the sun appeared for ten minutes in the cleft between Canada and the mountain next to it, and everyone stopped working to look up. The lake was carpeted with compacted snow, and from the middle, where the Canada came tumbling down in thick folds, the Suess was cradled by mountains like a cup of milky liquid.'

No comments:

Post a Comment