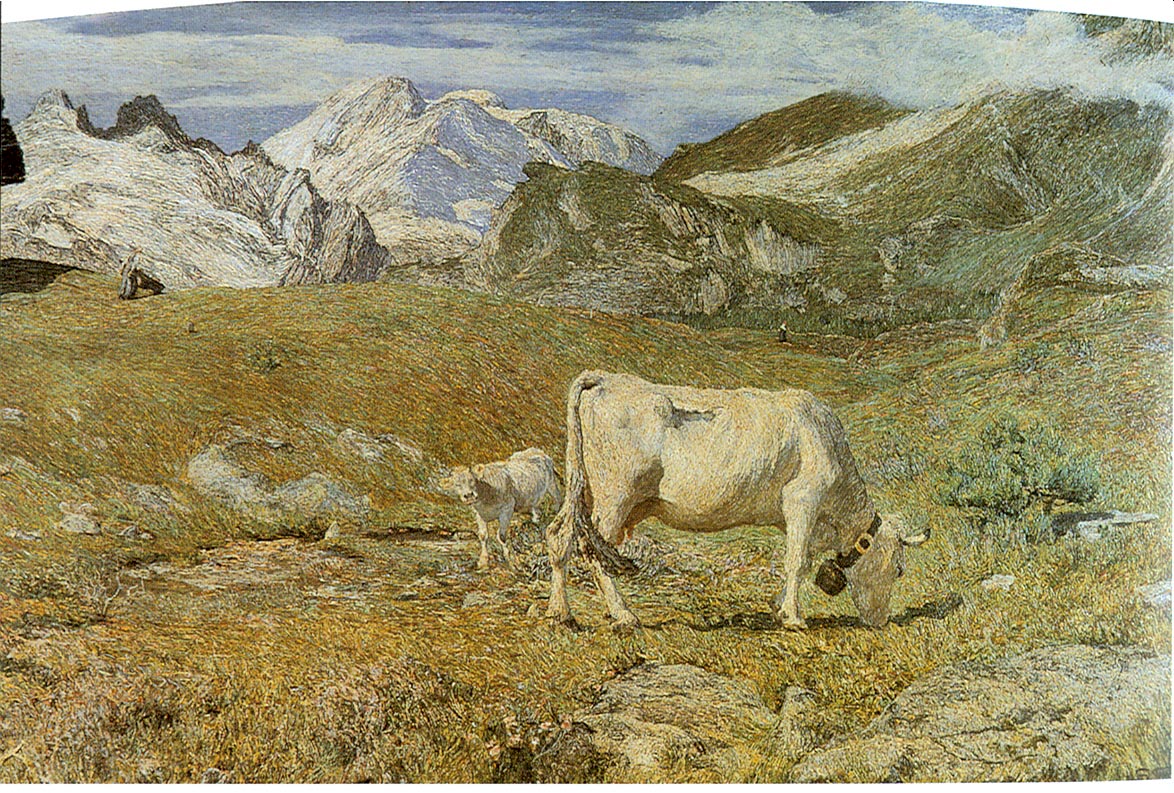

Giovanni Segantini, Spring Pastures, 1896

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Giovanni Segantini, Alpine Triptych: Death, 1898-99

Source: Wikimedia Commons

A year after Segantini's death, the Universal Exposition in Paris might have contained his extraordinary panorama of the Engadine region. In the event it was never painted, despite having initial financial support from a group of hotel owners inspired by Segantini's 'proclamation', which is quoted in Stephan Oettermann's book The Panorama: History of a Mass Medium.

Men of the Engadine!But this painted vista, stretching over 40,000 square feet, was by no means the summit of his ambition.

The project I have the honour of submitting to you, dear Engadiners and sons of the Alps, is a bold one, but as clear as the sunlight that shines on the mountains. The world knows me as a painter of Alpine scenes. My art was born amidst the solemn majesty of these peaks and here achieved the heights of its form. [...] My panorama will have nothing in common with previous products of this genre. I intend to capture this portion of the Alps on canvas, the quality of its light and the clarity of its air; I will create the perfect illusion that the observer is high in the mountains, in a green meadow, surrounded by jagged peaks and sparkling glaciers, which feed our woody slopes with never-failing streams of fresh water and lave the smiling, fruitful valleys like emeralds in the hollows....

Segantini's 1897 sketch for the rotunda to contain his panorama (Segantini Museum).

This original design echoed the architecture of the Engadine's old Alpine houses.

As the proclamation goes on to explain, visitors would enter the building through a 'gallery hewn in rock' and ascend until they emerged on a craggy prominence 50 feet high with fir trees, 'mossy stones, little bridges, streams and gorges, wild flowers and fragrant herbs'. Electrical ventilators would provide fresh air (his original idea had been to include giant ozone-producing machines) and a realistic atmosphere would be provided by lighting and hidden acoustic and hydraulic devices. Between this viewing place and the wall of the panorama Segantini pictured 'barns full of fragrant hay, grazing cattle, and various geological features as well as the most important botanical and zoological specimens of our region.' The building's facade would include symbolic representations of villages in the Upper Engadine, but also provide 28,000 square feet for advertising purposes. Oettermann concludes that the withdrawal of support for the project 'spelled the end for a project that would have resulted in the most ambitious panorama of all time, in quality as well as sheer size. It was also the death knell of the age of panoramas.'

No comments:

Post a Comment